WASHINGTON, April 8, 2015 – Dramatic growth in the craft beer sector domestically and abroad over the past five years has translated into big opportunities for American hop and barley producers who cultivate the industry’s most essential inputs.

Just in 2014, craft breweries – which by definition produce 6 million barrels of beer or less annually, or are at least 75 percent owned or controlled by a brewery of that size – sold over $19.6 billion worth of craft beer within the U.S. and $99.7 million worth in foreign markets, according to a recent study by the Brewers Association (BA).

The craft brewery share of the American beer market reached double digits recently as well, rising to 11 percent in 2014, when it was just 5 percent in 2010, according to the report.

While craft breweries cut of overall beer production seems small, farmers know that crafters use significantly higher volumes of hops (five times as much) and barley (twice as much) in their beer production than conventional breweries. For that reason, coupled with rapid increases in craft beer consumption, hops and barley farmers are taking notice.

Growth in the craft industry abroad – both in foreign craft markets that source American barley and hops and markets that import American craft beer – shows no signs of slowing either. American-style craft beer seems to have found a niche outside U.S. borders in the Pacific Rim, China, Western Europe and South America, according to the BA’s most recent export statistics released last month.

Increases in exports – a 72 percent jump in 2011 and a 36 percent increase in 2013 – wouldn’t be possible without U.S. hop farmers, said Bart Watson, the BA’s chief economist. Beer aficionados “love American style hops” and producers depend on U.S. hop farmers to deliver the quantity and quality of hops they need, he said.

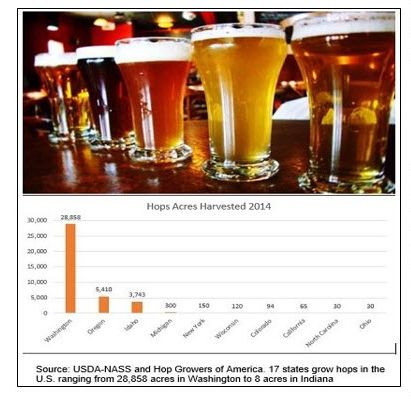

Hops are produced almost exclusively in Washington, Oregon and Idaho, on or close to the 45th parallel where the growing season temperatures are moderate and the rainfall abundant.

Ann George, a 28-year veteran of the hops industry, who represents Hop Growers of America and the Washington Hop Commission, predicted that hop growers will plant 5,000 acres more this year for several reasons, all related to the craft beer industry. Some of those new acres will be planted outside the Pacific Northwest, in Michigan and even Texas.

One reason for increasing production of hops is due to a switch in the craft beer industry’s preference for aroma hop varieties over alpha varieties, which are more bitter – “a complete flip” from 10 years ago, George said. That change is prompting hop farmers to plant new acres in hops, as aroma varieties are lower yielding than alpha, as well as more aroma varieties on existing acreage, tipping the balance between aroma and alpha crop production toward the aroma varieties.

In the past, this change in preference has created some uncertainty for hop farmers, George said. For instance, in 2007 and 2008, the industry’s demand had started to shift away from alpha varieties in favor of aroma varieties, but the hop reserves at the time were depleted, leaving craft breweries with a hops shortage.

Today, 99.9 percent of U.S. hops production is contracted, helping to mitigate the risk associated with growing the crop, which can cost as much as $18,000 per acre to cultivate, George said. Last year, just under 39,500 acres were planted in hops and about 80 million pounds were produced in the U.S.

Like hop growers, barley farmers contract production, but instead of contracting with breweries (although they do in some instances), barley farmers typically sell directly to malting facilities, because the malting process is the intermediary step that precedes brewing for barley crops. In malting, the germinated barley is immersed in water and allowed to sprout, then the grain is dried to halt the spouting. The dried grain is full of sugar, starch and a particular kind of enzyme called diastase.

Doyle Lentz, president of the National Barley Growers Association, said his organization was committed to facilitating stronger relationships with the craft brewing industry in the future to maintain stability in the barley market.

Lentz said that 80 percent or more of the 3 million acres of barley grown in the U.S. – located primarily in North Dakota, Montana, Washington and Idaho – goes into the malt market. The remaining 20 percent or so may be degraded due to poor weather or pests and is sold as animal feed for less than half the price of malt barley.

Barley requires “a lot more management” than other crops do, Lentz said. The grain is vulnerable to rain damage and a fungus called Fusarium, which causes yield-reducing head blight, and overwinters in corn, further limiting where it can be planted.

In addition, he said, “you have to be very careful with how you deal with fungicides, because it’s a non-GMO type crop, you have to use more,” and storing germinated barley for future beer production is tricky and expensive business.

[This article first appeared in our April 8, 2015 Agri-Pulse newsletter. If you aren’t a subscriber or don’t download our Wednesday newsletters, you’re missing out on stories such as this one.]

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.