WASHINGTON, June 3, 2015 – Half a million people were without clean drinking water for days – some estimates say as long as a month – in and around Toledo, Ohio, last August after a cyanobacteria algae bloom in Lake Erie rendered the area’s water toxic. Since then, city officials and other stakeholders have banded together in uncommon partnerships with Ohio and Michigan farmers – the parties who’ve shouldered the blame for the algae blooms – to control the source of the contamination and prevent another water crisis from happening this summer.

Jay Martin, a faculty member at Ohio State, told a “Toledo Water Crisis” forum audience last week that farmers, universities, and city officials were working together to minimize the nutrient load responsible for feeding the toxic algae from reaching Lake Erie.

“We need to be looking at what’s happening on the fields, all the way down to drinking water treatment plants,” he said, as farmers on the panel nodded in agreement. Such a comprehensive approach, Martin continued, starts with collaborative research and outreach efforts, like his university’s Field to Faucet Program, that works to pinpoint where and when phosphorous and nitrogen runoff from farms enters the watershed.

“We need to be looking at what’s happening on the fields, all the way down to drinking water treatment plants,” he said, as farmers on the panel nodded in agreement. Such a comprehensive approach, Martin continued, starts with collaborative research and outreach efforts, like his university’s Field to Faucet Program, that works to pinpoint where and when phosphorous and nitrogen runoff from farms enters the watershed.

These public private collaborations might seem unusual because of the tendency among some stakeholders to assign blame for the conditions. But Jack Fisher, executive vice president of the Ohio Farm Bureau, says farmers have long accepted part of the responsibility.

“The finger-pointing started among farmers themselves,” Fisher said, in the first meetings held on the algae blooms on western Ohio’s Grand Lake St. Marys, which surfaced in 2009. The row crop and livestock farmers got into blaming one another for the poor water quality, Fisher said, but after much deliberation, the farmers learned to work together despite their differences. “We’ve taken that example to the community: Let’s not point fingers, let’s figure out what needs to be done and work together,” he said.

Terry McClure, vice chair of the Ohio Soybean Council board, said farmers in Ohio have “started with the basics,” employing conservation practices like buffer strips and nutrient management plans, and are doing their part to understand exactly how much nutrient is escaping their fields by participating in university-led field edge studies.

“We have 32 sites across the state of Ohio that are doing true field edge testing, surface and sub-surface water concurrently, to understand 24/7, 365 exactly what’s leaving that farm,” he said. “From an ag perspective, it’s an all-hands-on-deck issue. So once you recognize you’re a part of the problem – and we can argue if we’re 30, 40, 50 percent (of the problem) – (but even) if you’re 30 percent of the problem, you need to be a part of the solution,” McClure said.

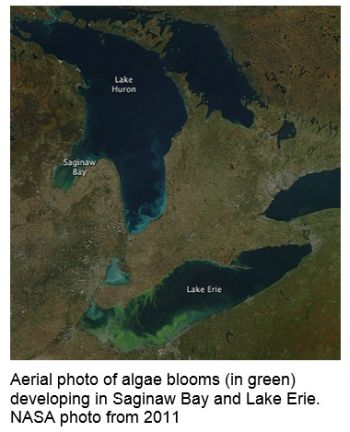

In southeast Michigan, a second unlikely couple – an agribusiness group and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a conservation non-profit – have teamed up to prevent farm-sourced nutrient and sediment pollution from ending up in Lake Huron, another of the Great Lakes.

Rich Bowman, Michigan TNC’s director of public relations, knew there “weren’t enough boots on the ground” in conservation within the Saginaw Bay Watershed to protect water quality in Saginaw Bay or Lake Huron. Jim Byrum, president of the Michigan Agri-Business Association (MABA), a long-time friend of Bowman’s, thought he might be able to help.

Together, Bowman, Byrum and their respective camps devised a private sector delivery system for conservation practices. Their project, funded with USDA Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) dollars and private investment, doesn’t depend solely on the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) like conservation initiatives have historically done. Instead, Certified Crop Advisers (CCAs) and other private industry professionals – the ones who have long enjoyed trusting and fruitful relationships with farmers in the area – are the ambassadors of conservation.

TNC and MABA enlisted the help of Michigan State University, which runs the Institute for Water Research that developed the Great Lakes Watershed Management System. Conservation ambassadors will use the system to identify the fields that are particularly vulnerable to sediment and nutrient runoff based on the individual parcel’s soil composition, slope, crop rotation and other management practices. The tool also allows the user to model how the ecological benefit of different types of conservation practices – for instance cover crops, no-till or reduced till and buffer strips – will have on a specific plot of land, across a farm, or even on a landscape-scale.

Farmers, armed with information and specifics about their options, can choose whether or not they would like to use conservation practices and/or enter into a cost-share contract with NRCS. CCAs may supply farmers with NRCS contracts, but they do not have any financial incentive to encourage sign-up. Instead, Bowman said, ambassadors have a big incentive and a small incentive to participate.

The small incentive is at the individual retail level, Bowman said. “If growers decide they want to do cover crops, they’re going to have to buy cover crop seeds from somebody,” and participating in the RCPP gives ambassadors the opportunity to expand their portfolios to include those seeds. “A lot of agronomy retailers are selling (the inputs) to these growers, and in many cases, they’re actually applying the nutrients” too, Bowman said.

The big incentive is for the agriculture sector at large. “Agriculture, just like any business needs a social license to continue to operate,” Bowman said. “There are a lot of folks looking at agriculture right now and saying, “we’re not sure what you’re doing is acceptable to us,’ so I think that agriculture as an industry recognizes that… (and) they’re going to have to do some things to make sure (their) environmental impacts are reasonable.”

Byrum echoed Bowman’s sentiments. “In agriculture, way too enough, we do good things, but we don’t tell anybody about it,” Byrum said. “So a major component of this program is a sub-piece that will enable us to articulate what we’re doing, to demonstrate what we’re doing, and talk about it with the general public.”

The Saginaw Bay Partnership “gets our folks engaged on conservation activities that help improve water quality,” Byrum said. “Everybody wants to do that, everybody knows it’s the right thing to do, this just provides an avenue and a direction for our CCAs and others to engage.”

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.