Editor’s note: This is the first in our seven-part in-depth editorial series where we take a long look ahead at “Farm & Food 2040.” We’ll explore the trends shaping not only production agriculture but the supply chain, food companies, exporters, and more. Part one looks at the changes ahead for U.S. U.S. farmland ownership, with an additional focus on “The Disruptors: Six trends that will shape the future structure of U.S. agriculture.”

Dig into U.S. farmland tenure to see what’s happening and what’s likely for the future, and Carson Futch’s 87-year-old dad, Alvin, is very typical.

Carson, a real estate agent specializing in farmland for Lakeland-based Saunders Real Estate in central and south Florida, says his dad was a fifth-generation farmer with no family members who wanted to farm, so he put his land into a family corporation and has rented it out for decades to another large farmland manager for growing strawberries.

It often happens, he says: “Farmers have invested in their land and in their operation all these years, so their land is where they will get their retirement money.”

Other likely trends for the years ahead:

- Across the next decade or two, expect the average ages of farmland owners to continue edging up.

- In fact, like the elder Futch, many are assigning their land in wills, family corporations or trusts and then just keeping it through their retirement years, avoiding the severe tax consequences of selling or gifting it while alive.

- Farmers will continue to be the most typical buyers of agricultural land, but their dominance will slip.

- Non-farmers will own more and more of the land – especially the rented acreage.

- Expect, as well, a continued swing, especially by mid-size and big farm operators, toward renting more acreage and owning less.

- There’ll be more women owners and operators, too, even while there are fewer farm operators overall.

- Food companies are demanding more traceability and sustainability – often without paying for the extra costs of doing so. That can make it harder for smaller and mid-size operations to maintain profitability without scaling up and making investments in new technology.

Tim Fevold, ASFMRA

How quickly will changes come?

For generations the turnover in ownership of America’s farm and ranch land has been slow and usually steady, and some experts say that pace won’t likely change much in the near future.

“I don’t anticipate a faster pace of turnover. I think it’ll be a continuation of the trend we’ve seen the last several decades,” says Timothy Fevold, president of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers.

Futch agrees. Despite the state’s repeated beatings, including hurricane havoc in fields and orchards and its awful greening disease disaster in citrus groves, “farmland is still going to be in demand,” he says, and values will continue to ratchet up, as they have been, in “coastal areas, where there is a lot of pressure for development.”

Besides, he says, “we have too good of a climate (for farmland to not be in demand),” and he says buyers continue to have endless reasons to invest in farmland there, including solar farms lately. Thus, he says, “I don’t see any drastic change” in the numbers of land sales.

Yet, the landscape for farm owners and operators could be changing faster than many have anticipated, says Brett Sciotto, CEO of Aimpoint Research, a global marketing research firm that has done extensive work analyzing current agricultural trends and identifying the “Farmer of the Future.” He’s identified six trends that could speed up structural changes in agriculture – putting a lot of pressure on farmers and traditional ag institutions. (See “The Disruptors: Six trends that will shape the future structure of U.S. agriculture,” below).

Though the pace may be undetermined, you should look for at least 370 million acres of agricultural lands to change hands in the 48 contiguous states at least once in the 10 to 20 years ending in 2034.

That’s the best calculated guess of American Farmland Trust (AFT), which focuses on the whos, whys and hows of access and ownership of agricultural lands and how to protect them. AFT analysts crunched numbers, including ages of landowners and principal farm operators and what farm owners and operators themselves told USDA they expect for their land in the upcoming five years, as reported in the Agriculture Department’s five-year censuses and the Economic Research Service’s 2014 report on land tenure and transfers.

AFT applied some actuarial logic to the data, and “the assumption was, given their ages, (owners and operators) are going to have to take some action in the next 10 to 20 years,” said Jennifer Dempsey, director of AFT’s Farmland Information Center. Or transfers may happen after they’re gone, and thus her center projected ownership of 40 percent of the 48 states’ 991 million farm and ranch acres will change hands from 2015 to about 2035.

AFT applied some actuarial logic to the data, and “the assumption was, given their ages, (owners and operators) are going to have to take some action in the next 10 to 20 years,” said Jennifer Dempsey, director of AFT’s Farmland Information Center. Or transfers may happen after they’re gone, and thus her center projected ownership of 40 percent of the 48 states’ 991 million farm and ranch acres will change hands from 2015 to about 2035.

Annually, farmland transfers will average only about 2 percent of all U.S. farmland, says AFT. Further, among the acres to be transferred, the majority are likely to change hands via private transactions such as gifts, wills, or trusts, and another 14 percent to be sold between family members. So, AFT says that leaves only about 25 percent being sold in any open market fashion, which translates to well under 1 percent of all U.S. farmland.

Meanwhile, Randy Dickhut, senior vice president for real estate operations at Omaha-based Farmers National Company, observes that the 1 percent per year of farmland reaching the market is now bumping up against “a large generational transfer of wealth” – the mountain of assets such as farmland accumulated by the World War II and Korean War generations.

Randy Dickhut, Farmers National

“Most people who own farmland have had it for a while,” he said, and tend to hold onto it. About 70 percent of the clients for whom Farmers National manages farmland consider family legacy a top reason to keep their land, and such clients tend to be large landowners, he said.

In similar fashion, Iowa State University’s extensive Iowa Farmland Ownership and Tenure Survey 1982-2017, recently released, says 29 percent of all Iowa landowners say that “family or sentimental reasons,” is “very important” to their land ownership – compared with 22 percent in ISU’s 2012 survey.

Besides the inclination to retain farmland, Congress has robustly expanded the incentives to do so by way of changes in federal estate and gift taxes.

Jerry Cosgrove, adviser for AFT’s Farm Legacy Program, explains that, since Congress acted, “if you hold onto (farm assets) until you die, the basis (for capital gain tax) will be stepped up and there will be zero capital gains tax. And, as a practical matter, there is no estate tax now unless you’re very wealthy. The federal estate tax exclusions combined (for a married couple) are now more than $22 million.”

“There is really a strong disincentive now to transfer any appreciated asset, including farmland, during your lifetime, either by gift or by selling it,” Cosgrove said.

That deterrent may provoke a new surge in total farmland owned entities such as trusts, estates, corporations (usually family corporations), versus those owned by individuals or joint tenancy of farm couples. The tally for those entities has risen steadily, virtually doubling from 72,063 in 1982 to 142,370 in 2012, while the total number of farms declined, and the 2017 census results, expected in April, may contain a new record.

Also, farmers and landowners told ERS for its 2014 survey that they expect 62 percent of their farm and ranch lands will change hands through trusts, wills or gifts to family or others.

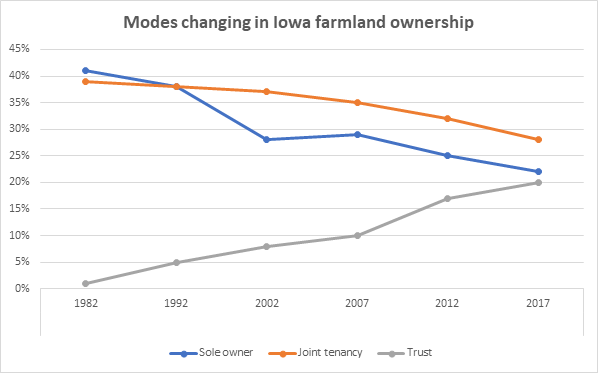

Results of the ISU tenure survey, taken as the tax changes were being completed, also suggest more farmland ownership is being parked in property holding the types of entities noted above. In the surveys of 2002 to 2017, farmland reported in individual and joint tenancy (or tenancy in common) shrank from 77 percent to 58 percent, respectively, while land reported in trusts, estates, corporations and companies swelled from 20 percent to 39 percent of Iowa farmland.

Source: Iowa State University Extension

However, that swing toward life-long ownership creates an economic barrier for young and beginning farmers trying to buy land, Cosgrove explains, because any landowner selling to them faces steep capital gains taxes. “So, people are just holding onto the land and renting it to the farm operators,” he says.

As a partial remedy, AFT and others are shopping a proposal among members of Congress and conservation advocates that would allow a one-time capital gains tax exclusion of up to $500,000 per person if selling land to a beginning farmer.

Some, however, think the impact of the tax changes may be exaggerated.

Says the ASFMRA’s Fevold: “I don’t think tax policy is as big a factor as what some might think it is. There are a lot of factors why people own land. I think a majority of landowners have more . . . things they’re worried about than tax policy. If they’re going to own land, they’re going to own land.”

Sure, family continuity is important for some landowners, says Fevold, who’s been a professional farm manager with Hertz Farm Management in Nevada, Iowa, since 1982. But, he says, “there are probably just as many families that want to sell the land and take the money and run.” Plus, he points out, “a little over half of the land in Iowa is owned by non-farmers.”

Indeed, non-operators’ share of U.S. farmland is substantial, and it is expanding beyond what has traditionally been held by retired farmers and those inheriting from them.

In the ISU survey, non-farmers’ share of all farmland is suggested in the tally of non-residents among Iowa farmland owners, which swelled gradually from 6 percent in 1982 to 20 percent in 2017.

Further, non-farmers’ share of rented land is much greater: In the ISU survey, 86 percent of leased acres belong to landowners who do not farm, and only 6 percent to someone who farms full time.

Nationwide, non-operators (including retired farmers) own 31 percent of U.S. farmland, a sizeable portion, according to the ERS 2014 report, but they own 80 percent of rented farmland. (Note, though, that retired farmers make up nearly half of the non-operator landlords, and their non-farming heirs are surely well represented in that category as well.)

Who are farmland buyers? By tradition, primarily farmers. They’ve long bought most of the tiny (under 1 percent) share of farmland that can be expected to show up annually in the open market and will pretty much keep doing so.

Dickhut says that Farmers National deals in farmland from the Pacific Northwest to the Midwest and Plains, Georgia and New York in the East, and elsewhere and “first,” he says, “there is not that much land that comes up for sale.” Plus “farmers buy 70-80 percent, sometimes more, of the good farmland that comes up for sale,” if sales for hunting and other recreational tracts are discounted.

Fevold, in Iowa, and Futch, in Florida, agree that farmers have long been the typical buyers and say that won’t change quickly.

But, Dickhut also thinks the tide has begun to turn in recent years. He says farmers were aggressive land buyers while farming was very profitable for most, up to about 2013. But in recent years, especially in some sectors and in some regions, such as dairy farms in the North and Northeast, he says, farmers are slower to jump at available land. “When things turned . . . the fun went out of it,” and more farmers are retiring, not expanding their holdings, he observes.

But now, “there is more interest by investment funds, like pension funds and venture capital in buying farmland,” says Dickhut, at least in the states allowing such purchasing. That’s the case in much of the country in the past several years, he says, with land prices easing up and fewer farms competing for farmland.

While a few years of poor farm profitability can nudge farmers to the land market sidelines, he said, “the investor buyers have the capital, because that’s their business . . . a pension fund or whatever . . . so they can buy any time” that the long-term investment outlook is favorable for it.

Futch, in Florida, agrees. “It seems there are more of the institutional people than farmers themselves out looking for farmland,” he says. “They’re buying farmland at an increased pace than, say, 15 years ago. In the last five years it’s become more popular.”

Futch observes growth in recent years in “investment groups that specialize . . . are diversified into many states and commodities, buying and leasing farms.” He works with one such group “that has farms in 13 states – everything from cotton in Arkansas to blueberries in Georgia to strawberry farms in Florida . . . even almonds in California.”

Most often, he says, “the investment buyers want leasebacks. They’ll go in and buy that farm, but the only way they’ll buy it is if they have that farmer or another farmer lined up to lease it back from them.” They don’t want to farm. “They are just looking for a return on investment . . . something around 5 percent.”

Who are the institutional investors in farmland?

Institutional investors have diverse backgrounds and interests in farmland. For example, The Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association (TIAA) closed a $3 billion farmland partnership fund in 2015 following a 2012 farmland fund of $2 billion. TIAA’s farmland partnership fund, Nuveen, invests in high quality farmland across four continents, including over 251,000 acres in the U.S. and almost 739,000 acres in Brazil, according to their 2018 report. For farm locations, see map below or click here.

Another investor group, Ceres Farms, acquires properties and leases them to local farmers who grow corn, soybeans, wheat or specialty crops on a scheduled rotation. In less than a decade, Ceres has acquired over 100,000 acres across ten states and has grown to over half a billion dollars in assets under management.

Conserving farmland

Another big trend is in conservation easements, which are rapidly expanding claims on U.S. agricultural land titles.

The easements are a partial ownership of land that prohibits or limits development and aims to protect wildlife, landscape or other conservation uses. They are funded by various national, state or local government entities and conservation organizations and are typically acquired by land trusts set up to own and manage them.

Some of the land trusts aim primarily or exclusively to retain agricultural use of land. Nationally, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service awards Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) grants to sponsor permanent easements on farmland. In fact, the 2018 farm bill ramped up funding, mandating $450 million a year for ACEP through 2023, up from $250 million in 2018.

Futch says that, among Florida’s agricultural land owners, selling conservation easements “is a good strong trend with people who are aging now and divvying up their property.” Many sell the easements “so the land can still stay in the family,” he says, and the sale means that “they get cash to work with,” even though the land will then list for substantially less – often about half of its previous value – because of the easement restrictions.

Land trusts and public programs have accrued 6.5 million acres of easements so far to specifically protect U.S. agricultural lands, representing a 38 percent increase in the past five years.

That is the tally from an ATF survey of nearly 700 land trusts in 2017, with results added to a listing of farmland protection easements held by public agencies and reported in December.

The land trusts oversee and manage the easements but rely heavily on public funding and money from conservation and other public-spirited entities to acquire the easements, says AFT’s Dempsey. “If they did not have public funding available . . . they wouldn’t be able to buy easements from agricultural land owners,” she explained.

Women, as well, are making headway in farmland ownership as in other parts of the American economy.

Women have long owned and controlled a big slice of America’s farm and ranch lands. Ag census data on female land ownership has been lacking for past decades, but the 2014 ERS survey says 37 percent of non-operator landlords are women, and they own 46 percent of the roughly 283 million total rented acres, or about 130 million acres.

The 2017 Iowa survey, meanwhile, found that women own 55 percent of leased farmland, up from 52 percent just five years earlier, but they also own 47 percent of all farmland in the state. In fact, women over 80 years old owned 13 percent of the farmland in 2017, the survey found.

Typically, woman have inherited their land from parents or have owned farms jointly with husbands and, because they most often outlive their husbands, end up with a larger share of the land than men among retirees.

Jennifer Filipiak directs AFT’s Women for the Land program and says “no one really knows . . . there’s just not a lot of data” about farmland ownership by elderly women. She holds meetings in the Midwest with women farmers and says, “most of the women who come in have inherited their farmland.” In the Midwest, she says, “there’s really a strong value around keeping the land in the family . . . since it’s been in the family so long.”

Jennifer Filipiak, American Farmland Trust

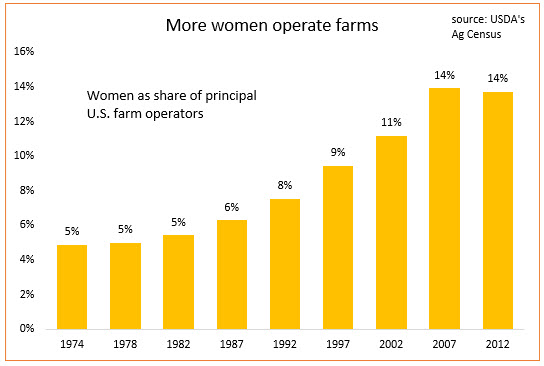

The rising number and share of American farms operated by women also points to increased ownership. It’s true that farms owned by women are, on average, much smaller than average, with gross sales only about a fourth of the national farm average, according to USDA. Keep in mind that USDA defines a farm as any place that produced and sold at least $1,000 of agricultural products during a given year.

However, USDA’s census records a run-up in women as the principal operators: from one in 20 farms a half century ago to one in seven in 2012. Besides, “smaller family farm operators are more likely to be full owners of land they operate,” USDA says.

Critical, too, to the ownership scene is land leaving agriculture – more than 1.5 million acres a year, on average, of cropland and range from 1992 through 2012. According to AFT, over 70 percent of urban development and 62 percent of all development happened on agricultural land, including woodlands that were part of farms.

At the same pace, more than 43 million more U.S. farmland acres – about 5 percent of the nation’s farmland – will no longer belong to any farmer but will become urban, industrial, commercial, residential properties and highways from 2012 to 2040.

Finally, here’s something unlikely to change much: the rented share of farmland.

Nationwide, “more than half of cropland is rented, compared with just over 25 percent of pastureland,” ERS says in its 2014 report. In general, rental activity is concentrated where grains, oilseeds, cotton and other major field crops are grown, and over 50 percent of farmland is rented in such areas.

But USDA’s census recorded the share of U.S. farm and ranch lands overall that were leased as 38 percent in 1964 and 1969. The share was still 38 percent in the 2012 census, and the ERS 2014 survey pegs the share at 39 percent.

The Disruptors: Six trends that will shape the future structure of U.S. agriculture

Farmers and ranchers have long been known for adapting and innovating, but new research challenges whether they are looking deep enough over the horizon to really win in the future.

“There are six forces of change in the industry that are pretty compelling,” says Brett Sciotto, CEO of Aimpoint Research, a global marketing research firm that has done extensive work analyzing current agricultural trends and identifying the “Farmer of the Future.”

“If you look at them collectively, it’s pretty indicative that we are going through a transformative period that’s only accelerating.” Consider these six trends:

Consolidation: Since the 1930s, the number of farms has declined, the average size has increased, and the amount of farmland in agriculture has remained generally flat. Of the 2.1 million farms in the last Census of Agriculture, only about 15 percent are at-scale production farms, and they control 80 percent of the acres. “We think by 2040, there will be fewer than 100,000 production farms, and 5 percent of farms will produce more than 75 percent of the agricultural output,” Sciotto says. “Mid-size farms are under the most financial pressure and are declining the quickest as they get bought up by larger operations.”

Aimpoint CEO Brett Sciotto

“However, there’s more to the story, and the ‘big get bigger’ statement is oversimplified. There are two classes of farms emerging - production agriculture and direct-to-consumer. According to USDA, the U.S. has seen a 61% increase in small farms from 1992 to 2012. Not every farmer will fit into today’s definition of production agriculture, and ag institutions will have to consider how they will serve both classes of farmers,” explains Sciotto.

Farmer psychology: Data suggest that more farmers may be unwilling or unable to stay in business if current economic conditions continue. US ag debt totaled $410 billion in 2019, a level that’s not been witnessed since the 1980s.

Farm operations have been “largely propped up by low interest rates and higher than average land values. We are starting to see the operating profitability of these farms declining and it’s making it harder and harder to pay back loans,” Sciotto says.

Last fall, research conducted by Aimpoint Research found that nearly 60 percent of farmers were concerned about their ability to repay operating loans.

“More lenders are thinking about their risks and more farmers are going to find it difficult to repay what they’ve already borrowed,” Sciotto says.

Compounding the situation is the transition of farmland and succession planning. USDA estimated between 2015 and 2019 that 10 percent of the farmland would change owners.

“In 2017, farmers told us 28 percent of the acres would transfer to a new owner in the next five years and 22 percent will have someone other than the current decisionmaker making decisions on cropping practices, inputs, and harvest. So, many farmers are perceiving a faster rate of change than what USDA estimated,” he adds.

“Sixty-five percent say they have a succession plan, but for many, that’s often a hope that a family member will come back to farm,” Sciotto says, “When you dig deeper, it’s likely less than half of farmers have a succession plan.

“There’s a correlation between whether producers have a family member coming back or not and how driven they are. For example, if you have a family member coming back to the farm, you tend to continue to invest in the operation. You find new efficiencies and expand and grow. If you don’t have someone coming back to the farm, you tend to pull your foot off the gas pedal earlier.”

Technology: A lot of young people are interested in agriculture, and when Aimpoint Research asked what excites them most, new technology came up loudest. USDA says nearly 69 percent of young farmers will have college degrees.

“Those who are coming back to the farm are going to be more educated than their parents and grandparents before them. They intend to do things differently. They grew up in a disruptive era. They don’t necessarily have the same appreciation for the lifestyle that their parents and grandparents did. They don’t want to wake up one morning, work on the farm all day, eat dinner and do it again the next day. They want to run a very efficient operation, they want to make money. They want to have other interests and do other things,” he adds.

Seventy-five percent of farmers 35 and under said, “As soon as I’m in charge, I’m going to integrate new technology,” according to Aimpoint Research. At the same time, 71 percent plan to increase efficiency, 63 percent plan to improve marketing and 48 percent plan to expand acreage.

Technology is having a different effect on ag than it has in the past, says Sciotto.

“Like with marathons, when the gun goes off, there is a huge gaggle trying not to trip over each other. But that group of runners is largely spreading out. We see that farmers who are willing and able to adopt new technology are getting further ahead and those unable or unwilling to do so are falling further and further behind. That’s impacting who is likely to be successful in the future.”

Consumers: Consumers are the center of gravity that’s propelling a lot of the change in agriculture, and about two-thirds said they are thinking about where their food comes from, according to a recent Aimpoint Research survey. “What really drives consumer decision-making is price, healthiness and freshness,” says Sciotto. “And what consumers perceive is largely what retailers are adapting to. Consumers perceive that non-GMO is better than GMO and that organic is better than non-organic. They also perceive that local is better even though the definition of local varies from a ‘farm in my community’ to a ‘farm in the U.S.’ We, in ag, know that a lot of those belief systems may be unfounded or unrealistic but, nonetheless, retailers are responding.

“Organic continues to grow and we see the emergence of new innovations in protein like the Impossible Burger and Memphis Meats. Many traditional protein companies are investing because – even though lab-based protein sources could still be 5-10 years off, they could be significant disruptors and put pressure on corn and soybean markets in the U.S. if some of the livestock production shifts.”

Consumer interest in electric vehicles could be another disruptor, Sciotto says.

“By 2040, it’s very likely we could see a significant decline in the number of combustion engines. If you lose ethanol – which consumes about 40 percent of the U.S. corn crop today – it will lead to significant changes,” he adds.

“Between alternative proteins, the regulatory pressures on animal agriculture, shifting consumer patterns and the potential loss of ethanol, I think there could be a significant amount of acres under some level of risk,” Sciotto says.

Sciotto expects more food companies and retailers to cater to what their consumers believe they want – whether it’s founded in good science or insights, or not. And those decisions end up down on the farm.

“We will see the retailer asserting more and more pressure on how farms are run. When you ask consumers who they trust more – food companies or farmers, 58 percent say the farmer. But the farmer seems to be losing more and more control,” Sciotto adds.

Markets: Commodity prices have been relatively low, but that hasn’t stopped farmers in many parts of the world from increasing production. As the global population continues to grow, analysts estimate that we’ll need a 70 percent increase in the food supply.

“South America is likely to become the breadbasket of the future. American farmers are in a tougher competitive environment as markets shift and new players emerge stronger to meet global demand,” says Sciotto.

Government: The farm bill has historically played an important role in providing support for many farmers and rural areas through commodity programs, crop insurance, conservation, and rural development. The Congressional Budget Office projects the 2018 Farm Bill will cost $428B over the next 5 years.

However, other aspects of government policy, like trade and monetary policy, can also put operations at risk. As a result of the trade war, the value of total U.S. agricultural exports in 2019 is expected to fall to $141.5 billion, down $1.9 billion from 2018, according to the Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) latest projections.

In addition to ongoing concerns about trade, labor and regulatory reform continue to be top issues. Most growers believe federal regulations have generally been harmful to agriculture, according to Aimpoint Research.

Sciotto says all six of these trends are converging and the speed is accelerating. “It’s putting a lot of pressure on farmers and on traditional institutions of agriculture.”

“We have to acknowledge as an industry that we are going to serve a bifurcated market. We are going to have large, sophisticated vertically-integrated operations run by high business IQ farmers and we are also going to have small, direct-to-consumer operations serving their niche.”

Sciotto says agribusinesses who serve traditional agriculture will have to move faster and add value.

“The concept of one-size-fits-all is fading in farm channels. The farms of the future will be diverse, have different needs and will look to their vendors and suppliers to provide tailored solutions and to be constantly innovating.”

For more news go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com