WASHINGTON, Nov. 10, 2016 - The 2016 presidential election presented a clear choice on climate and energy. One candidate, Hillary Clinton, pledged to expand the Obama administration’s policies designed to combat climate change and to accelerate the nation’s shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy. The other major candidate, Republican Donald Trump, promised to promote more traditional energy sources like coal, oil and natural gas and withdraw from international climate change agreements.

This stark contrast at the top of the ticket virtually guarantees that the high-stakes battle over climate and energy policies will continue. Regardless of White House actions over the next four years, Congress is likely to reflect the divided electorate and remain gridlocked, forcing the White House to follow the examples set by presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama in relying heavily on controversial and reversible executive orders.

Deep ideological divisions within Congress and the Supreme Court are likely to continue and to limit the ability of either the White House or Congress to implement consistent climate and energy policies. As a direct result of the prospect that division and uncertainty will continue at the federal level, policies set by individual states could become increasingly important.

One example of a state aggressively leading the way on energy and climate issues comes from North Carolina, the only state mandating that utilities include electricity generated from animal wastes in their energy mix.

Every year since 1997 when North Carolina set stringent environmental requirements for any new or expanded swine operations with more than 250 hogs, opponents have tried unsuccessfully to repeal or at least amend the requirements. Yet after repeated year-to-year renewals, North Carolina’s Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard (REPS) became permanent law in 2007, providing strong carrot-and-stick incentives to turn animal waste into renewable energy.

The REPS law, the first renewable energy portfolio standard in the Southeast, requires that “all electric power suppliers in North Carolina must meet an increasing amount of their retail customers’ energy needs by a combination of renewable energy resources (such as solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal and biomass) and reduced energy consumption.” This mandate includes a specific requirement that utilities use swine waste biogas as the source for a small but increasing share of the electricity they deliver each year.

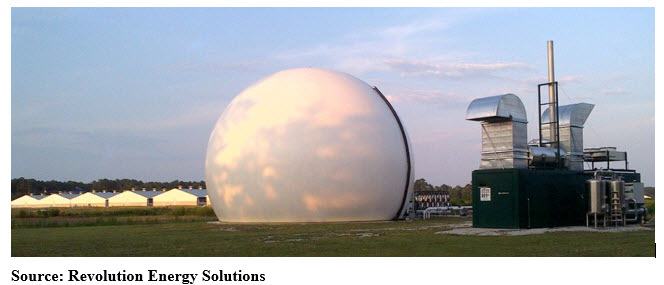

North Carolina remains a distant second to Iowa in pig production. But the Tar Heel State ranks No. 1 in its so-far unmatched mandate that its 9.1 million pigs on 2,100 permitted hog farms become better neighbors by turning their odiferous waste disposal problem into an energy success story. To make this waste-to-energy process work, Revolution Energy Solutions (RES) has built custom-tailored anaerobic digester systems in North Carolina and Oregon to generate electricity from biogas methane and co-generate the heat needed to operate the digesters most efficiently.

In Magnolia, North Carolina, waste from hog barns shown on the left go to 10 anaerobic digesters to fill the inflatable “biosphere” with biogas methane which powers the electric generator housed in the on-farm combined heat and power (CHP) plant on the right.

Alan Tank, RES founder and managing partner, tells Agri-Pulse that the U.S. lags far behind

Germany in building waste-to-energy systems because the U.S. lacks Germany’s

consistently supportive federal policies. He says the result is the disparity

between “some 175 digesters on livestock farms across the U.S.” versus over

9,000 in Germany.

Alan Tank, RES founder and managing partner, tells Agri-Pulse that the U.S. lags far behind

Germany in building waste-to-energy systems because the U.S. lacks Germany’s

consistently supportive federal policies. He says the result is the disparity

between “some 175 digesters on livestock farms across the U.S.” versus over

9,000 in Germany.

Tank says RES built the systems in North Carolina and Oregon thanks to supportive state policies. But he says the company abandoned its plans for additional facilities in Oregon after the state eliminated its tax break for biomass energy from dairy farms.

RES also considered investing in both California and New York, adding value to the states’ large dairy industries, but found both states had regulations that presented more barriers than support for biomass energy.

In the case of California with the nation’s largest dairy industry, Tank says, “it was very difficult to get an air permit to be able to operate a CHP (combined heat and power) unit.”

Tank considers North Carolina the best location currently for new waste-to-energy investment thanks to favorable state policies and strong support from a major power company, North Carolina-based Duke Energy. He praises “Duke’s willingness to lead, to participate, and to find solutions.” But even in supportive North Carolina, he points out that the state, by recently ending a tax credit, has made it more difficult for biomass energy projects to pencil out.

To take full advantage of the vast untapped potential for biogas power from animal waste, Tank insists that it’s time to catch up with Germany and replace the current unstable “patchwork” of inconsistent regulations with a stable national renewable energy portfolio standard. He says this national approach should be “designed to incentivize and de-risk taking a waste stream and converting it into energy.” He sees consistent national policies as the only way to attract far greater investment and to level the playing field with the petroleum industry that, he points out, still enjoys significant financial support at the federal level.

“We should go through a process in this country of really

understanding our entire energy system, everything from a renewables portfolio

standard to the actual grid itself, to all the other dynamics in the

marketplace affecting energy,” Tank says. He calls for replacing today’s “patchwork”

of state regulations, where in some places there is little assistance, and

others “where it is working very well like Iowa in the context of wind and

ethanol.” Regretting that his home state of Iowa hasn’t followed North

Carolina’s biomass energy example, he’d like to see Iowa and the nation as a

whole generating energy from livestock waste rather than continuing to rely so

heavily on fossil fuels.

“We should go through a process in this country of really

understanding our entire energy system, everything from a renewables portfolio

standard to the actual grid itself, to all the other dynamics in the

marketplace affecting energy,” Tank says. He calls for replacing today’s “patchwork”

of state regulations, where in some places there is little assistance, and

others “where it is working very well like Iowa in the context of wind and

ethanol.” Regretting that his home state of Iowa hasn’t followed North

Carolina’s biomass energy example, he’d like to see Iowa and the nation as a

whole generating energy from livestock waste rather than continuing to rely so

heavily on fossil fuels.

Calling for using the full range of available organics including manure, food processing wastes, and cellulosic materials, Tank insists that “We need to be thinking about a comprehensive strategy that results in a federal policy for producing energy from agricultural and food sources” to create value while improving “waste management, nutrient management, water quality, and air quality.”

The North Carolina Pork Council’s Policy Development Director Angie Maier tells Agri-Pulse that thanks to steady support from the pork industry and Duke Energy, North Carolina now has six major waste-to-energy operations turning hog manure into biogas and electricity. She adds that additional facilities are being built, as confirmed recently by Duke Energy and Carbon Cycle Energy joining forces to turn hog waste biogas into renewable electricity at four of Duke’s North Carolina power stations.

In a win-win for both hog farmers and the utility’s electricity customers, David Fountain, Duke Energy president for North Carolina, said in announcing the new biogas project that “It is encouraging to see the technological advances that allow waste-to-energy projects in North Carolina to be done in an environmentally responsible and cost-effective manner for our customers.”

Alan Tank, meanwhile, looks forward to the day when consistent federal policies trigger a surge of such waste-to-energy projects nationwide rather than just in North Carolina.

#30

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com