A recent broadband coverage map released by the White House further illustrates rural America is in dire need of faster internet speeds, but at least one rural state is doing better than most, thanks to a commitment by local providers.

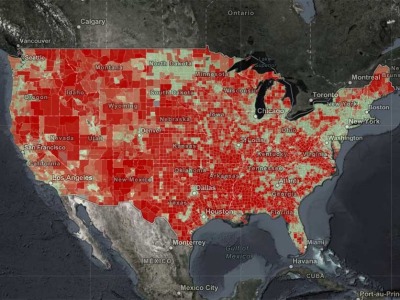

A new interactive map developed by the White House and National Telecommunications and Information Administration attempts to illustrate the nation's digital divide in two colors — red for areas that need access to high-speed internet, defined as at least 25 megabits per second download and 3 megabits per second upload speeds, and green for areas with adequate service. That broadband service definition has been used by the Federal Communications Commission since 2015.

Most of the green areas are around major U.S. cities like New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., but North Dakota is among them. Almost the entire state is shown in a minty hue except for a few counties on its northern and southern borders.

David Crothers, executive vice president of the Broadband Association of North Dakota, gives the credit to locally controlled providers. “These are locally owned companies that have boards of directors that are committed to delivering the services that those that live within their communities need,” he told Agri-Pulse, saying other states rely more on outside providers.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration/White House interactive broadband map. The red indicates areas with service below 25 megabits per second download speeds.

He said members of his association serve 97% of North Dakota with broadband. Within that number, 98% is covered with fiber broadband, or fiber optic cable. The remaining 2%, he said, will be serviced in three years. Some 15 member companies have offered gigabit service — which offers download speeds of 1,000 megabits — to over 300 North Dakota rural communities, he said.

One of those members is Dakota Carrier Network. Seth Arndorfer is the company’s CEO and said rural broadband service providers have installed over 40,000 miles of fiber into the most rural corners of the state.

He told Agri-Pulse those installations make it possible “to support gigabit internet access out to the farm and precision ag deployments whether they are wired or wireless.”

North Dakota providers have been able to afford the cost of fiber because of federal funding programs, including the Broadband Technology Opportunities Program that was signed into law in 2009, the Federal Communications Commissions' Universal Service Fund, and most recently USDA's ReConnect program, Arndorfer said.

North Dakota's flat, open landscape and accommodating soil make it relatively easy to lay fiber over long distances, said Arndorfer. He also noted that small telecom companies are committed to rural communities they serve with state-of-the-art technology, highlighting that the state "is served by these rural broadband service providers and not by a national corporation."

Janie Dunning, a broadband consultant for the Missouri Farm Bureau, said North Dakota is doing so well with broadband service due to an “overwhelming amount of telecommunications cooperatives serving consumers."

She said telephone cooperatives have grassroots board members in North Dakota that are willing to take out available USDA rural development loans and grants to serve rural customers even though they know the return on investment will be minimal. The telephone cooperatives' mentality is that “they are there to serve rural (customers) regardless of the profitability,” she told Agri-Pulse.

She agreed that North Dakota’s landscape is conducive to laying fiber, and there also were already existing easement corridors.

Interested in more news on farm programs, trade and rural issues? Sign up for a four-week free trial to Agri-Pulse. You’ll receive our content - absolutely free - during the trial period.

Burying the fiber cable is not as easy in Missouri. “We have more rocks, mountains, hills, and forests than North Dakota does,” she said.

Bharat Ramamurti, deputy director of the White House's National Economic Council, noted North Dakota's broadband success during a recent press call to roll out the coverage map. Ramamurti said the White House map is intended to show where people are online at slow speeds and where large percentages of people lack an internet-connected device.

He said the map was intended for educational purposes and wouldn't be used by Congress to make fiscal decisions on funding broadband internet. Ramamurti also said the map doesn't affect the FCC’s effort to improve its own national broadband map.

But NCTA-the Internet and Television Association, a Washington-based group that represents many broadband providers, said the overall picture on the White House map overstates the amount of existing broadband service.

“Unfortunately, NTIA has obscured, rather than clarified, the true state of broadband with this mashup of disparate, and often inaccurate, data sources,” NCTA told Broadcasting+Cable recently. “In particular, any suggestion that data from M-Lab or Microsoft accurately represents the speeds delivered by cable operators is demonstrably false,” the group said.

Dunning, the Missouri Farm Bureau consultant, agreed that until more granular broadband coverage data is collected, "any map is going to be overstated."

Congress and the Biden administration are continuing efforts to fund broadband infrastructure build-out with the hopes of turning more areas the color of North Dakota on the next coverage map.

A bipartisan Senate infrastructure agreement designates $65 billion for broadband, enough money to ensure that every American has access to high-speed internet, according to the White House.

In the meantime, states also are eligible to use some of their existing federal coronavirus relief funding for broadband development. The Treasury Department's interim final rule regulating how the broadband funding is to be used defined eligible areas as lacking broadband speeds of at least 25/3 Mbps, the same definition the FCC has been using.

National Grange, a community-based ag organization, supports the definition and said it “sets the right priority by ensuring that government funding first reaches the truly unserved areas of the country, including farms, ranches, their households and their neighbors, that have historically been persistently unconnected.”

However, some lawmakers have pushed for a minimum speed of 100 megabits per second download and 100 megabits per second upload. Crothers and Arndorfer both agree the minimum level of service should be increased.

But National Grange President Betsy Huber said raising the minimum speeds is problematic.

“It will only divert government funding to more densely populated urban and suburban locations that are currently adequately served with more than sufficient broadband speeds,” she said in a letter to the Treasury Department.

Huber argued that the Treasury Department rule “sets the right balance” by establishing an eligibility standard ensuring unserved areas get connected.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.