Although the presidential debates are ahead of us, the debate on increasing the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage cap has already begun. My concern is that we don’t expand conservation on idle lands at the expense of environmental protection on working lands.

The 2014 Farm Bill reduced the CRP acreage cap gradually from 32 million acres to 24 million by 2018, a savings of $3.3 billion over 10 years. Ratcheting down CRP acres by 25 percent was a deliberate budget saving effort. So, if those acres go up with the 2018 Farm Bill, some other program must be cut to cover the average $72 cost per CRP acre. Furthermore, there’s a good chance that even less funding may be allocated to agricultural conservation in the next farm bill if the House and Senate are inclined to reduce spending overall to control the nation’s deficit.

CRP enrollment peaked in Fiscal Year 2007 at 36.8 million acres. Today 23.8 million acres are actually enrolled through more than 650,000 contracts on more than 365,000 farms.

Under the 2014 Farm Bill, the acreage cap for 2017 and 2018 is set at 24 million acres, and the President’s FY2017 budget requests a little more than $1.9 billion to pay for CRP contracts next year. In 2016, about 411,000 acres were approved for CRP under general sign up and 528,000 acres thus far under continuous sign up. About 5.7 million acres are set to expire by September 30, 2018.

Much of the CRP acres that are expiring this year and over the next two years are in grass and trees. There is also significant acreage in permanent wildlife habitat and rare and declining habitat along with filter strips, riparian buffers and wetland restoration.

As we look at renewing contracts on expiring acres or raising the acreage cap, we need to be sure that the program focuses on environmentally sensitive acreage, and we don’t wind up with high quality land under CRP contracts. At the birth of the CRP program, it was used to short the corn and wheat supplies – let’s not make that mistake again. That is why I have always favored putting conservation on working lands over idling land—programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). When we use CRP in the conservation portfolio of tools we should use it surgically and strategically to trap and treat nutrient runoff or to provide specific habitat benefits rather than large-scale whole field enrollments.

If there is a case to be made for funding additional CRP acres, we must be sure it is not accomplished by cutting into monies set aside for conservation on working lands. One alternative source of funding we could tap is the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Congress has noted that a considerable portion of the funds under LWCF in recent years have been used for federal land acquisition. I would rather see us accomplish conservation on lands that remain in private hands.

LWCF uses a small portion of federal offshore drilling fees to protect and conserve land to benefit wildlife, increase recreational opportunities and conserve forest and ranch lands. I am pleased that LWCF has begun to turn to conservation easements on private land to accomplish its goals, which are similar to those of CRP. Using LWCF monies to fund additional CRP acres makes a lot of sense to me if we want to increase the acreage cap in the next farm bill.

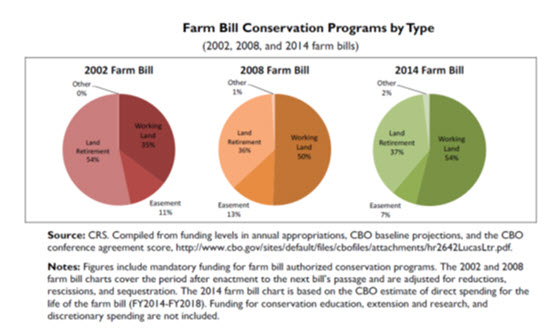

As we look at agricultural conservation programs for the next farm bill, we may have some tough choices and tradeoffs to make. In that case, I hope that conservation programs for working lands will continue to grow in size and importance as they have in the past few farm bills as shown below.

#30

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com