For months, Republicans and Democrats in Congress have pointed fingers at each other over the rising cost of goods including food as the midterm elections quickly approach, but there are big doubts about how effective any of their proposals will be.

Recent reports by food economists including the Agriculture Department’s Economic Research Service and the Consumer Price Index show the factors driving inflation are largely out of legislators' control.

An outbreak of avian influenza has driven up the price of poultry and eggs by reducing stocks of chickens. Drought conditions in the West and increases in transportation costs have caused fresh fruit and vegetable prices to soar. And the ongoing war in Ukraine has resulted in a massive upheaval in the global supply of wheat, grains and oilseeds.

ERS’ latest Food Price Outlook, released Wednesday, projects that supermarket prices will increase by 7% to 8% this year.

Egg prices are projected to be 19.5% to 20.5% higher. Poultry prices are forecast to rise by 8.5% to 9.5%, dairy prices by 7% to 8%, and prices for fats and oils by 10% to 11%. Beef prices are expected to increase 6% to 7%, while fruits and vegetables are forecast to cost 6.5% to 7.5% more.

Economist Dan Basse, president at AgResource Co., told Agri-Pulse he doesn't see food prices retreating this year unless the U.S. boosts production.

"If you want to bring food prices down, we need to produce more of it," Basse said. "Or you need to tell consumers that they need to consume less. The market will do that through higher prices, but that's not, of course, helping the Biden administration [with] the message they want to send."

Still, legislators are trying their hand at slowing the rise in consumer prices – even if the results will be futile – to show voters they are doing something.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., who has been one of the most vocal voices for Democrats on inflation, penned an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Democrats Can Avoid Disaster in November."

“Democrats win elections when we show we understand the painful economic realities facing American families and convince voters we will deliver meaningful change,” Warren said, adding that Democrats can “act quickly to rein in costs for middle-class families."

Democrats have targeted consolidation in the ag market as they’ve sought to lower food prices.

Sens. Cory Booker, D-N.J., Jon Tester, D-Mont., Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., and Warren recently introduced a bill that would put a moratorium on agribusiness mergers, promoting the legislation as an opportunity to bring down consumer prices.

Booker said in a press release that the Food and Agribusiness Merger Moratorium and Antitrust Review Act of 2022 would halt continued industry consolidation. He said over the past 40 years, "the top four firms in nearly every sector of the food and agriculture economy ... have exercised undue influence over federal agriculture policies, driven family farmers and ranchers out of business, and increased food prices to pad their profits while consumers pay more at checkout lines."

Warren also tied consolidation to the increase in prices, saying in the release that “it's time to stop mergers that hurt workers and that enable the corporate price gouging that’s leading to higher costs for American families — this bill would help us do just that.”

A companion measure to the bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Mark Pocan, D-Wis.

Senate Ag Committee Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., has been a vocal proponent of a bill that would mandate more cash trading in cattle markets. The bill is directly targeted at the four largest meatpackers in the U.S.

"Consumers all saw empty shelves and sky-high prices at the grocery store, all while huge companies reaped record profits," she said at a hearing on the bill. "Our food supply chain, while efficient, also proved to be highly vulnerable. Consolidation and lack of competition was a significant contributing factor."

But Basse said efforts to reduce consolidation may not be effective.

"I think a lot of times Washington likes to point fingers and tinker around the edges and blame price discovery [but] there's been no evidence at least at the moment that the cattle market is broken," he said. "On the consolidation thing, we also see that data is clear ... bigger farms or bigger operations tend to be more economical and have more advantages to supply production [and] should be producing more, not less."

Republicans, meanwhile, are betting the inflation issue will help them win control of the House and Senate.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

"I think the election this fall is going to be about inflation," Florida Sen. Rick Scott, who chairs the National Republican Senatorial Committee, told CBS' Face The Nation last weekend. "And I think it bodes well for Republicans."

Some Republicans have been calling for increases in production to counter inflation and hammering the administration as prices continue to rise.

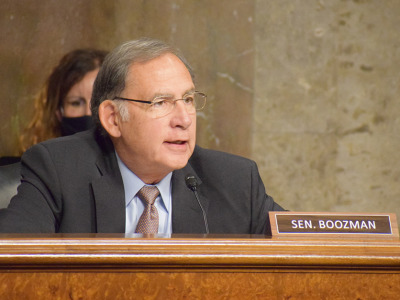

“Food prices will decrease when the costs from the farm to the fork go down," the Senate Ag Committee's top Republican, John Boozman, R-Ark., told Agri-Pulse. "The answer is more supply. More fuel for lower energy prices, more participation in the labor market, more land in production, and more certainty for our farmers and ranchers.

Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark.

Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark.“Until the administration starts to focus on the core issues that are driving record food costs, there will be no relief and American families will continue to suffer," Boozman said. "I will keep making that case to the administration and my Democratic colleagues and encourage them to work with us to help create an environment where those factors start trending in the right direction and prices come down."

Boozman has pushed for allowing farmers to plant on some acreage in the Conservation Reserve Program. The Biden administration is going to allow landowners with expiring CRP contracts to prepare the land for fall planting, but much of the acreage is in areas of the Plains that are gripped in a severe drought. However, Basse said it may be the only option to increase production and lower prices in the near term.

Basse said climate change has been a driver behind slowing global grain yields, and that 20-25 million extra acres are needed around the globe to meet demand. In the U.S., that land could only come from acreage now idled in CRP, he said.

"It's surely not our best farmland, and we can all question about how much supply it would actually produce, but I don't know what else to do if the U.S is indeed at peak farmland," Basse said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.