First of all, those looking for spring fertilization options are in the minority. The majority of farmers have already bought most of the crop promoters they need for 2018 crops, and much of it went into their fields last fall.

In part, that’s because Mother Nature gave farmers a generous dry window for fall application. Though much of the Corn Belt had a somewhat wet October, National Weather Service data show that November rainfall was just 10 to 75 percent of normal for nearly all of the U.S. east of the Rocky Mountains, and December was nearly as dry overall, except in the northern Rockies and parts of the Northern Plains.

Meanwhile, farmers who must still fill spring fertilizer needs can expect both tolerable prices and good market access. Farmers operating a decade ago can painfully recall prices on ammonia fertilizer and diammonium phosphate (DAP), for example, topping $1,000 a ton. Fortunately for farmers, current prices are a third to less than half of those levels, and some – potash and UAN32 (a liquid nitrogen solution), for example – have been quite stable the past year.

The notable exception is nitrogen fertilizers, which make up around 60 percent of field fertilizers. The tab for the main ones has crept up a lot since last fall: urea to typically $350 or more a ton, on average, at local outlets, up around 10 percent; anhydrous ammonia, to nearly $500 a ton, up around 20 percent. Nonetheless, recent ammonia prices are still less than the $509 average that USDA lists as the average for the 2017 crop year.

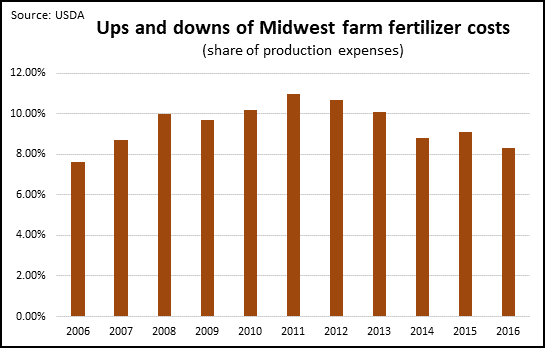

In general, spending for fertilizers has eased in recent years as a share of total crop production costs. U.S. farmers spent about 5 to 6 percent of their crop budgets on fertilizers up until 2006, according to USDA surveys. That share swelled to 8 percent when demand for fertilizers soared along with crop prices through 2011, but has retreated to under 7 percent in recent years. The price run-up was even greater in the Midwest (see chart), but has plunged there as  well.

well.

In that region, Gary Schnitkey, agricultural economist at the University of Illinois, keeps annual production budgets for major crops in Illinois, and they show a broad retreat for fertilizer costs. For mid-state acreage, he reports average fertilizer costs for corn, a very nitrogen hungry plant, tumbled from $200 an acre in 2012 to $134 in 2017, and he projects a further $5 dip for 2018. The decline largely reflects the plunge in nitrogen fertilizer prices: ammonia fell by $340 a ton, on average, from 2012 to 2017.

Meanwhile, for soybeans, which fix nitrogen in the soil but need lots of potash, Schnitkey projects an average fertilizer cost of $36 per acre in mid-state fields, down nearly 50 percent since 2012. That decline tracks with potash fertilizer prices, which averaged just $312 a ton in 2017, or half what they were in 2012, he indicates in a review on fertilizer costs.

Schnitkey notes that the projected 2018 slippage in fertilizer costs may also happen “because of reduced fertilizer rates to meet a low cash flow.”

Natural gas prices – a principal driver of nitrogen fertilizer prices because it is their primary ingredient – so far show little threat of driving fertilizer prices up this winter. A January cold snap lifted the February futures (Henry Hub) price up nearly a dollar, to around $3.50 per million British thermal units (Btu), from last fall’s deep discount. What’s more, the U.S. Energy Information Agency last week reported that recent cold weather demand had sent nationwide gas stocks down 18 percent from year-ago volumes.

Despite all that, the U.S. faces no gas shortage, and EIA forecasts natural gas production to increase in both 2018 and 2019, exceeding domestic consumption of natural gas for the first time since 1966. So, not surprisingly, futures prices for the upcoming months have plunged back to $2.80 per MBtu, and EIA expects prices under $3 for both 2018 and 2019.

Note, too, that winter delivery of fertilizers to outlets throughout the Mississippi and Ohio river navigations systems appears free of interruptions, for now, except for a brief holdup on the upper Ohio River, where ice accumulations and barges adrift forced a closing of the Emsworth Lock downstream from Pittsburgh.

There was a similar difficulty briefly on the Ohio River at Moundsville, WV, said John Kelly, public affairs officer for the Pittsburgh District of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. But “we’re back in business,” he said last week.

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com