From California to Georgia, farmers can’t find enough workers to harvest their crops or milk their cows. Combined with Congress’s decades-long failure to act on long-promised comprehensive immigration reform, the result is that U.S. consumers are paying more for a less-secure food supply as more production moves south of the Mexican border in search of farm labor.

But a fix could be slowly brewing, thanks to White House intervention being led by Jared Kushner, special advisor to President Trump. Helping this effort is immigration expert Kristi Boswell, an attorney who was Director of Congressional Relations for the American Farm Bureau Federation before moving to USDA as senior advisor to Ag Secretary Sonny Perdue, then on to Kushner’s White House Office of American Innovation.

Jaime Castaneda, senior VP of policy strategy and international trade at the National Milk Producers Federation, points to past efforts on comprehensive immigration reform raising hopes, then failing each time. With 2018’s latest attempt, he tells Agri-Pulse, “We got stuck again.”

Jaime Castaneda

But Castaneda’s hopeful about a breakthrough this year. First, he welcomes the Kushner/Boswell intervention and President Trump’s repeated acknowledgments that the farm sector has special needs. Castaneda also sees heightened congressional interest in “bipartisan legislation focused on agricultural immigration.” He says targeting ag, without adding the complexities of comprehensive immigration reform, “could grease the path to something bigger.”

The “doable” next step, Castaneda says, is for Congress and the White House to agree on legislation that “takes care of agriculture’s current workers. But no legislation will move forward without addressing the unique needs of dairy for year-round workers, because the current H-2A program’s limitations to only seasonal and temporary jobs hurts both workers and agriculture.”

The driver for this next step is today’s tight farm labor supply. Just how tight is shown in the California Farm Bureau Federation (CFBF) 2019 Farm Worker Scarcity Survey published April 30 with UC Davis. It concludes that “farmers face continuing challenges in agricultural employee availability. In California alone, farmers and ranchers hire nearly 473,000 employees during peak season. National estimates put the agricultural workforce at 2.5 million hired employees.”

The report adds that “Experts calculate that 50 to 70 percent of the hired workers are not authorized to work in the U.S.” This large percentage of undocumented farm workers means at least half of farm workers risk deportation while their employers face the constant threat of losing their workforce without warning and without available replacements.

In response to what CFBF’s 2012, 2017 and 2019 surveys show as an increasing labor shortage, the 2019 report calls for “agricultural workforce reform that provides existing employees with a legal status and allows entry for future guest workers who desire to work in U.S. agriculture.”

The 2017 survey concluded that “despite raising wages, increasing benefits, converting to less labor-intensive crops, investing in mechanization and other efforts, California farm employers have experienced continued employee shortages, and have continued to alter their production practices in response to the shortages, which stem in part from a lack of agricultural labor reform at the federal level.”

In its 2012 survey, CFBF warned that farmers have responded by adjusting crop plantings, competing for employees by offering year-round employment, investing in mechanization if available, or transferring some production to other countries. The farm group concluded that “No matter which of these options farmers take in response to chronic employee shortages, the impact will affect the crops grown, the diversity and the long-term economic value of California agriculture.”

Part of the problem is that “Nobody, including farm workers, is raising their kids to be farm workers.” That’s according to California farm labor contractor Steve Scaroni. His fast-growing Fresh Harvest company supplies legal migrant workers to farmers in California, Oregon and Washington under the federal H-2A visa program that legalizes hiring seasonal migrant labor.

Scaroni tells Agri-Pulse H-2A is sorely needed but  far short of meeting farm labor needs due to the program’s high costs for farmers and complex regulatory burdens. As a result, he says, too much fruit and vegetable production has already shifted from California to Mexico. This shift included Scaroni setting up his own Harvest Tek de México company 14 years ago to raise produce in Mexico for the U.S. market because he “saw a lack of labor and major cost escalations coming to United States agriculture.”

far short of meeting farm labor needs due to the program’s high costs for farmers and complex regulatory burdens. As a result, he says, too much fruit and vegetable production has already shifted from California to Mexico. This shift included Scaroni setting up his own Harvest Tek de México company 14 years ago to raise produce in Mexico for the U.S. market because he “saw a lack of labor and major cost escalations coming to United States agriculture.”

As operated currently, H-2A includes requirements that farmers pay above-market wages to H-2A workers along with providing free housing, transportation and other benefits. The requirements are designed to encourage farmers to prioritize hiring U.S. citizens instead of migrant workers. Scaroni says the only answer is to “recognize that legal United States residents are not going to do farm work” and therefore “We’ve got to design a system that facilitates bringing in migrants from other countries on a temporary basis.”

Bill Brim, raising vegetables, cotton and peanuts on Lewis Taylor Farms’ 6,500 acres in Tifton, Georgia, testified in a House Judiciary hearing April 3 that “without access to what used to be a steady stream of workers, more and more farmers began turning to the H-2A program, not because they wanted to, but because they had to. It was, and still is, despite the bureaucracy, costs, and uncertainty, the only viable option to hire farmworkers who are legally authorized to work in the U.S.”

Brim pointed out that he had to increase his efforts to hire locally because “The porous southern border that once enabled workers to relatively easily cross into the U.S. began changing after 2001. Since that time, border security has dramatically increased. Worksite enforcement has dramatically increased.” The result, he said, is that “tighter security at the border, tighter security in the interior of the country, and tighter security at the worksite has led to a tighter labor market for agriculture.”

“There simply are not enough U.S. workers who are willing and able to do this work,” Brim explained. “The hiring statistics from our farm illustrates the story very well. Last year, we had nearly 900 positions certified as eligible to be filled by H-2A workers. Just ten U.S. workers responded to fill those positions and they were hired, but eight of them did not finish the season.”

Daniel Hartwig, resource manager for Woolf Farming, tells Agri-Pulse the family-owned operation’s 20,000-acre main ranch in Huron, California also has been experiencing serious labor shortages. “We’ve mechanized where we can,” he tells us, “but especially at harvest time, labor is really tight.” He adds that because the H-2A program “is just really, really difficult to use . . . no one around here uses it.”

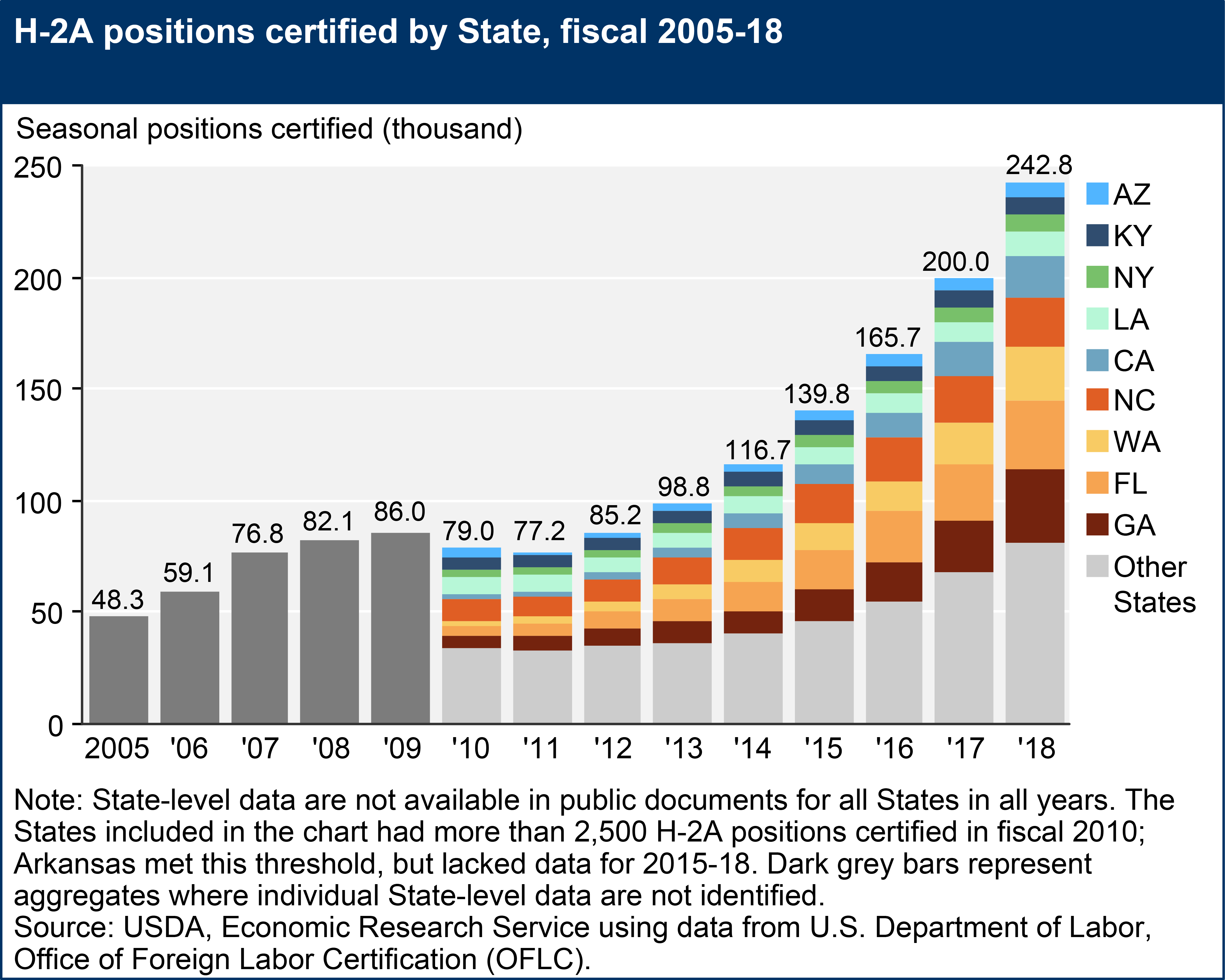

Yet increasingly, as the graph below shows, H-2A use has surged, with nearly 250,000 H-2A contracts signed last year. With this surge, H-2A workers now provide about 10 percent of agriculture’s estimated 2.5 million hired employees.

California Farm Bureau Federation President and Lodestar Farms olive grower Jamie Johansson tells Agri-Pulse California’s use of the H-2A program has grown from about 8,000 workers in 2015 to over 18,000 H-2A workers in 2018. “It’s increasingly important and the primary reason,” he explains, “is desperation for labor by our farmers. So H-2A is almost serving as a last resort for a lot of farmers, using H-2A to get the labor they need.”

Jamie Johansson

To deal with the growing worker shortage, Johansson says, “getting comprehensive immigration reform really is one of our critically important issues this year in this new Congress.” As part of the reform, he’d like to end the bureaucratic chaos created by the fact that USDA shares H-2A program responsibility with the State Department, the Department of Labor, and Homeland Security.

To fix the farm labor shortage, California Farm Bureau’s Farm Employers Labor Service COO Bryan Little tells Agri-Pulse that the first step is to provide legal status for undocumented migrant farm workers already here “living in our communities and harvesting the food that we eat.” Next, he adds, Congress needs to replace H-2A with a new guest worker program “that is going to be more flexible and more cost effective.”

Little calls for a new worker program “that allows us to replace the current farm workers that we legalize when they either age out or move on to other jobs.”

Sábor Farms ranch manager Richard Bianchi, raising 2,000 acres of cilantro and other leafy greens in California’s Salinas Valley, tells Agri-Pulse that using about 100 H-2A workers is vital to his operations, to replace the undocumented migrant workers he previously relied on.

Facing the increasing labor shortage, Bianchi says automation is essential because “We’re all trying to do anything we can do to get away from any type of hand labor.” He sees the solution as first, “giving our existing work force some type of legal status. You’ve got to take care of these people because they’re productive people we all grew up with.” Second, he calls for a more workable guest worker program that brings in new migrants to replace those who’ve aged out, left for other jobs or can no longer make it across an increasingly sealed border.

Nov. 2018’s USDA Economic Research Service report Farm Labor Markets in the United States and Mexico Pose Challenges for U.S. Agriculture points to more problems ahead. It concludes that with the Mexican economy improving, “rural Mexicans are less likely to work as farmworkers either in Mexico or in the United States.” It adds that overall, “The U.S. farm labor market shows many signs of tightening, including producer reports of labor shortages, increases in farm wages, more employment of guest workers through the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program, and a shrinking supply of farm labor from rural Mexico.”

One potential answer comes from the Agricultural Worker Program Act (S.175 and H.R.641) introduced in January by California Democrats Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Rep. Zoe Lofgren along with 13 Senate co-sponsors and 73 House co-sponsors. The bill would provide immediate legal “blue card” eligibility for established migrant farm workers to continue working in the U.S., along with a pathway to longer-term permanent residency and possible citizenship for these workers and their families.

Tom Nassif, president and CEO of the Western Growers Association that represents fresh fruit, produce and tree nut growers, packers and shippers, has challenged Congress directly. Testifying in in the House Judiciary hearing April 3, he pointed to a Texas A&M report showing that 77 percent of U.S. vegetable farmers have scaled back operations in response to labor shortages and that more than 80,000 acres of fresh produce once grown in California have moved to other countries.

Nassif said it’s clear the fruits and vegetables eaten in the U.S. “will be harvested by foreign hands” and Congress must decide “do you want those foreign hands harvesting your fruits and vegetables to be on farms here in the United States or do you want to see production continue to shift to farms in foreign countries?”

At this point, the sense the urgency that farmers and ranchers feel on a daily basis is still missing in Washington. A handful of GOP Senators met with Kushner and other White House staff on Tuesday to discuss his soon-to-be released plan for immigration reform. Sen. Kevin Cramer, R-N.D., told Agri-Pulse there was no discussion of guestworker programs - instead, the meeting was focused on border security and reforming legal immigration.

"H-2A reform would not be part of this initial reform plan," said Sen. David Purdue, R- Ga. "Visa programs are too big of an issue for this bill."

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com