The timing and substance of the next COVID-19 relief bill may hinge on the issue of liability.

Republicans including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy are insisting on a “shield” to protect businesses from civil lawsuits, but Democrats are pushing back.

McConnell says House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is “ignoring” what he calls the “second pandemic — an avalanche of lawsuits that is waiting to greet” businesses as they reopen. But Pelosi said last week she and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer “would not be inclined to be supporting any immunity from liability.”

A wide range of business groups, including many in the food industry, say they need the protections in order to operate without fear of future lawsuits. In an April 14 letter to McConnell, dozens of groups, including the North American Meat Institute, American Bakers Association, FMI, The Food Industry Association, the National Cotton Council and United Fresh Produce Association, pointed to the existence of state and federal “good Samaritan” laws to protect businesses from lawsuits.

“These protections cover individuals as well as corporations, such as airlines and vaccine manufacturers that help protect passengers or customers in need,” the groups said. “During the COVID-19 crisis, businesses that make up the nation’s essential critical infrastructure are acting as good Samaritans. They are serving the real, immediate needs of the American people and they should not have to worry they will be sued for simply providing the products and services Americans need right now.”

“We really want to prevent the wave of coronavirus exposure litigation from crashing onto the family farmers,” says Jason Resnick, vice president and general counsel of Western Growers, which represents produce growers in Arizona, California, Colorado and New Mexico. His group signed on to a letter to California Gov. Gavin Newsom asking him “to expand the Emergency Services Act, which protects private entities from civil liability during times of crisis, to include all industry sectors that are providing ‘critical goods, services and facilities’ during the pandemic.”

Jason Resnick, Western Growers

Resnick tells Agri-Pulse that Western Growers’ members “are doing everything they can to keep their employees safe,” including use of social distancing and better sanitation, but “that doesn’t stop the plaintiffs’ attorneys who are circling, waiting for employees or others to get sick from this worldwide pandemic and blame it on an employers.”

Asked whether growers have been slow to adopt protections for workers, Resnick says it’s been just the opposite — they have “very rapidly embraced” evolving federal guidelines as they have been issued.

Offering a different perspective, however, are worker advocates such as Alexis Guild at Farmworker Justice, who said on a press call last week, “We are hearing from workers that many employers are not following” CDC guidelines.

Farmworkers “tend to lack adequate access to hand-washing stations in the field,” she says. “They are not necessarily provided protective equipment and often live in crowded and substandard housing.”

Her group supports an Essential Workers Bill of Rights for inclusion in the next COVID-19 relief bill, whose timing is uncertain, in part because of the liability disagreement.

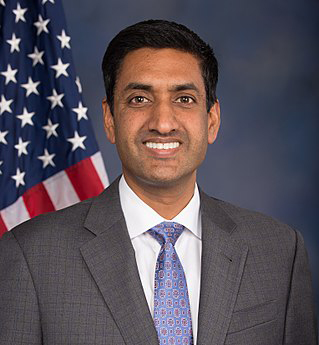

“You can’t have liability protection for business without assuring that workers are treated safely and that the conditions are safe,” Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., told reporters last week. “My argument would be to McConnell if you want safe harbors for business to reopen and not have the threat of extreme liability, then you have to adopt the workers’ bill of rights.”

Proposed by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Khanna, the worker’s bill of rights says “CEOs should be required to personally certify they are in compliance with worker protections, so they can face civil and criminal penalties if they break their word,” according to a summary of the proposal.

The liability issue gathered steam with comments made by President Donald Trump before he signed an Executive Order designed to keep meat and poultry plants operating. Trump said the E.O. would “solve any liability problems” those companies are facing.

Issued using the authority of the Defense Production Act, the E.O. “clarifies which safety standards companies must follow — those found in the joint guidance from the CDC and OSHA,” says a USDA spokesperson. “There will be no longer conflicting guidance coming from state and local officials. By clarifying the standard they must meet, companies subject to the order may take the actions called for in the joint CDC/OSHA guidance and thereby reduce their risk of being found legally liable.”

Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif.

The guidance from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests a number of actions meat and poultry plants can take to reduce the chances workers will contract or spread COVID-19, including modifying production processes, increasing sanitation efforts and placing plexiglass barriers between workers on the lines.

A subsequent enforcement memo from Department of Labor Solicitor Kate O’Scannlain and Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for OSHA Loren Sweatt says “because of the President’s invocation of the DPA, no part of the Joint Meat Processing Guidance should be construed to indicate that state and local authorities may direct a meat and poultry processing facility to close, to remain closed, or to operate in accordance with procedures other than those provided for in this guidance.”

OSHA said it would consider supporting businesses in court if they demonstrate “good faith attempts” to comply with the guidance but are sued for workplace exposures.

“Likewise, the Department of Labor will consider similar requests by workers if their employer has not taken steps in good faith” to follow the guidance, the memo says.

In a report issued Friday, May 1, the Congressional Research Service said the Defense Production Act includes language limiting liability for companies complying with the DPA. But is not a “blanket grant of immunity from liability for all actions that an entity may take under a DPA order.”

“While an entity may raise a DPA order as a defense if sued for actions taken while complying with that order, whether that entity will ultimately be granted immunity by a court is a fact-specific inquiry,” CRS said.

Lisa Mankofsky, litigation director at the Center for Science on the Public Interest, says a liability shield would simply incentivize “bad behavior” and would be “counterproductive to businesses staying open."

In a letter to congressional leaders, CSPI said “state tort law already provides companies with sufficient legal protection and takes into account the context in which any potentially tortious act occurs.” Generally speaking, “to bring a successful tort lawsuit, employees or customers would need to prove that a company’s negligent conduct caused them to contract COVID-19.”

Mankofsky said the “smart thing to do” for businesses would be to comply with the federal guidance.

Western Growers’ Resnick said a liability shield “should not incentivize bad behavior,” which he said “should never be condoned.” However, “that’s not the intent of the shield.” If employers are following federal guidance, “they should not also be subject to civil litigation.”

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

Resnick says “there’s a lot of dispute about what negligence means in this environment.” Businesses that have engaged in grossly negligent conduct “should be held accountable,” but “once you start getting below that line, the question of where the negligence line is drawn becomes much more murky.”

Alex Tomaszczuk, an attorney at the Pillsbury law firm who specializes in government contracting, said he believes the DPA "pre-empts state and local law if it is inconsistent with the federal statute."

However, he added, "as a practical matter, it is in the interest of the federal government to cooperate with local and state authorities."

Jonathan Pomerance, an attorney who focuses on government contract matters at PilieroMazza in Washington, D.C., said “The Defense Production Act does not provide the president or USDA with the authority to preempt state and local workplace health and safety laws. All the DPA does is allow the government to direct plants to prioritize the production of certain items, and allocate the distribution of those items.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.