This is the fifth and final installment of our series,“Agriculture’s sustainable future: Feeding more while using less.” Part Four looked at the potential for technological innovations to make a significant impact on U.S. agriculture's environmental footprint. The full series is available here.

U.S. farmers have watched for years as Brazil has become an agricultural powerhouse, grabbing increasing market share in soybeans, cotton, beef and other commodities by converting its vast rainforests and savanna into cropland, with plans to expand even more over the coming decade.

Another U.S. competitor, Argentina, has grown its grain production in part by breaking up its Pampas grasslands, a practice that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile, U.S. agriculture groups have been struggling to address demands by policymakers and major multinational corporate customers to cut U.S. farmers’ environmental footprint. Now, those groups are hoping the progress producers are making and the work done to document it will pay off in a competitive advantage for U.S. ag exports in the lucrative European and Asian markets.

One reason it might be a good bet, say experts, is the European Union’s new Green Deal, a sweeping set of proposals that include new metrics for agricultural sustainability. Among other things, the EU document calls for measures to curb the sale of agricultural products “associated with deforestation or forest degradation.”

Marty Matlock, a University of Arkansas scientist who advises sustainability programs for numerous U.S. farm commodities, believes that U.S. farmers should have “a significant competitive advantage” against Brazil and Argentina at least when it comes to selling soybeans, corn and beef into the EU, a market of 440 million consumers.

“We have spent the last 15 years developing and documenting our sustainability initiatives that are multi-stakeholder. validated by external parties, have the oversight of our conservation organizations, and the engagement of our conservation organizations, who are also active in Europe,” he said.

Some of the same farming practices, such as conservation tillage and cover crops, that are being sold to U.S. farmers as ways to improve soil health, reduce runoff and potentially make them eligible for carbon credits could also help compete in foreign markets: Scientists are working to produce data that will assure markets and policymakers that those carbon-conserving practices reduce the environmental footprint of animal feed and the meat and dairy products the feed is used to produce.

For example, the National Cotton Council launched a nationwide initiative in September to set a new standard for sustainably-grown cotton. The U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol “brings quantifiable and verifiable goals and measurement to sustainable cotton production and drives continuous improvement in key sustainability metrics, thereby giving brands and retailers the assurances they need for their supply chain,” says NCC spokeswoman Marjory Walker.

To be sure, the EU rules have raised alarms within the Trump administration because of their potential to discourage the use of genetically engineered crops and pesticides. A recent study by USDA’s Economic Research Service has estimated that the Green Deal strategy will result in lowering Europe’s agricultural production by 12%.

The Green Deal "Farm to Fork" strategy goes so far as to suggest replacing some traditional feed sources, such as "soya grown on deforested land," with alternatives such as insects, algae and fish waste.

The standards that exporters will have to follow to keep selling into the EU market are still a moving target, too. An executive with the European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation told Agri-Pulse in an exclusive interview that U.S. soybean exporters will likely be required to tighten their sustainability standards.

But Jim Sutter, CEO of the U.S. Soybean Export Council, believes that U.S. soybeans should benefit from the global sustainability push simply because it isn’t grown on deforested land. He said, “Our soy has a great track record from an environmental perspective and from a sustainability perspective.”

Brazil accused of backtracking under Bolsonaro

Brazil used its conversion of forest and grasslands to challenge the United States as the globe's biggest producer of soybeans, surpassing the U.S. in both 2017 and 2019. Brazil now has some of the world’s strictest land-use laws on the books, calling for the preservation of about 66% of its land to native vegetation while the country spends hundreds of millions of dollars to promote carbon sequestration, soil restoration and water conservation, but the country is still often viewed an environmental liability.

Brazilian farmers are required by law to leave between 20% and 80% of their land uncultivated, and agribusinesses there have voluntarily agreed not to source commodities from deforested rainforest. The government is working to improve soil conditions on millions of acres of land through public programs like the Low Carbon Emission Agriculture and Recovery of Degraded Pastures plans.

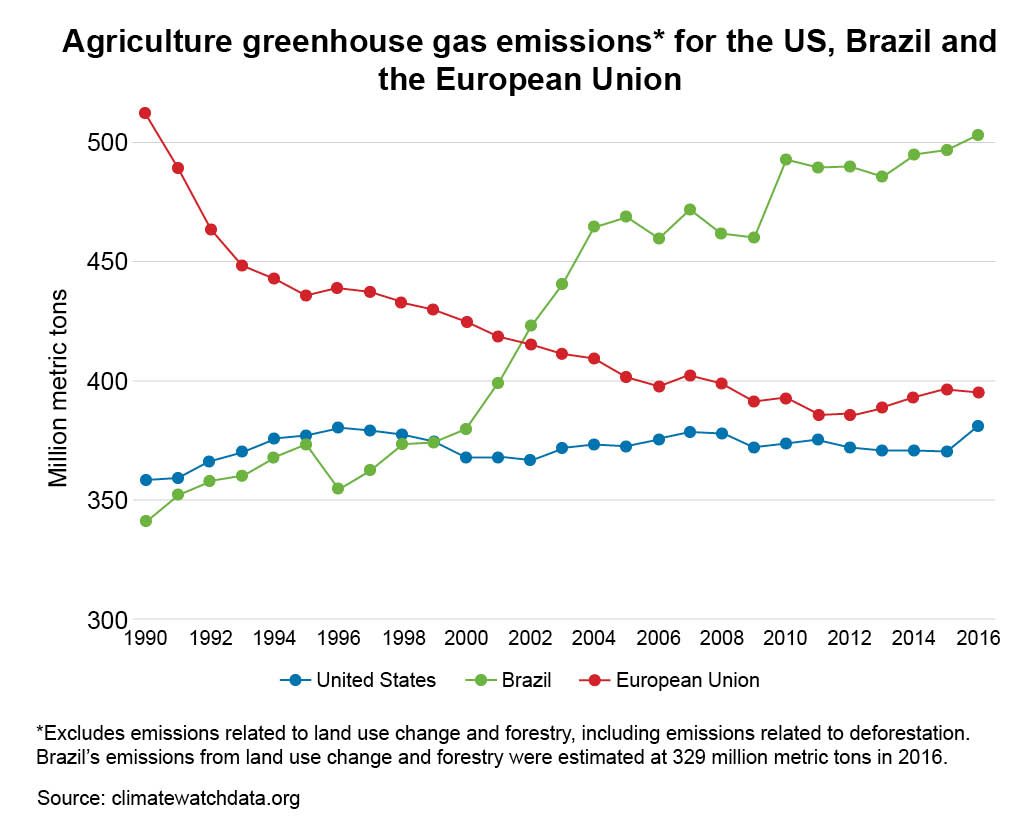

Still, Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions are large and growing. In 2016, the country produced 1.4 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, including 503 million metric tons from agricultural production alone, according to ClimateWatch, a database managed by the World Resources Institute.

Another 329 million metric tons occurred because of the conversion of grasslands, and destruction of forests.

Argentina had 128 million metric tons emissions from agricultural production in 2016, plus 102 million metric tons from land use change and deforestation.

By comparison, EU and U.S. ag emissions totaled 395 million metric tons and 381 million metric tons respectively, and both the EU and U.S. are net negative when it comes to conversion of grasslands or forests, according to ClimateWatch.

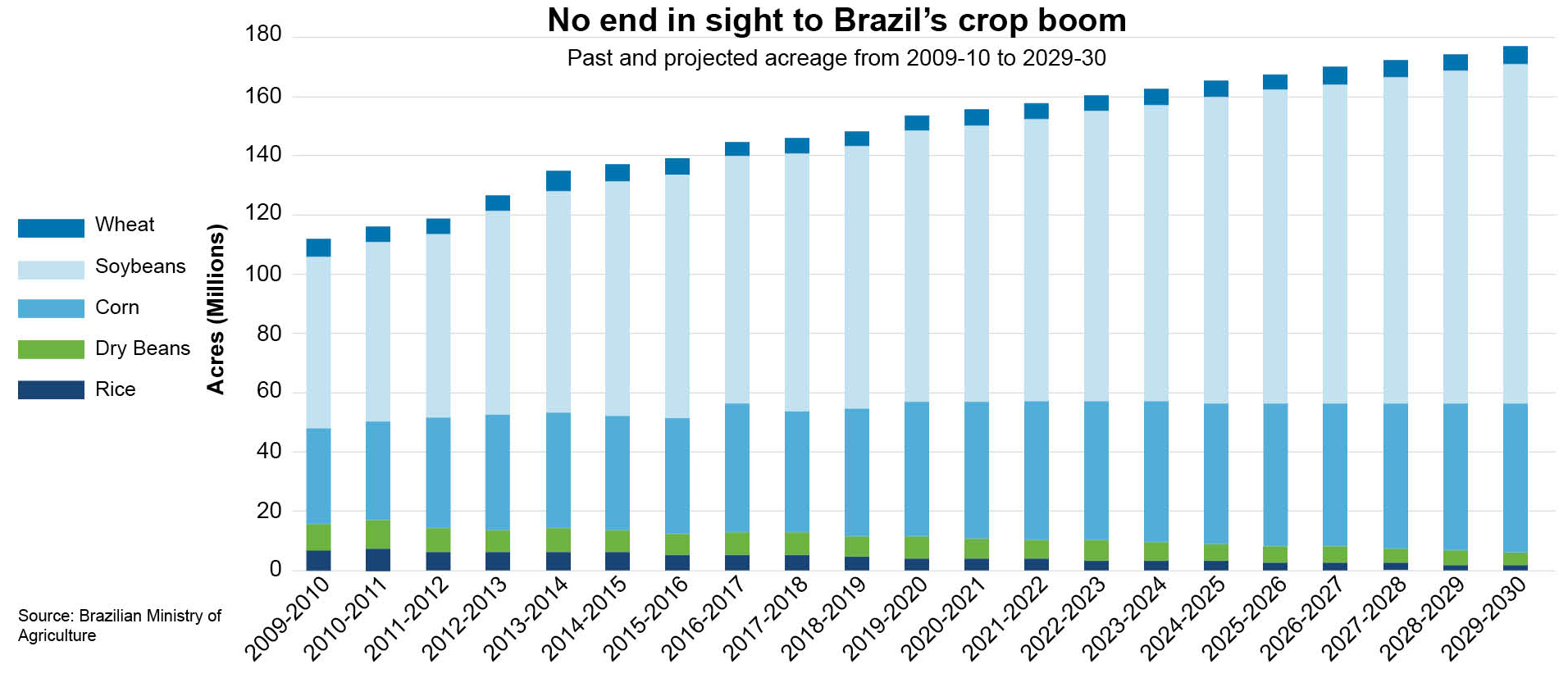

Brazil’s ag emissions are likely to keep growing. Farmers there are expected to increase their plantings of five major crops, soybeans, corn, wheat, dry beans and rice, by 16% over the next decade to 178 million acres, up from 153 million acres last year.

Meanwhile, the Climate Observatory, a Brazilian environmental advocacy group estimates that Brazil’s carbon may have grown by as much as 20% this year from 2018 “depending on the trajectory of the deforestation in the Amazon in the coming months and time for the economy to start recovering,”

Brazil’s environmental reputation took another major hit recently when Vice President Hamilton Mourão unveiled new satellite data that showed the destruction of about 11,000 square kilometers of Amazon rain forest this year – a 9.6% increase from last year.

It’s the highest level of deforestation since 2008, according to data maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation. Mourão tried to downplay the new data, stressing that the rate of increase in deforestation has been higher in recent years, but the negative backlash, domestically and internationally, was immediate.

Carlos Rittl, a senior fellow at the German Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, proclaimed President Jair Bolsonaro’s “great achievement when it comes to the environment has been this tragic destruction of forests, which has turned Brazil into perhaps one of the greatest enemies of the global environment and an international pariah too.”

Not much thought would have been given to the situation twenty years ago. The annual accounting of Amazon deforestation rarely made the front pages of newspapers. But that’s changed as feed and food companies around the world are increasingly concerned about the widening awareness of climate change as consumers increasingly demand their food is sustainably produced.

Brazilian officials argue that much of the country’s increase in crop acreage these days comes from the conversion of cattle grazing land into soybean fields.

“If we only use the pasture that’s underdeveloped and under-used, that would be enough for us to expand our production harmlessly,” one official told Agri-Pulse.

But breaking up grasslands for crops releases carbon into the atmosphere and deforested land is being turned into ag production, even though the process can take years and the government is trying to verify land deeds.

“It is key to continue focusing on landholding regularization,” the official said. “If it is clear who owns the land, authorities can enforce the law more effectively."

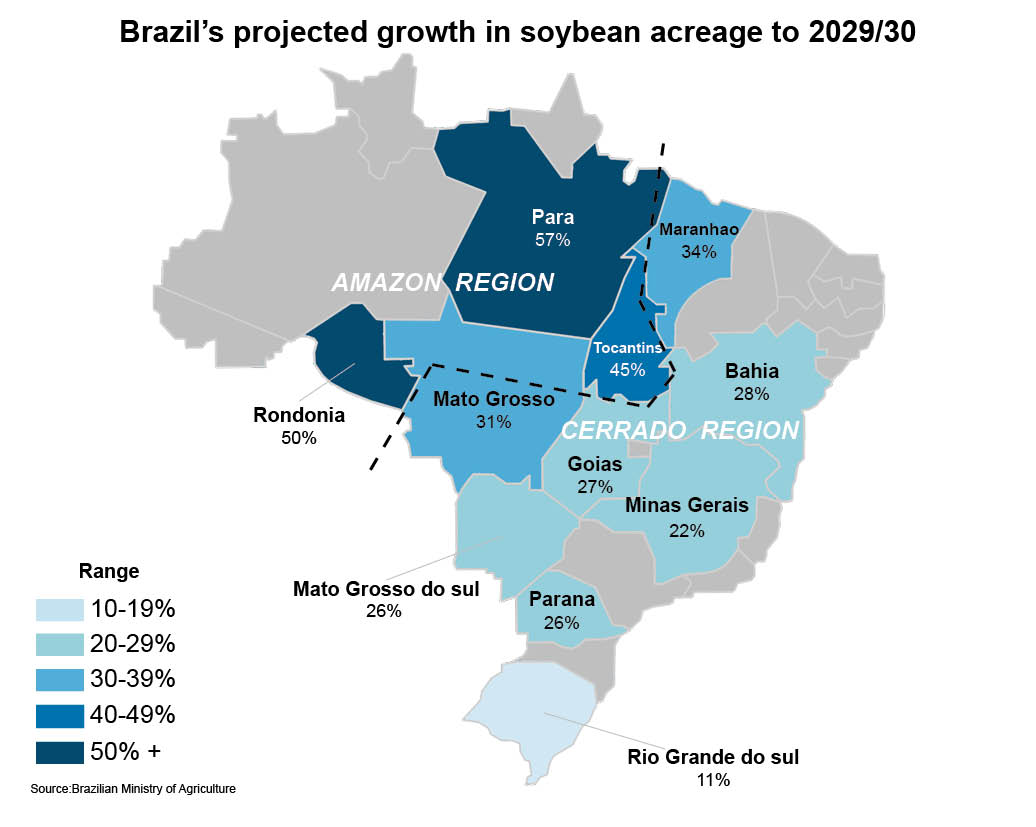

While most of the acreage expansion is indeed expected to occur on pasture land that is no longer being used to graze cattle – that’s especially true in Mato Grosso – much of the expansion will also be realized by the “clearing of new land for production” in states like Maranhao, Tocantins, Piaui, and Bahia, according to a recent report by the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service.

Spying by satellite to stop deforestation

The Bolsonaro administration is scrambling to convince the world that consuming Brazilian crops isn’t damaging the planet. As part of that effort, Brazilian Agriculture Minister Teresa Cristina accompanied representatives from South Africa, Spain, Peru, Colombia, Canada, Sweden, Germany, the European Union, United Kingdom, France and Portugal to three cities in the state of Amazonas to witness how responsible farming can be conducted alongside the rainforest and without damaging the ecosystem.

"The initiative aims to show the national and international community that the Brazilian Amazon remains preserved and that its environmental and human complexity does not allow a general understanding of the region,” she said. “Knowing is the basis for understanding and suggesting actions to contribute to the sustainable development of the region - preserving, protecting and developing our immense tropical forest."

But it’s an uphill battle as the government tries to contend with a legal morass of property rights in a web of states that are home to parts of the vast Amazon forest.

Millions of acres of rain forest burn or are cut down every year. That’s when land-owners move in to try to make a profit.

“You’ve got the logger that goes first, then along comes the cattle rancher and the cycle evolves until eventually there are soybeans where there used to be cows,” says Kory Melby, owner of the Brazilian Ag Consulting Service in the state of Goiás.

Admitting that the problem exists, the Brazilian government is warning lumber harvesters and cattle ranchers that they won’t get away with clear-cutting and using land that the government is trying to protect.

|

Sustainability measurements, data availability vary by country Foreign markets for U.S. farm commodities are changing rapidly as consumers increasingly want to know if the food they eat is sustainably sourced. That requires more documentation that the production methods aren’t contributing to deforestation and global warming. But the sustainability expectations don’t stop there. They include details on dozens of other metrics like fair pay, biodiversity, food waste and nutrition. Unfortunately, uniform data is not available in every country and some experts question whether you can accurately compare sustainable production measurements around the globe. Indicators also are used to compare countries and to track progress in a particular country. One study published in the journal Nature developed food system sustainability scores for countries based on 27 different indicators from agricultural emissions to water usage, food supply variability, food waste and obesity. |

“Before, it wasn’t easy to know who was destroying the Amazon, but now the (government) uses satellite technology to monitor the region, identifying and providing evidence to penalize the people responsible for illegal deforestation,” the government says in a slick, computer-animated film posted on the internet.

The film shows loggers cutting down trees and ranchers grazing cattle in the forest as greedy businessmen skulk in the background, only to be spotted and targeted by cameras above them. A narrator warns: “Whoever destroys the Amazon won’t be able to hide from the government.”

Representatives of the Brazilian ag sector downplay the significance of farms on deforested lands as a very small minority among the vast majority of responsible and legal producers, but the stain they leave on all Brazilian farmers – legal or not – presents a real and potentially long-term problem, says Marcello Brito, president of the board of directors of the Brazilian Agribusiness Association.

Farmers don’t need to produce in Amazon forest regions to be penalized for the actions of farmers that do, he said in a recent blog post. Importers often don’t know about the region, but just the nation it comes from.

“We have always been among the top three or five in the leadership of environmental processes in the world,” he said. “However, today, Brazil is not part of any international commission that determines the socio-environmental future of the world. As we already had this leadership, we need to recover it.”

While it is unclear how much acreage in Brazilian rainforest has been converted into farm land, Bunge, a participant in a voluntary moratorium on sourcing soybeans from the deforested Amazon biome, calculates that 273 farms are blocked from commerce.

Perhaps the biggest reason international buyers keep purchasing soybeans and other commodities from Brazil is the Brazilian Soy Moratorium, a voluntary agreement by trading firms not to buy or sell soybeans produced in Amazon land that was deforested after July 2008.

While burned out and clear-cut remnants of the Amazon may get most of the public attention, the “conversion” of Brazil’s ecologically diverse grasslands – the Cerrado – is also a major concern for environmentalists and there is a move to add farms that destroy the protected savanna land to the Moratorium.

It’s a controversial topic because the vast grasslands are also home to nearly half of the country’s farms and pastures.

Grain traders say they're trying to protect Amazon

It’s a fact that companies like Bunge Ltd. and Archer Daniels Midland Co., with operations in South America. have been well aware of long before the latest government release on Amazon deforestation.

For nearly a decade Bunge has been weeding out farms in its South American supply chains that grow their crops on land that has been deforested or converted to growing fields from wetlands.

As part of its corporate climate commitments, Bunge Ltd. has pledged to "achieve deforestation-free supply worldwide between 2020-2025, considering both direct and indirect sourcing.”

The issue of converting environmentally sensitive land into production has become increasingly important to European feed makers, according to Alexander Döring, secretary general of the European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation, or FEFAC.

Focusing on Brazil’s highly environmentally sensitive lands in the savannas, grain trading giant Bunge announced in November that it has reached a 95% success rate in assuring that the crops it contracts come from “deforestation-free value chains.”

"Our commitment to non-deforestation is among the highest priorities for our company and our entire industry," said Rob Coviello, the vice president for sustainability at Bunge.

Rob Coviello, Bunge

“Our progress towards these goals is indicative of our continued collaboration with local producers, in the field, in South America, as well as a greater focus on working with partners to create innovative solutions and make our sector reach supply chains free from deforestation.”

Cerrado lands, besides being the home to jaguars, anteaters, armadillos and other exotic animals, also make up the largest farming region in Brazil, where more than 50% of the country’s soybeans, 80% of its cotton and 40% of its corn are grown in states like Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul and Goiás.

There are wooded areas, wetlands, but “nearly half of the biome’s native vegetation has been lost” due to “robust economic activity,” according to an analysis by the Soft Commodities Forum, a global alliance formed by some of the world’s largest agricultural commodity trading companies. They include Bunge, Cargill, Glencore, Louis Dreyfus and China’s COFCO.

“The Cerrado region of Brazil plays a significant role globally for both people and nature, including climate change mitigation, biodiversity, and freshwater systems,” the companies said in their latest joint release that was published by ADM and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

“However, the extent and pace of native vegetation loss resulting from agricultural expansion in the Cerrado poses a significant threat to these social, environmental and economic values.”

More than 70% of the soybeans sourced by ADM in South America are grown in Brazil and the company started up its “no deforestation” effort in 2015 to eventually certify that all of its soybean supply chain would be free from the taint of deforestation through intense monitoring and traceability programs.

By 2018, the company began using digital satellite farm maps to certify that its suppliers were not tearing up sensitive lands. About 40% of the soybeans ADM sources from Brazil are grown in the Cerrado and it is now directly monitoring roughly 90% of those farms.

US farmers try to sell sustainability to the EU

Thousands of miles to the north, American farmers are largely content with the results of years of work to show the world that U.S. farms are some of the most sustainable operations on the globe and that U.S. farmers are already some of the most conscientious caretakers. For almost 40 years, the majority of U.S. farmers have adhered to conservation compliance rules, which require producers to meet minimum levels of conservation on highly erodible land and not to convert wetlands to crop production – if they want to be eligible for USDA program payments.

“Since the early 1900s, forest land in the United States has remained pretty stable,” USSEC's Sutter told Agri-Pulse. “Actually, according to USDA statistics, between 1982 and 2015, we’ve actually increased the number of acres of forest land in the U.S. by 5 million acres. Since 1982, we have also seen a decrease in crop land by just over 50 million acres.”

As far as land use is concerned, this means that domestic and international feed and food producers don’t have to worry that U.S. soy is contributing to the degradation of the environment, says Sutter.

Jim Sutter, USSEC

But even though that may seem obvious to farmers in the U.S., exporters that depend on marketing soy products to the rest of the world need proof to show buyers from Lisbon to Tokyo, said Sutter. So, the council set out to arm exporters with data.

The stability of land use, along with documented use of cover crops, no-till farming, grass waterways and buffer strips to reduce water usage, prevent soil erosion and lower energy consumption, allowed USSEC to launch the U.S. Soy Sustainability Assurance Protocol in 2013.

“We started hearing a lot of talk about people around the world becoming very concerned about the sustainability of the soy they were using, particularly out of Europe,” Sutter said. “We put together a group of stakeholders – people who bought soy in Europe and Asia as well as NGOs and we created the Soy Sustainability Assurance Protocol, or SSAP for short.”

The goal, Sutter said, was to offer evidence to buyers in some of the most environmentally conscientious countries in the world that U.S. soy will allow them to make sustainability claims on the products they produce with the imported oilseed products.

One of the toughest hurdles was Europe’s FEFAC, which incorporates 24 separate associations in 23 EU countries as well as Switzerland, Turkey, Serbia, Russia and Norway.

After hiring an independent contractor to compare the U.S. program to all of the sustainability demands of the European feed manufacturers, FEFAC accepted the certification as a method of verifying sustainability, Sutter said. Even the Tokyo Olympics Commission examined the SSAP and announced its support of the program to certify sustainably produced soy oil and tofu.

“I do know that American soybeans are highly valued in the European feed industry,” said Roger Gilbert, publisher of the International Milling and Grain Directory. He said the European feed federation’s approval of the U.S. soy protocol puts American producers in a “good position.”

There is even a rising clamor for sustainably produced soy in China, said Sutter. “There’s growing interest among consumers to know that the soy oil they are buying is sustainably produced. It’s a small segment, but it’s a growing one.”

The demand elsewhere around the globe is already mature, according to U.S. Soybean Export Council data. Back in 2014 the U.S. exported 6,845 tons of soybeans that were verified under SSAP. Five years later, SSAP was used to prove the sustainability of 21.3 million tons of exported soybeans – about 36% of all the international shipments in the 2019-20 marketing year.

“The demand for verified sustainable U.S. soy exports has continued to grow since the SSAP’s development,” says Abby Rinne, USSEC’s sustainability director. “It’s clear that sustainability is top of mind for our buyers.”

But if America’s soybean farmers want to continue to use the SSAP to sell to Europe’s largest feed makers, USSEC is likely going to have to revamp it.

FEFAC’s Döring tells Agri-Pulse that the organization is planning to strengthen its list of sustainability requirements and that means the SSAP will have to again undergo a second review by the International Trade Council, an offshoot of the World Trade Organization in Geneva.

“We are currently upgrading the program,” Döring said. “We expect our board to adopt a revised list of criteria of our soy sourcing guidelines. The revised set of guidelines will cover a new set of criteria, including no conversion, no deforestation, which are very important for the European market. Then we will invite SSAP and other programs to do a second round of benchmarking sometime beginning next year. It’s part of a continuous improvement program.”

FEFAC is expected to make that announcement soon.

The FEFAC decision to upgrade is not a result of the EU’s proposed Green Deal overhaul of agricultural production methods, says Döring. In fact, he stressed that he does not believe that the Green Deal will hurt the ability of U.S. exporters to sell feed ingredients to their European clients.

Most of the impact will likely be on the European corporations, requiring tighter reporting requirements on where they source their soy and corn.

“There is a strong commitment in the EU to ensure that food security remains in place and global trade continues as part of the solution,” he said. “I know there’s anxiety out there on the Green Deal impact … but I don’t think this will have any immediate, direct implication on existing trade patterns.”

Still, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding exactly how the European Green Deal will impact agricultural exports to the trading bloc.

“Thus far the Green Deal has put forward some targets, however, there has not been agreement upon the strategy to achieve the goals,” Rinne said.

“We believe the U.S. soy industry continues to demonstrate our commitment to sustainability through the U.S. Soy Sustainability Assurance Protocol. We look forward to engaging with the EU in addressing the challenges facing the world and how agriculture can be a solution.”

Further complicating the trade outlook is the EU’s proposal of a carbon border adjustment tax on imports from countries deemed to have excessive carbon emissions. Under the Green Deal, EU farmers will have to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, so foreign producers that export to Europe should either bear the same burdens or pay a tax to compensate, the theory goes.

The carbon tax is still in the proposal phase and details have not been released.

The Belgium-based European Corn Federation and the France-based General Association of Corn Producers both say they want the tax to weigh heavily on competing grain imports.

“It appears to be a threat if the EU does not take into account the economic and sectoral effects of its carbon policy compared to those carried out by its international competitors,” the groups said in identical submissions to the European Commission. “The EU’s low carbon approach will indeed create differences between European and third country production systems if the latter countries do not make the same efforts.”

Fertilizers Europe says it backs “a model whereby the actual carbon intensity of imported products is subject to costs equal to those borne by EU producers.”

If the EU goes in that direction with the tax, Brazilian soybean, corn and meat exports may be hit hard. In 2011, Brazilian greenhouse gas emissions from land conversion and agricultural production dropped and stabilized over the next several years, according to the World Resources Institute.

Other growers face sustainability standards, too

The same climate concerns that are driving the concerns of soybean growers in Brazil and U.S. also are spurring efforts in many other sectors, including cotton, dairy, beef and pork.

European-based food giants such as Danone and Nestle are backing the EU’s move to slash greenhouse gas emissions at the same time they are increasing pressure on dairy producers in the United States to shrink their carbon footprint.

Executives of Danone and Nestle were among 170 business leaders who signed a statement in September calling on EU heads of state to support the Green Deal’s target of reducing emissions 55% by 2030. The EU’s goal is to become carbon neutral by 2050.

The U.S. dairy industry announced earlier this year that it would work toward becoming carbon neutral by 2050, and in October, Nestle announced that it was committing $10 million toward reaching the goal. Dairy industry officials say that it’s a collective goal; not all farms are expected to zero out their emissions.

The Green Deal and rising demand from textile and apparel companies around the globe for sustainably sourced products is also spurring cotton farmers from Texas to Brazil's Mato Grosso to adopt a wide array of environmental standards that can be measured and verified.

The U.S. cotton sector kicked off its U.S. Trust Protocol this summer, challenging farmers to over the next five years to reduce land use by 13%, decrease soil carbon release by 30%, reduce soil loss by 50%, reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 39% and reduce energy consumption by 15%.

After a pilot program, the Protocol launched on Sept. 22 and 500 farmers have already signed up. Feb. 28 is the end of the first wave of the 2020 enrollment campaign and the National Cotton Council's Marjory Walker says the goal is to sign up between 750 and 1,000 producers.

By 2025, the cotton council hopes to get at least half of the roughly 16,000 U.S. cotton farmers to join.

“Consumers want more transparency when it comes to the products they purchase and the European Union is threatening brands and retailers with stricter regulations when it comes to sustainability reporting and the responsible sourcing of raw materials,” says Gary Adams, president and CEO of the National Cotton Council. “These evolving dynamics prompted the creation of a new sustainability standard for cotton and the launching of the U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol.”

Outside the U.S., the Geneva-based Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), is leading the international effort by textile and apparel companies to incentivize farmers in Brazil, China, India, Egypt, Australia, Turkey, South Africa, Pakistan and elsewhere to commit to verifiable sustainable practices under the organization’s Better Cotton Standard System.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse.

The Brazilian Association of Cotton Producers, or ABRAPA, became a BCI partner in 2010 and by 2014, the group succeeded in completing a sustainable verification program that BCI accepted as equivalent to its own.

Last year, several hundred Brazilian farms produced cotton under the BCI program on 2.8 million acres, according to the organization. Brazilian farmers planted about 4.1 million acres of cotton in 2019.

But the National Cotton Council is expecting its sustainability program will give U.S. farmers an edge over foreign competitors, Walker said.

“Because the U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol will collect quantifiable data on farming practices and the associated environmental footprint, we believe the program provides the textile supply chain with information not available for other countries,” she noted. “As major brands and retailers set targets for sustainable sourcing, we believe the U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol will help ensure that U.S. cotton has access to those markets.”

Another sector where U.S. and South American producers compete is in beef, and Matlock of the University of Arkansas thinks that the deforestation, grassland conversion and destruction of wildlife habitat in Brazil and Argentina should give American ranchers an edge in export markets. The industry-based U.S. Roundtable for Sustainable Beef is trying to document how the American industry lines up with the Green Deal goals on key performance indicators, he said.

The science shows Europeans should "buy beef from the United States rather than from Brazil," where much of its cattle are grazed in the southwestern part of country "on the edge of forest or in the middle of recently burned down forest or converted grasslands," said Matlock.

Andrew Walmsley, a director at the American Farm Bureau Federation, said most American farmers "have already plowed a pretty big path towards sustainability. Obviously this is going to continue to be a focus and challenge with trade, but a lot of it is being able to measure the progress we’ve made. We don’t want to go completely European with our production practices.”

Still, there are a lot of benefits for farmers that improve their sustainability with climate-friendly farm practices, says Jenny Hopkinson, a senior government relations representative for National Farmers Union. Farmers will have more options on where they can sell their crops and sustainable practices are just good for the land and the environment.

But the onus should not just be on farmers, she stressed.

“We don’t want to see unfunded mandates coming down from companies, saying you have to do X, Y and Z without providing the resources to do those things, because it’s certainly not cheap to do,” Hopkinson told Agri-Pulse. “In general, if the resources and technical assistance are there, making these changes have long-term benefits.”

EU standards add to Brazilian soy struggles

Still, European demands may further complicate the disjointed efforts by Brazilian farmers and agribusinesses to prove that the crops coming from Brazil are sustainably sourced.

Unlike the uniform soy protocol that can be used by nearly every U.S. soybean farmer, there are several sustainable and environmental verification programs operating in Brazil, covering farmers in different regions. One of the most dependable, Döring said is run by COAMO, a cooperative that includes mostly soybean farmers in the southern states of Paraná and Santa Catarina, as well as Mato Grosso do Sul.

There are also verification programs run by individual processing and trading companies like ADM, but perhaps the most comprehensive effort to date is “Soja Plus,” that has been launched in five states that ARE home to some of the most environmentally sensitive and protected lands in Brazil: Mato Grosso, Goiás, Bahia, Minas Gerais and Mato Grosso do Sul.

Sponsors of the effort include Bunge, ADM, Cargill, the Bank of Brazil, Amaggi and the Nature Conservancy.

“This is a farmer-owned program and the largest of its kind in Brazil,” said Döring, “but it’s still a work in progress.”

Early on, the Brazilian Soy Moratorium was hailed as wildly successful by the companies that made it possible. Deforestation rates were dropping sharply - down 80% in the first six years. But that trend has reversed in recent years and Brazilian government officials have become increasingly defensive.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and President Donald Trump during a 2019 meeting at the White House.

In his 2018 book, Shades of Green, Sustainable Agriculture in Brazil – a copy of which was given to Agri-Pulse by former Brazilian Agriculture Minister Blairo Maggi - Evaristo de Miranda, does not take long to blame foreign countries for maligning Brazil’s farming sector.

“Abroad, competitors and even clients have been showing and cultivating a false, negative image of Brazil’s agriculture for years in order to obtain price and market advantages,” writes de Miranda, a researcher with the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, or EMBRAPA.

“Producers of meat and grains from other countries accuse Brazilian cattle ranching and soybean production of clearing the Amazon and Cerrado. And they compete for the same national product markets. To many, both here and abroad, Brazil’s farming devours native vegetation and makes it its main input, with enormous negative impact on soil, water, biodiversity and public health.”

|

U.S. producers have a long history of soil conservation, greenhouse gas reduction The U.S. already has an advantage because producers here have a history of leading the way in practices such as no-till or minimum-till farming that sharply reduce the release of greenhouse gasses from the soil, says USDA Under Secretary for Trade Ted McKinney. “Some of the elements of Farm to Fork, the U.S. began adopting many years ago,” said McKinney, speaking about a section of the EU’s Green Deal. The USDA has been encouraging farmers to conserve soil for more than 80 years, a message USSEC says producers have taken to heart in order to pass their land “to the next generation in even better condition than they received it.” The Dutch firm Blonk Consultants confirmed for USSEC in a study that sustainable farming practices, including land-use change calculations, in the U.S. give soybean farmers a smaller carbon footprint than producers in major competing countries – including countries in the EU. When land use change – conversion of environmentally sensitive land into ag production - is included in the calculation, the carbon footprint of U.S. soybeans is far below soybeans produced in Brazil and Argentina and even comes in below European countries like France and Italy. “Cultivation is the major contributor to carbon footprint,” says USSEC about the analysis. “In general, the U.S. has higher yields, minimal fertilizer use, and efficient machinery, all of which help to minimize U.S. Soy’s carbon footprint. Land use change has a significant impact on carbon footprint. Deforestation in South American countries has had a negative impact on the carbon footprint of soy produced in that region. The United States is the number one country in the world for preservation of public forestry lands.” |

And last year, as Brazil took criticism from world leaders as massive fires burned in the Amazon, President Jair Bolsonaro lashed out on Twitter, saying, “We're fighting the wildfires with great success. Brazil is and will always be an international reference in sustainable development. The fake news campaign built against our sovereignty will not work. The US can always count on Brazil.”

The last sentence was aimed at President Donald Trump, who came to Bolonaro’s defense, saying he was “working very hard on the Amazon fires and in all respects doing a great job for the people of Brazil – Not easy.”

The incoming Biden administration might not be so understanding.

President-elect Joe Biden, during a September debate with Trump, suggested Brazil be punished economically if it doesn’t stop deforestation. He also suggested he might work with other countries to provide $20 billion to stop the destruction of the Amazon rain forest.

Bolsonaro reacted sharply. “My government is taking unprecedented actions to protect the Amazon,” said in a series of tweets. “What some have not yet understood is that Brazil has changed. Today, its President, unlike the left, no longer accepts bribes, criminal demarcations or unfounded threats. OUR SOVEREIGNTY IS NON-NEGOTIABLE.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.