One of the newest entrants in the quest for more sustainable agriculture is not very well known in farming circles, but that may be about to change.

After five years incubating and honing their ag and food research centered in X — The Moonshot Factory, the startup Mineral “graduated” this week to be an official member of Alphabet, the parent company of Google. X, formerly Google X, is located in Mountain View, California, where several engineers, scientists, and creatives gather each day to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems.

CEO Elliott Grant, who has a Ph.D. in engineering and worked in aerospace, the produce industry and nutrition to help consumers use artificial intelligence earlier in his career, said the firm’s focus is threefold: developing sensing technology that can generate rich data sets about plants; organizing agriculture data from disparate sources for machine learning and building powerful software algorithms; and conducting research that can meaningfully advance the fundamental understanding of plants. He sat down with Agri-Pulse last week to discuss the firm’s journey and future plans.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How was your work changed since you joined Mineral in 2017?

Back then, it was literally just a couple of engineers exploring a few ideas. But now, we’re seeing things come to reality that we could almost imagine five years ago. If you'd seen our early experiments, you'd have said this technology is never going to work because it’s slow and cumbersome with low accuracy. Today, we have machines that can go through a field, look at every plant, extract information and have it delivered to a user, such as a plant breeder, almost immediately,

Why does X or Alphabet care about agriculture?

X doesn't have a particular thesis. It doesn't say “we want to do agriculture.” In fact, if you look at the graduates that have come out of X, it was very early in bringing AI to solve problems of health care. Agriculture is one of the largest industries we have, give or take $4 trillion globally. According to McKinsey, agriculture is one of the least digitized industries in the world and yet one of the most important, existentially, for humanity. So, in many ways, it makes sense that Alphabet should be trying to bring its technology to the problems of agriculture. It's a big enough space and we had a team that was passionate about trying to tackle it.

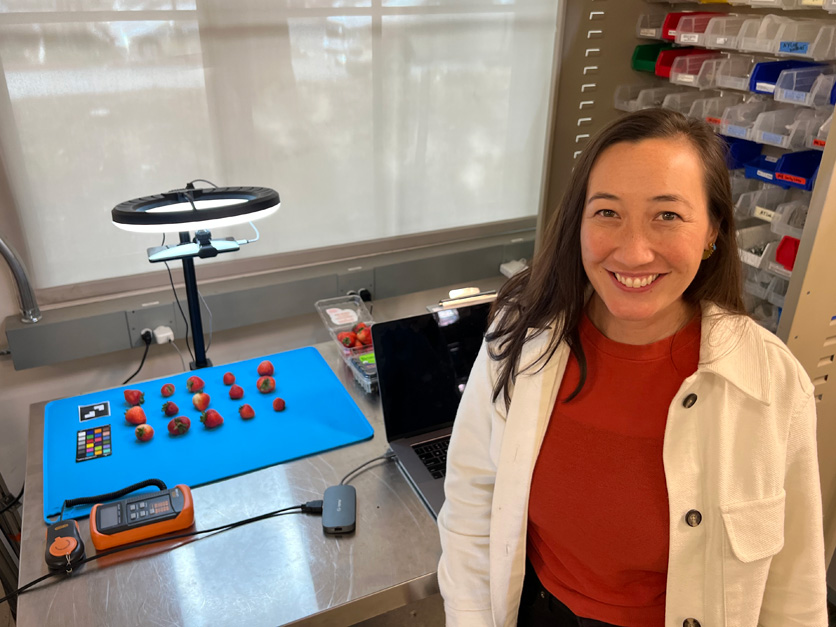

Mineral Chief Commercial Officer Erica Bliss showcases the firm's mobile scanning software that can be used to detect defects in strawberries and potentially, other crops sh showc

Mineral Chief Commercial Officer Erica Bliss showcases the firm's mobile scanning software that can be used to detect defects in strawberries and potentially, other crops sh showc

What types of crops are you focused on?

One of the challenges of traditional row crops like corn, beans and wheat is you have to wait a full year to do an experiment. And if operate in both the northern and southern hemispheres, maybe you can get two experiments a year. This affects anyone doing some sort of crop or input development. So in parallel to working on row crops, we intentionally work in strawberries, for example, because it's close by in California. It's a continuously growing crop from March to October. And it allowed us to iterate really quickly to multiple experiments that would have been impossible if we were just focused on row crops. So there was a lovely synergy between rapidly iterating in produce — which arguably isn’t going to have the acreage impact — but taking those lessons over to row crops where we knew we could have much more impact at scale.

And in fact, there was a third piece of the puzzle, which is making sure we pay attention to the underserved crops, the so-called orphan crops. Think cowpea and pigeon pea, cassava and millet — crops which are extraordinarily important in the global south for nutrition and are completely ignored, really from a commercial point of view because they are not commercially interesting. So very early on, we said we want to make sure we're placing effort and investment on all these different diverse types of crops.

During your early experiments, you worked with Syngenta, Driscoll’s and CGIAR, but who is your ultimate customer?

That’s a good question and it took us a while to figure out the right answer.

It’s worth explaining what we do and then get to our customer because those two things go hand in hand. What we're fundamentally doing is building foundational technology for the industry. It very much reflects our Google DNA, right? Can we build tools that are generally useful to lots of people, in lots of ways? And there are two fundamental tools we've been building: one is around plant perception and the other is the ability to analyze these huge amounts of data that are coming off farms.

This is a trend we see going forward as more and more data is going to become available. So, the first key point is we're building foundational tools and technologies and platforms that allow other people to build their applications and products on top of them. So that sort of tells you who we're working for because we are not selling directly to the farmer. We’re working with industry partners for a couple of really important reasons.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse by clicking on our link!

We are experts in deep learning and AI and robotics. We are not experts in soybean farming in Iowa or strawberry farming in California. So we intentionally partner with companies who have that domain expertise. And together we can create things that neither of us could build upon. So that informed our strategy to say “we're going to work with existing players in the industry who are leaning in on sustainability, adopters of innovation and have the wherewithal to take this technology and bring it to market.” We're not saying “we only want to work with one or two people.”

Early on we did because we were still experimenting, but now that we're graduating, our goal is to work with as many partners as possible. The diversity of agriculture means there will be hundreds or thousands of solutions to meet the individual needs of farmers. And there's no way that one company can do all of that.

Are you a threat to, or a collaborator with, the equipment companies that are also working to develop some of the same technologies?

The headline for me is I want more companies coming into agriculture. I'm not worried about the competition. As an industry, the more brains and talent coming into the space, the better.

What can we do to accelerate that motion? Strategically, we've asked how we can provide these foundational tools that help all those other players go faster. It’s effectively giving them the option to say, look, we're going to focus on perception and this computing power.

If you have an amazing robot, for example, that can pick strawberries or grapes or whatever … is it better for us to work together? Can we help you go faster? Again, think about Google's DNA. What is Google excellent at? It's providing these foundational platforms that enable you, that are helpful to you. That's pretty much the philosophy we've brought to this space.

I think we're at the beginning of Day Zero of ML (machine learning) in agriculture. So, we should be focused on how we all can go faster, rather than let’s all fight over what is currently a pretty small pie.

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com.