Shipping disruptions in the Red Sea due to attacks from Houthi rebels and the ongoing, drought-induced slowdown of goods through the Panama Canal are driving up freight costs and putting a focus on the vulnerabilities of key chokepoints in agricultural shipping lanes.

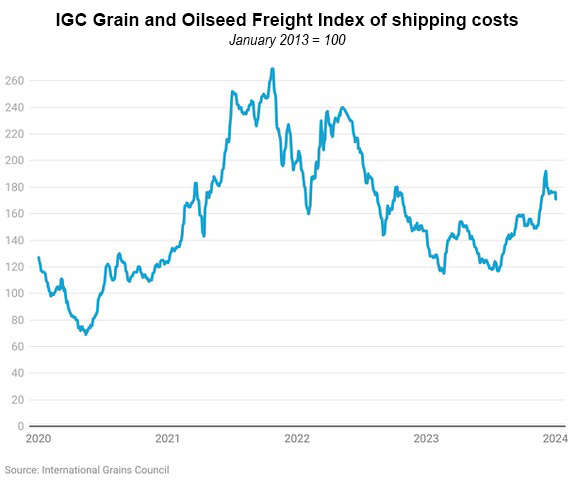

Freight costs haven’t reached the levels seen during the worst of the pandemic-related supply chain snarls in 2021 and 2022, but the disruptions have forced the diversion of shipping to longer, slower routes or through alternate ports.

Ships that normally use the Red Sea are being forced instead to go around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, for example, and exports of some U.S. ag commodities are being switched to Pacific Northwest ports in lieu of using the Panama Canal.

The International Grains Council’s index of global shipping costs for grains and oilseeds rose more than 50 points from the middle of 2023 to a reading of 171 on Jan. 2. That compares to highs of 269 in October 2021 and 240 in May 2022.

“These issues have not only underscored the fragility of key maritime routes but also have had a cascading effect on global agricultural supply chains, having the potential to disrupt 2024 U.S. agricultural exports severely,” economists from North Dakota State University and the University of Connecticut write in an analysis of the situation. “The potential implications for exporters of major crops like corn and soybeans are considerable, encompassing increased transportation costs, potential delivery delays, and a broader reassessment of trade strategies.”

Waiting times for ships to move through the Panama Canal once averaged about five days; as of this month, the analysis says that has escalated to more than three weeks.

The Red Sea isn’t fully blocked — some Chinese ships aren’t being affected — but the disruption has raised insurance costs and has significantly increased shipping times for grains moving out of Europe and the Black Sea, said Joe Glauber, a senior fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute and a former chief economist for USDA.

“How long it lasts is anyone’s guess at this point,” Glauber tells Agri-Pulse. “It largely means higher costs, and … for the exporting countries that are most affected that means lower prices for their producers. They’re competing in global markets.”

He said higher prices could also hit consumers in regions such as East Africa that depend on grain that normally transits the Suez Canal, although global grain prices have come down from the highs they reached when Russia invaded Ukraine and disrupted its exports in 2022.

According to the World Trade Organization, grain and oilseed shipments through the Suez Canal fell from 7.2 million metric tons in November to 5.9 million in December, and then plummeted to 900,000 tons during the first half of January, 63% below the three-year average amount for that period.

Wheat shipments “plunged in the first half of January,” falling 40% below the amount that moved through the Red Sea during the same period in January 2023, the WTO says.

Alternative shipping routes can be dramatically longer. Odesa, Ukraine, is 4,117 miles from Kenya via the Suez Canal but 9,724 miles away if the ship has to go around the Cape of Good Hope, according to an IFPRI analysis. A ship carrying grain from Thunder Bay, Ontario, to Kenya would have to travel 10,677 miles around the Cape of Good Hope, compared to 5,134 miles through the Suez Canal.

In December, 8% of the wheat bound from Europe, Russia and Ukraine to East Africa and Asia that normally transits the Suez Canal was shipped via alternative routes; that figure jumped to 42% by the first half of January, according to the WTO.

U.S. wheat shipments have yet to be significantly affected by the Red Sea disruption.

“We have not heard of any specific up or down effect on U.S. wheat demand from the Red Sea closure,” said Steve Mercer, a spokesman for U.S. Wheat Associates, the wheat industry’s export development arm. He said the impact on shipping costs for wheat “would be hard to quantify right now.”

The Red Sea disruption has raised concerns within the U.S. government. The Federal Maritime Commission has scheduled a public hearing Feb. 7 on the issue and has authorized several shipping lines to implement emergency surcharges or general rate increases more quickly than they usually could.

It’s easy to be “in the know” about what’s happening in Washington, D.C. Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! Simply click here.

The commission’s announcement says next week’s hearing will enable “stakeholders in the supply chain to communicate with the commission how operations have been disrupted by attacks on commercial shipping emanating from Yemen, steps taken in response to these events, and the resulting effects.”

According to a report by Statista, 22% to 23% of all goods that are shipped by sea between non-neighboring countries, including ag commodities as well as fertilizer, oil and other products, move through the Red Sea.

The Panama Canal’s share is smaller, but it normally handles about 3% of world trade and is critical for shipping soybeans and other commodities from Gulf of Mexico ports to China and other Asian markets. More than 26% of U.S. soybean exports and 17% of corn exports were shipped through the canal in fiscal 2022.

To address the shortage of water in the canal, the Panama Canal Authority has reduced daily transits from the usual 36 to 40 to just 24. The reduced number of slots is being dominated by container ships, automobile carriers and cruise ships that can book their transit much earlier than agricultural exporters can, said Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soy Transportation Council.

The authority also is reserving a limited number of slots based on the size of the customer, he said.

Mike Steenhoek, Soy Transportation Coalition“While agricultural exporters are certainly important to the Panama Canal, they do not compare with the large steamship lines that transport containers or other freight through the canal. These types of vessels also pay higher tolls to transit the canal. A container vessel can easily pay $500,000-$800,000 per transit. A dry bulk vessel, in comparison, will pay around $200,000,” he said in an email.

Mike Steenhoek, Soy Transportation Coalition“While agricultural exporters are certainly important to the Panama Canal, they do not compare with the large steamship lines that transport containers or other freight through the canal. These types of vessels also pay higher tolls to transit the canal. A container vessel can easily pay $500,000-$800,000 per transit. A dry bulk vessel, in comparison, will pay around $200,000,” he said in an email.

“There is nothing sinister or malicious behind the Panama Canal Authority’s response to the drought conditions. They have to apportion the limited number of slots some way,” Steenhoek added. “It is just resulting in agricultural exports having to explore other options.”

The NDSU-Connecticut analysis says the operational changes for the canal also have led ships to lighten loads to meet draft reductions.

“Vessels unable to secure a booking or those missing their bookings due to previous delays may now face waiting times of up to two to three weeks for a new slot at the canal. Moreover, the increased waiting time for transit has led to tighter vessel capacity, which is expected to raise spot rates even further,” the analysis says.

The analysis warns that low water levels will continue to be a problem for the canal, “due to strengthening El Niño conditions and predicted droughts in Central America for the remainder of 2024.”

Ironically, last fall some shipments were diverted from the Panama Canal to the Suez because of the water shortage, said Steenhoek. “With the attacks in the Red Sea, that has resulted in a further shift away from the Suez Canal to the Cape of Good Hope route,” he said.

Some exporters have started shipping by rail to the Pacific Northwest “in order to avoid the Panama Canal, Suez Canal, and the Cape of Good Hope,” he said.

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.