WASHINGTON, April 16, 2014 - Federal, state and local wildlife specialists are gathering in Montgomery, Alabama, this week to develop a coordinated strategy for dealing with what USDA calls one of the country’s “most destructive and formidable invasive species -- feral swine, or wild pigs.

The department’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) says there are now about 5 million of the animals in the U.S., rooting and wallowing their destructive paths through at least 39 states and causing farmers and ranchers an estimated $1.5 billion a year in damages and control costs. The pigs are destroying native habitat and crops, eating endangered species and spreading disease.

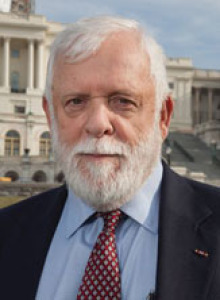

“Feral swine don’t know boundaries and what happens in one state affects neighboring states,” said Dale Nolte, APHIS’ new national feral swine initiative coordinator. “Only through a concerted, comprehensive effort with the public and our state and federal partners can we begin to turn the tide on feral swine expansion and reduce their negative impacts on our economy and environment.”

Congress this year appropriated $20 million to deal with the problem, which will be highlighted at the gathering in Alabama, the 2014 International Wild Pig Conference. APHIS aims to have its program operating within 6 months, with about half of the funds going toward state projects. The rest will be used to set up procedures for disease monitoring, including the development of new surveillance and vaccination methods, research and administration. Funding levels for state projects will be based on current feral swine population estimates.

“Feral swine are one of the most destructive invaders a state can have,” said Edward Avalos, USDA’s undersecretary for marketing and regulatory programs. “It’s critical that we act now to begin appropriate management of this costly problem.”

The wild pigs, also known as razorback hogs, carry diseases that can affect people, livestock and wildlife, as well as water supplies. They also cause widespread damage to crops ranging from Midwestern corn and soybeans to sugar cane, peanuts, spinach and pumpkins. Sometimes called “nature’s rototillers,” their characteristic rooting and wallowing damages natural resources, including habitat used by waterfowl, as well as archeological and recreational lands. They also compete for food with native wildlife, such as deer, and consume the eggs of ground-nesting birds and endangered species, such as sea turtles.

Avalos said surveillance and disease monitoring are key parts of the initiative because the animals can carry and transmit up to 30 diseases and 37 different parasites to other livestock, including the swine population raised for food. Feral swine will be tested for diseases of concern to pork producers such as classical swine fever, which has not been found in the U.S., as well as brucellosis, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, swine influenza and pseudorabies.

”Ensuring that domestic swine are not threatened by disease from feral swine helps ensure that U.S. export markets remain open,” APHIS said in a news release. Those markets were valued at $6.3 billion in 2012, according to the National Pork Producers Council.

Thirty years ago the animals were found in just 17 states, mostly in the southern U.S. Since then their range and population has exploded. APHIS attributes the rapid spread to natural range expansion, illegal trapping and movement by people, and escapes from domestic swine operations and hunting preserves.

Nolte said USDA’s Wildlife Service and equivalent state agencies will take the lead in eradicating the problem.

“We’ll use any feasible, reasonable method to get rid of these animals,” Nolte said in an interview, adding that “lethal removal is the primary technique.” Sometimes, he said, Wildlife Service agents will gradually build a large baited cage, allowing the pigs to get used to the surroundings. Then, when monitors show an entire clan of pigs – up to 20 animals known as a “sounder” – is in the cage, the trap is shut and the sounder can be euthanized.

Often sharpshooters are employed, sometimes firing from helicopters, Nolte said, and Auburn University researchers are developing a “reproductive inhibitor,” or contraceptive measure.

Nolte said the initiative at first will concentrate on eradicating the pigs in “fringe” states such as Maine where the problem is relatively small, while trying to control the damage in other states, such as Texas, which is home to almost half of the nation’s wild pig population.

“Our goal is to eliminate the problem in maybe two states every three to five years,” Nolte said, acknowledging that the job won’t be easy. “These animals are hardy, adoptive, opportunistic and omnivorous,” Nolte said. Plus they breed well, with a sow capable of producing two litters of eight to 14 piglets a year. And the survival rate?

“They have a saying in Texas,” Nolte joked. “There were eight pigs in the litter and 12 survived.”

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.