WASHINGTON, Mar. 8, 2017 - Do sugar and other sweeteners in the diet cause obesity?

There is no direct evidence for that, say sweetener producers and food and beverage makers, who are getting hammered heavily with nutritional regulations and dietary policy linking sweeteners to increased incidence of child and adult obesity.

The World Health Organization, for example, has adopted a recommendation of a 10 percent added sugars maximum in its campaign against both adult and child obesity, and it recommends a ceiling of 5 percent as even more healthful.

Jack Roney

The public fight against sugar includes the recently updated U.S. Dietary Guidelines, which includes for the first time a specific ceiling for added sugars, at 10 percent of daily calories, compared with an American consumer average near 15 percent now. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration’s new food label format, effective in mid-2018, requires “added sugars” to be listed separately from total sugar content in volume and as a percent of recommended daily diet. The FDA says the point of the upper sweetener limit is that’s it is “difficult to meet nutrient needs while staying within calorie limits if you consume more than 10 percent of your total daily calories from added sugar.”

Courtney Gaine

But Courtney Gaine, a dietitian and president of the Sugar Association, addressed the issue at a sweeteners industry gathering in California last week. Gaine noted that while those guidelines address caloric sweeteners as a proportion of a healthful diet, “there is no mention of obesity in the 10 percent” recommended maximum for added sugars, she said, and the scientific reviews that led to the guidelines and label requirements included no evidence for such a linkage.

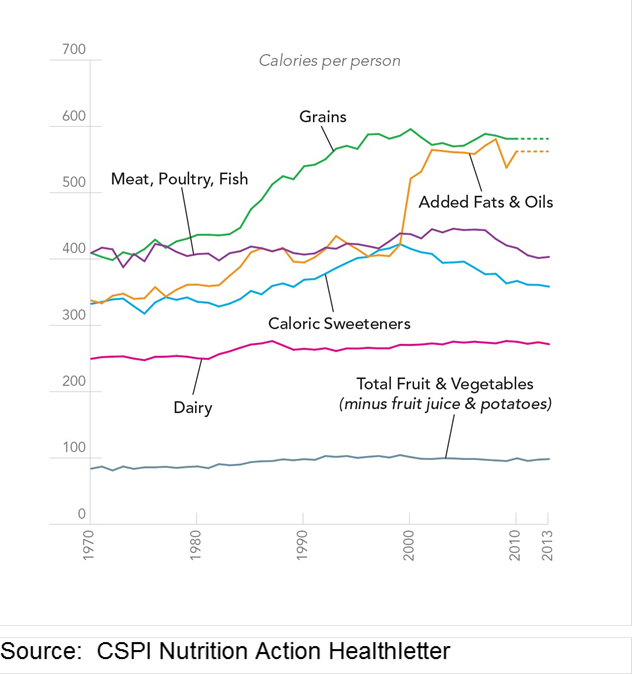

At the same event, Jack Roney, director of economics and policy analysis for the American Sugar Alliance, said that associating sugar consumption with obesity “just doesn’t make sense” when the trend in Americans’ consumption of sugar and other sweeteners is compared chronologically with the rapid increase in obesity across the past 40 years. He pointed out that per capita sugar consumption has fallen substantially since 1974 while the national incidence of both adult and child obesity has climbed more than 300 percent.

The marked rise in obesity “is a serious event,” Roney said, but sugar should not be singled out as the leading culprit. While Americans increased their daily diets by 374 calories from 1974 to 2014, including 225 more calories in fats and oils, their total sweeteners crept up by just 33 calories, he said, so it isn’t logical to pin all the blame on sweeteners.

Indeed, U.S. dietary experts agree with the sugar industry that total calorie consumption is perhaps the main American dietary problem. Bonnie Liebman, director of nutrition for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, agrees that “it was not just added sugars that fueled the obesity epidemic,” and that the increased consumption of grains (especially white flour), fats and oils contribute as well.

Liebman notes that it is not surprising that, as Roney argues, obesity continued to surge after higher sweetener consumption declined

Liebman notes that it is not surprising that, as Roney argues, obesity continued to surge after higher sweetener consumption declined

Most people who become overweight or obese, she said, do not return to a healthy weight and keep the weight off long term, so the incidence of obesity continues to rise. Plus, she said, when one looks back to around 1990 or before, “The initial surge in overweight and obesity did occur at about the same time as the jump in intake of added sugars.”

Furthermore, Liebman said, though total calorie intake may be the biggest problem, “That doesn’t leave added sugars off the hook. The impact of sugary drinks on weight gain is unique, and it is a major factor in the obesity epidemic. That, to me, is separate from added sugars as a whole.”

Reducing sugary drinks has become the focus, in fact, of many who advocate healthy nutrition. The American Diabetes Association, for example, stresses the importance of reducing total calorie intake more than reduction in just sugars, but also emphasizes that “drinking sugary drinks is linked to type 2 diabetes . . . and recommends that people limit their intake of sugar sweetened beverages.”

Several American cities – including Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Boulder, Colorado – have taken sides in the debate, enacting soda taxes in the hopes of making their citizens healthier, and as a way to raise revenue. In Philadelphia, for example, the City Council has approved a 1.5 cents per ounce tax. As expected, beverage sales have fallen, but supermarkets and beverage distributors say they are planning layoffs or have already made cuts.

#30