If history is a guide, there’s little chance Congress will enact a new farm bill this year. Congress hasn’t enacted a farm bill in the same year it was first introduced since 1990, which is what lawmakers are trying to do this year.

Every bill since 1990 has taken two to three years for lawmakers to finalize.

But there are at least two reasons why a farm bill could still become law this year. One reason is politics. Republicans are increasingly citing the uncertainty created by President Donald Trump’s trade policy as a reason they need to enact a new farm bill.

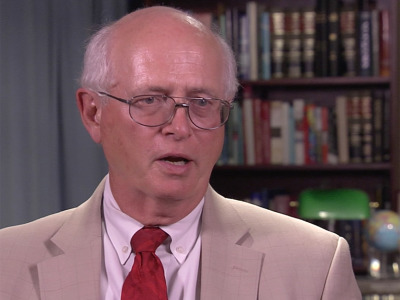

“Agriculture is such an export-driven industry in the United States, we have to be able to keep our head above the water line” until Trump’s trade policy starts showing results, said Rep. Frank Lucas, who chaired the House Agriculture Committee during development of the 2014 farm bill. “That just adds more emphasis to passing a farm bill.”

Rep. Frank Lucas, R-Okla.

Some lawmakers also have a sense of urgency, knowing that passing a farm bill likely won’t be any easier next year after the mid-term elections. Republicans are likely to have a smaller House majority, or Democrats could be in control by a small margin. That’s the message Lucas says he’s been delivering to colleagues: “We can be reasonable, rational and we can accomplish great things. Or we can roll the dice politically and see what happens.”

Another reason some think a new bill could still be enacted this year is that the differences between the House and Senate bills – except on nutrition assistance – don’t involve deep ideological or partisan differences as has sometimes been the case.

The bill that the Senate Agriculture Committee approved June 13 largely preserves the structure of the 2014 farm bill and continues funding most existing programs.

The Senate is expected to debate the committee’s bill next week. The House defeated its farm bill May 18 but could reconsider it as soon as this week if Republican leaders hold votes on a pair of immigration bills. Some conservatives voted against the farm bill because they said they wanted the House to act first on immigration policy.

House and Senate approval of the bills would allow negotiations to begin on a final version, a process that normally has taken several months to complete.

But Bob Young, a former chief economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation who served as chief economist for the Senate Agriculture Committee from 1987 to 1991, said he thinks a House-Senate conference committee could reconcile differences between the two bills in a few weeks, if House and Senate leaders could agree on what to do about the nutrition title.

The nutrition title remains the biggest single sticking point, by far, because of the House bill’s expanded work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Bob Young

“Nutrition could blow this whole thing wide open,” said Young, who now serves as the president of Agricultural Prospects. The rest of the final bill would be easy enough to negotiate that it “could be ready by the August recess,” Young said.

Lucas said that House Speaker Paul Ryan, who has been personally involved in the effort to expand SNAP work requirements, “at this moment is still very, very committed to his second big bold reform effort after tax reform.”

Lucas said that many of the other differences between the two bills should be relatively easy to resolve, and don’t require agreements between House and Senate leaders.

One of the bigger differences between the bills is on the Conservation Reserve Program. The House bill would increase the acreage cap from 24 million acres to 29 million. The Senate bill would raise it to 25 million. Negotiators will have to find an agreement between the two. Disagreements such as those “can all be sorted out,” Lucas said.

Except for payment limit provisions, the commodity titles in the two bills are very similar: Senate Agriculture Chairman Pat Roberts, R-Kan., resisted pressure from Midwesterners to shift spending from the Price Loss Coverage program to Agriculture Risk Coverage.

But another veteran of farm policy debate, Ferd Hoefner, believes that conferencing the two bills will still be difficult.

“We certainly have never gone into a conference before with a highly partisan bill on the one side and a highly bipartisan bill on the other side, so these are uncharted waters, and those waters could be made even rougher should the president decides he cares about something in the bill,” said Hoefner, senior strategic adviser for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

“In the final analysis, a conference report that gets 60 votes in the Senate will need to look very much like the bill the Senate will approve next week," he added, "so it will come down to whether or not House Republican leadership is willing to go there or not.”

Lawmakers are quickly running out of time to finish the bill. The House, and possibly the Senate, will be in recess during August, and lawmakers will be eager to be out of Washington as much as possible in September and October to campaign.

The 2014 farm bill expires Sept. 30. No farm bill has passed before the expiration of the previous bill since 1977, and no farm bill has been enacted after an election, during a lame-duck Congress, since 1990.

The hard deadline for Congress to act is Dec. 31, when the Margin Protection Program for dairy expires. That would trigger implementation of provisions of the 1949 farm law, which could force USDA to raise milk prices. When Congress was unable to agree on a bill after the 2012 election, lawmakers passed a one-year extension of the expired 2008 law.

Here is a look at some key differences between the House and Senate bills:

COMMODITY PROGRAMS

House bill: Adds trigger for Price Loss Coverage to increase reference prices. Increases coverage levels under dairy’s Margin Protection Program (MPP) to $9 per hundredweight.

Eases payment limits for pass-through entities and allows nephews, nieces and cousins to qualify for payments as part of family farming operation.

Senate bill: No changes to PLC. Increases substitute yield for calculating revenue guarantee under Agriculture Risk Coverage. Changes to MPP are similar to the House bill.

Tightens the means test for commodity payments to $700,000 in adjusted gross income, down from $900,000.

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

House bill: Raises limit on Conservation Reserve Program from 24 million acres to 29 million acres. Kills the Conservation Stewardship Program and uses the savings to boost the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and fund other priorities inside and outside the conservation title.

Removes livestock funding set-aside for EQIP. Increases EQIP funding from $1.75 billion in fiscal 2018 to $2 billion in FY19 and $3 billion by FY23.

Cuts $800 million from the conservation title in order to fund other priorities.

Senate bill: Increases CRP to 25 million acres. Cuts CSP enrollment cap from 10 million acres a year to 8.8 million annually.

Reduces EQIP livestock set-aside from 60 percent to 50 percent. Funds EQIP at $1.47 billion in FY18 and $1.6 billion in FY23,

CROP INSURANCE

House bill: Both bills make minor relatively minor changes. The House bill bars producers with revenue policies from also having ARC individual-level coverage. Eliminates funding for education, which is used in the Northeast.

Senate bill: Authorizes incentives for adopting conservation practices, including cover crops. Makes hemp eligible for insurance. Provides new incentives to insurance agents to sell whole-farm policies.

ENERGY

House bill: Eliminates the energy title, strips Rural Energy for America Program of mandatory funding.

Senate bill: Retains energy title and mandates funding at existing levels by cutting subsidies for domestic cotton textile mills.

NUTRITION

House bill: Expands work requirements to adult SNAP recipients in their 50s and to parents of children above the age of 6.

Eliminates broad-based categorical eligibility, essentially making people ineligible for SNAP if their income is 30 percent over the federal poverty rate, or $26,000 for a family of three. Some states make people ineligible up to twice the federal poverty level. Requires recipients to be current on child support.

Requires SNAP recipients, if they are not elderly or disabled, to document their utility expenses for purposes of calculating benefits.

Senate bill: Doesn’t touch work requirements or broad-based categorical eligibility or change utility requirements for benefit calculations.

RESEARCH

House bill: Provides no new funding for the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research.

Senate Bill. Provides $200 million in new funding for FFAR.

ANIMAL VACCINES

House bill: Provides $150 million in one-time funding for a foot-and-mouth disease vaccine bank. The industry wanted $150 million in annual funding.

Senate bill: Authorizes creation of a vaccine bank but doesn't mandate funding for it.

USDA REORGANIZATION

House bill: Authorizes merger of Farm Service Agency, Risk Management Agency and Natural Resources Conservation Service into farm production and conservation (FPAC) mission area.

Senate bill: Also authorizes FPAC. Requires USDA to have undersecretary for rural development.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com