Modesto is at the heart of peach country for the nation. Yet children sitting down for lunch in the Central Valley city’s public schools are likely being served cheaper peach products imported from countries where production costs are low and regulatory oversight is weaker.

This is despite a number of recent actions on the state and federal level to close loopholes and better enforce the Buy American provision of the federal Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act of 1998.

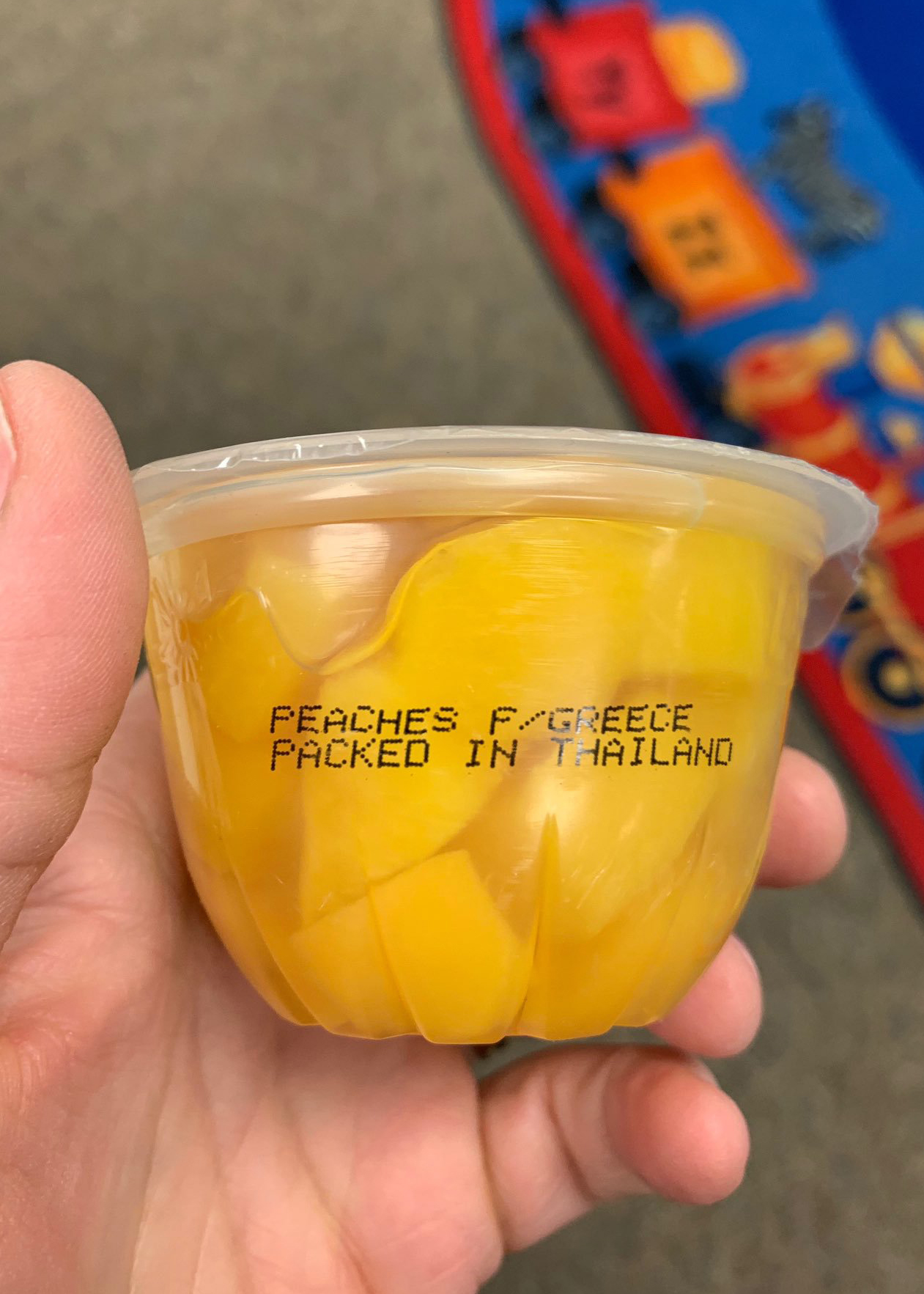

In early November, Rich Hudgins, who is president of the California Canning Peach Association, was sent a photo from a Modesto school lunch of a Dole brand peaches packaged in Thailand and grown in Greece, one of the California industry’s closest competitors alongside China.

“Of all the cities that you would expect this to occur in, Modesto would be the last,” he said in an interview. “I suspect the procurement folks thought since it was a U.S. company and brand, and California is a big peach producing state, then of course it’s domestic.”

Del Monte Foods employs 1,500 workers in its Modesto plant and Seneca Foods employed about 300 in the city before closing its plant in 2018.

While one incident of imported peaches may seem like a minor event, to Hudgins it’s the latest front in a four-year policy battle. Finding foreign peaches in school lunches, Hudgins had spearheaded an effort in 2015 that led Sacramento City Unified Schools to immediately retreat from its contracts for imported Chinese fruit. This helped Hudgins draw state legislators into the discussion.

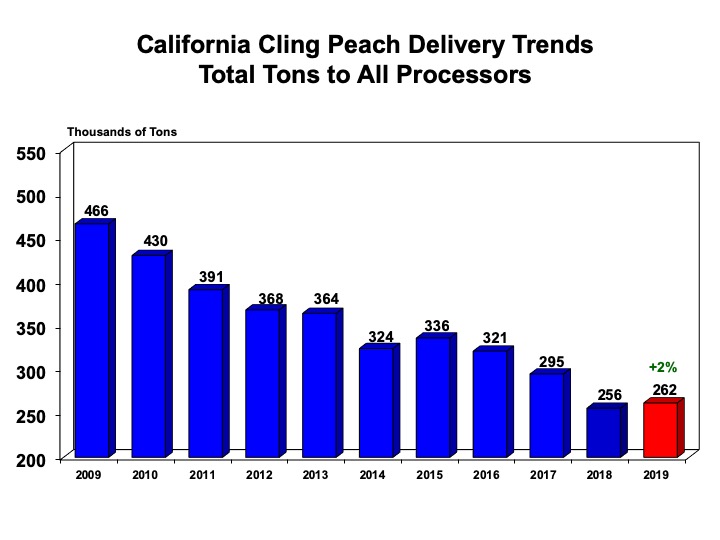

(source: California Canning Peach Association)

In 2016, Senator Cathleen Galgiani, D-Stockton, requested a Department of Education audit to determine which schools were in compliance with the Buy American provision. The audit found none of the school districts reviewed had adequate policies for meeting the requirements. They had also purchased foreign-sourced foods and did not have any documentation to justify the purchases. The audit notes that California receives nearly $2 billion a year through the federal breakfast and lunch programs.

This spurred Senator Richard Pan, D-Sacramento, to propose Senate Bill 730, requiring the department to monitor and support schools in complying with the Buy American provision. California passed the bill in 2017, as Congress was also taking up the initiative. Part of the argument then was that “spending taxpayer dollars to import products from nations not complying with equivalent emissions standards” violated the state’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Democratic Rep. John Garamendi had introduced the American Food for American Schools Act with Republican Rep. Doug LaMalfa. The bill would have required school lunch providers to apply for a waiver when purchasing foreign products, but it failed to pass. The congressmen reintroduced the bill in February 2019, adding a provision that parents would be notified when students are served “foreign-produced foods paid for by taxpayers.”

Hudgins found food industry partners across the country facing the same issue. Labor unions, fearing workers were losing jobs due to unfair competition, joined the fight.

“We learned that over half the states in the country had schools that had gotten bids from distributors that resulted in imported products being served in the school feeding program,” he said.

A peach cup found in a Modesto area elementary school contains peaches grown by one of California's greatest competitors.

More than 80% of the apple juice served in schools was of Chinese origin, they discovered. Yet it was fish sticks that levied the most substantial policy change. The coalition, now incorporating dozens of trade groups, found up to 70% of the sticks served in schools came from fish caught on Russian vessels and processed in China. They also found grass-fed beef coming in from Brazil. Dozens of trade groups lobbied Congress.

The problem stems from two exemptions included in the Buy American provision. The National School Lunch Act was signed in 1946 and had clear language to supply children with food that was 100% domestically grown, which supported farmers returning to work after the war. The Buy American provision of 1988 then delivered implementation guidance on the act to USDA. Now foods, like bananas, not produced domestically, would be excluded from the regulation. A second exclusion applied to any products with a significant price differential, which Hudgins said was likely to prevent suppliers from gouging the taxpayer.

“As a practical matter today, it gives the opportunity for any school interested in buying solely on price to purchase the cheaper foreign product,” he said.

While the exclusions still exist, the coalition was able to insert new requirements into the 2018 Farm Bill. Section 4207 directed USDA to enforce full compliance with the act within 180 days and added that fish must be harvested within the U.S. or by a U.S. ship, a win for the Alaskan halibut industry. In June, USDA reported to Congress it had clarified its standards on the exemptions and expanded its outreach and training for school food providers, while later issuing additional guidance to providers.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Modesto City Schools told Agri-Pulse a USDA audit completed in May found no violations of the Buy American provision within its schools. The district’s bidding process requires companies to submit Buy American certification statements, she said. Yet the peach cup was found by a parent in a school within the Sylvan School District, within a neighborhood in northern Modesto. The district was unable to comment in time for publication.

Hudgins said the photo is another indication how this remains a work in progress. The Farm Bill requirements do not provide a solution to fixing the problem. Reauthorization of child nutrition programs is still on the horizon, He continues to meet with congressional lawmakers in hopes of inserting language into the program.

“We're continuing to try to go back to the original congressional intent,” he said. “Let’s recognize the competitive landscape in 2019 is a lot different than it was in 1988.”

The trend today has not been good for the peach industry. About 30% of the nation’s supply is sourced from abroad. Meanwhile, canneries have not renewed contracts with about 30 growers following the 2019 season. Many have already been transitioning from labor-intensive stone fruits to more mechanized commodities like tree nuts. This season, California growers delivered about 260,000 tons of cling peaches to processors, down from 460,000 a decade ago. Foreign imports are up 10% this year. Hudgins sees the Buy American provision as one opportunity to slow the tide.

“In today’s environment, with an administration that is heavily focused on buying American,....if we can’t get it now, we’ll never get it," he added.

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com