Healthy margins for packers in recent years – and frustration at the amount of that profit making its way to producers – amplified calls for a less concentrated packing sector. Many in the meat industry have long criticized the ownership structure – four packers own the majority of the nation’s beef (85%), pork (70%) and poultry (54%) processing capacity – but facility shutdowns due to COVID-19 outbreaks also raised questions about the industry’s resilience due to its heavy reliance on a smaller amount of larger facilities.

In response, the Biden administration on Monday announced a $1 billion investment in processing capacity expansion and workforce resilience. But questions remain about which facilities will receive funding and what their bottom lines will look like after riding a few waves of the up-and-down cattle cycle.

“I recognize the need for balance, I recognize the need for us to be thoughtful about where these facilities are located and ensuring that their location and the decision is one that makes sense from an economic standpoint,” Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack said in an interview with Agri-Pulse.

Ag Secretary Tom VilsackThe money will be available through separate funds that will offer grants, loans, and loan guarantees. That distribution scheme, Vilsack said, will allow for everything from mom-and-pop butcher shops to mid-sized packing plants to be on the business end of funds. But that doesn’t mean the new facilities will have an easy path to stay in business, according to industry experts.

Ag Secretary Tom VilsackThe money will be available through separate funds that will offer grants, loans, and loan guarantees. That distribution scheme, Vilsack said, will allow for everything from mom-and-pop butcher shops to mid-sized packing plants to be on the business end of funds. But that doesn’t mean the new facilities will have an easy path to stay in business, according to industry experts.“I don’t think you can just open a new plant, say ‘we’re open for business,’ and say ‘we’re going to do well.’” Glynn Tonsor, an ag economist at Kansas State University, said in an interview withAgri-Pulse. “I’m not sure it would work well at any point in time, but it’s certainly not going to work well going into a few years when the number of cattle available is shrinking and the capacity to harvest them is growing.”

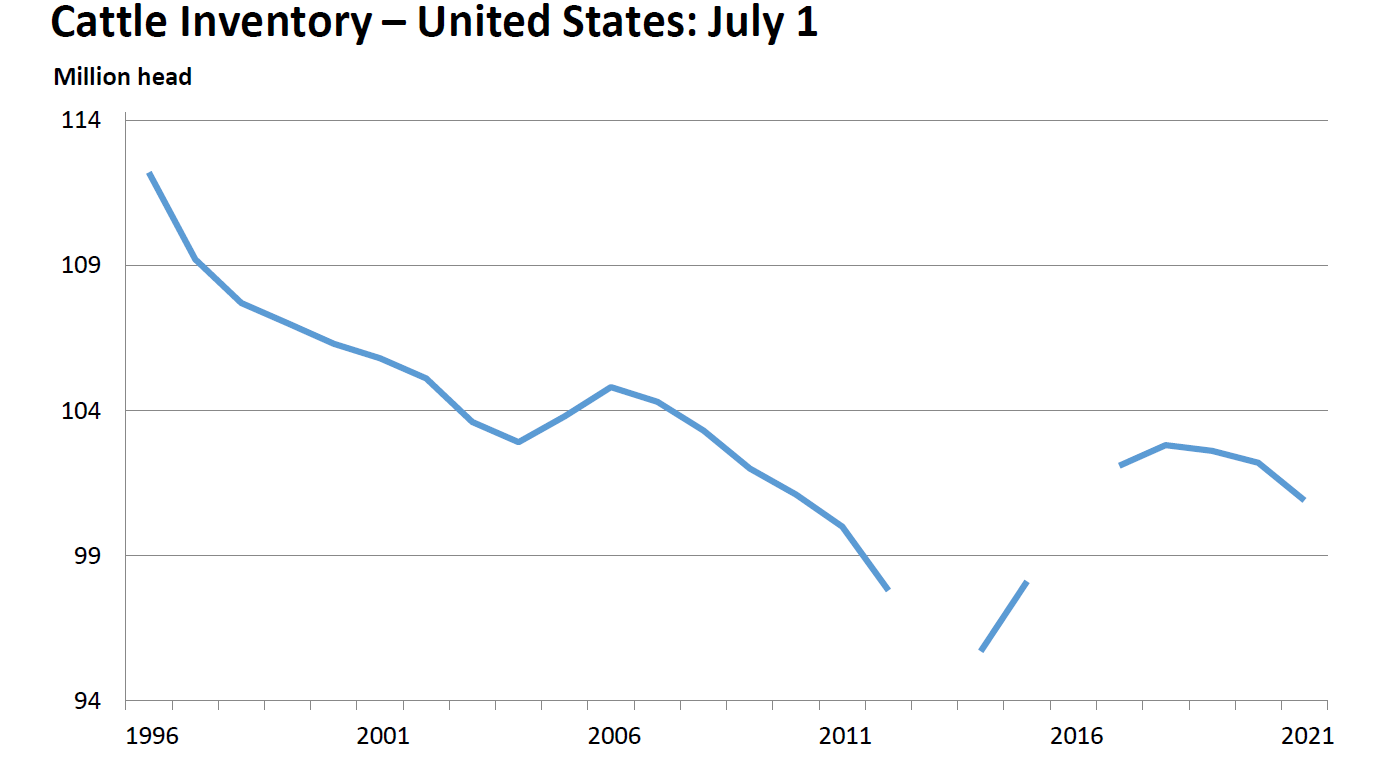

USDA is set to release a biannual report at the end of the month detailing the nation’s cattle inventory, but the latest figures in July began to show an expected decline in the cattle herd. Then, USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service reported a 1% drop in the cattle herd from July 2020 figures and said it expected the 2021 calf crop to be “down slightly” from the year prior.

What’s more, that July report came out as producers in many key cattle states were battling a summer drought that would later force some producers to sell animals due to weather concerns and feed availability rather than age or marketability.

“I think some of that would have happened even without the drought because of where we are in the cattle cycle,” Tonsor noted. “We were sort of set up for the herd to peak right before the pandemic anyhow. Pandemic disruptions … coupled with the drought … have quite magnified that.”

Many economists expect the looming market conditions – a tighter supply of cattle with a booming supply of processing capacity – to lead to better prices for live cattle. But those market conditions could also prove difficult for a facility looking to get its economic legs under itself in an already competitive marketplace.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription by clicking here.

Vilsack said he expects many of the supported facilities to be farmer-owned cooperatives who will want to spend their own money wisely. The department also plans to be mindful of geography and other factors that could either buoy or burden a new business.

And frankly, he said, some facilities are going to need more help than USDA will be able to provide.

“When you look at the amount of money, it’s pretty significant. But when you start looking at the cost of these facilities, the resource that we’re providing will itself be a limiting factor,” Vilsack said.

The precise cost of building a new facility will vary due to a whole host of factors, but a generally accepted rule of thumb in the industry is that each head of daily processing capacity will cost about $100,000. By that math, the White House's planned $375 million capital infusion by itself could add about 3,750 in daily processing capacity; some of the largest facilities currently in operation can accommodate about 6,000 head of cattle per day.

Source: USDA NASS (Note: July Cattle report suspended in 2013 and 2016 due to sequestration)

Source: USDA NASS (Note: July Cattle report suspended in 2013 and 2016 due to sequestration)The Biden administration has been consistent in saying a recent spike in food prices was the fault of the heavily consolidated meat market, something a more diversified production system would fix. But Jayson Lusk, head of Purdue’s ag economics department, is a little skeptical of that argument.

“It’s hard to explain a change with a constant,” he said. “Back up to 2014 and 2015 … we had really high retail beef prices then, we had really high cattle prices then, with basically the same ownership structure and concentration. Were the packers just being benevolent then? No, we were at a different point in the cattle cycle.”

For his part, Vilsack pointed to producers' steadily declining share of the food dollar and “significant growth in what the processing side of the equation is getting … that’s not inflation.”

USDA expects to dole out $150 million in grants to an estimated 15 projects this spring and another $225 million this summer. There’s also a $275 million loan program that will take applications by the summer and a previously announced $100 million loan guarantee effort. The funding, along with a separate $100 million investment in workforce concerns, is expected to involve several USDA mission areas, with Rural Development playing a leading role.

The timing of the announcements may make for some difficult early days for many of the facilities, but both Lusk and Tonsor offered a similar suggestion: Find a niche rather than pick a fight with the established powers. Having a story to tell – either about the quality of the product or the personal connection to the producer – could offer an edge, they said.

“If you’re a small- or medium-sized packer, it’s going to be hard to compete just in terms of minimum cost,” Lusk said. “I don’t think you can go out and produce generic beef and expect to be competitive.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.