Many farmers in the southern Plains and the West worry they can't produce good crops this year because of an abnormally dry winter and little prospect for moisture in coming weeks.

Texas grain farmer Scott Irlbeck is hoping to harvest 500 acres of non-irrigated winter wheat in June and is preparing to plant 500 acres of sorghum next month. But he fears he'll lose both crops, along with more than $38,000 worth of fertilizer, if rain doesn't come soon.

“I've got a lot of expenses already, between chemical fertilizer and seeds, and I haven't even planted anything yet,” Irlbeck said. “So with the weather, the drought situation — it's a scary time.”

The confluence of dry weather and high input prices is pushing farmers like Irlbeck to wonder whether it’s worth it to sink extra money into buying fertilizer and chemicals for crops that they worry won't make it through the summer.

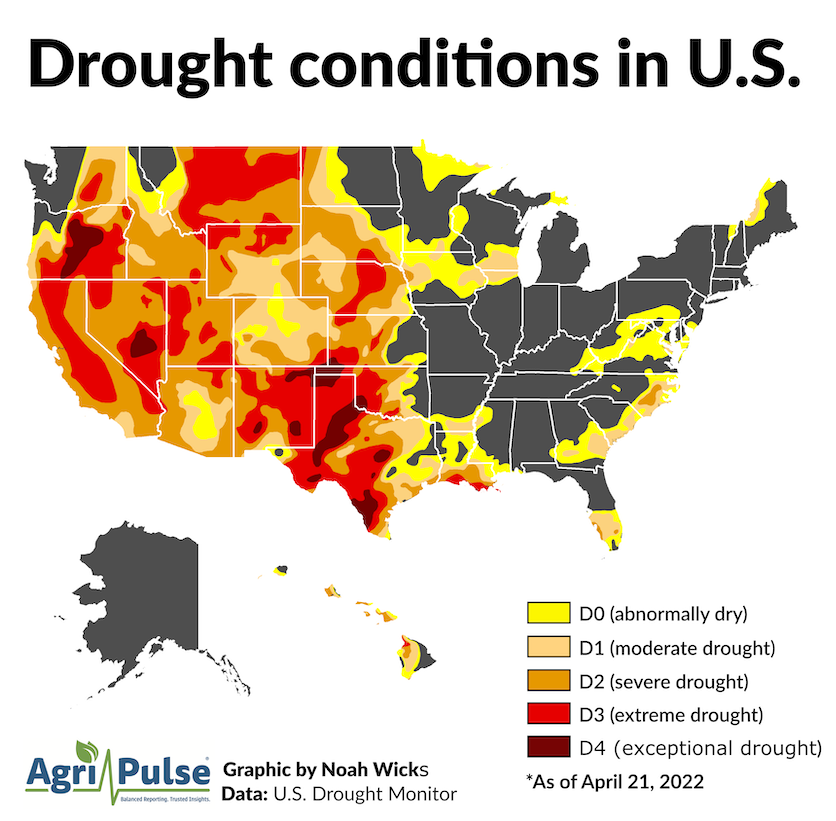

Swaths of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nevada, and Oregon are experiencing what the U.S. Weather Service calls "exceptional drought." This type of drought leads to major crop and pasture losses for farmers, a heightened risk of wildfire, and water shortages in reservoirs.

Several other regions, including California, Utah, Montana and Nebraska, aren’t faring much better, despite having slightly more moisture. These states are experiencing extreme drought, which can cause some crop or pasture losses, as well as widespread water shortages.

The drought is adding to concerns about a global food crisis triggered by Russia's war in Ukraine, a major supplier of grain.

"You are going to see from now on out for the next several months, a lot of volatility in the markets" because of the drought, said Joe Glauber, an economist with the International Food Policy Research Institute and former chief economist for USDA.

Glauber said it's too early to write off the winter wheat crops in the southern Plains because of the impact some timely rains could have.

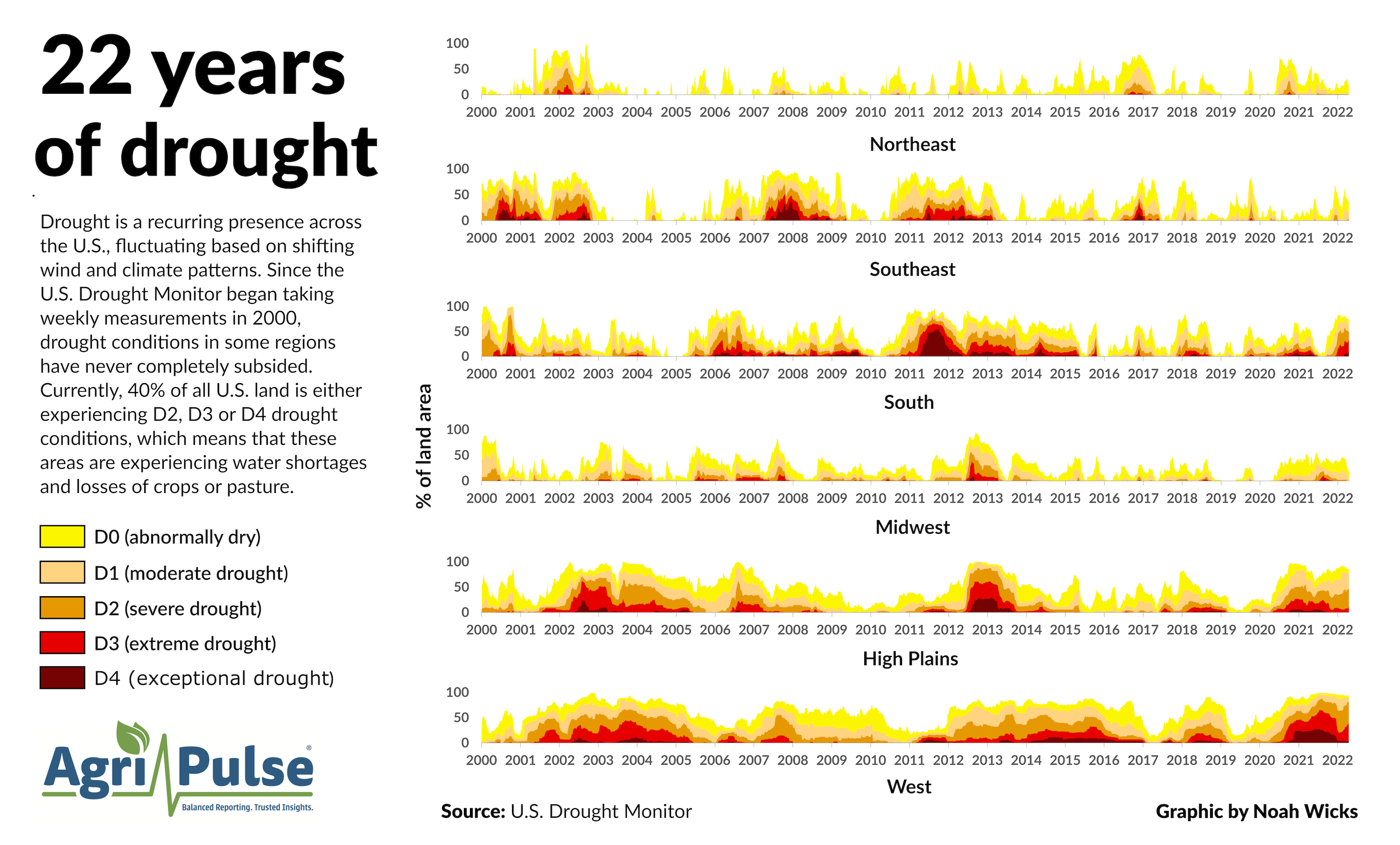

The conditions are partly linked to recurring weather patterns. Every three to seven years, waters in the equatorial Pacific cool, pushing the jet stream northward during an event known as La Niña. The result is warmer, drier weather in the South.

“We've seen more than twice the amount of normal drought in the U.S. for better than a year and a half and that's directly attributable to La Niña, which has been going on for more than two years now,” said Brad Rippey, a USDA meteorologist and the author of the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“Some of the latest guidance coming out from the National Weather Service and university researchers indicates that there's at least a fighting chance that La Niña could now last into and through a third consecutive year,” Rippey said.

These conditions are particularly noticeable in Texas, where producers are experiencing the driest September-to-March period they’ve seen since 1967, according to state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon. More than half the land in the state is seeing extreme or exceptional drought.

Some producers in Texas say this year’s conditions are reminiscent of those seen in 2011 when one of the state’s most destructive droughts led to over $7 billion in losses for farmers and dramatically shrank the state’s water reservoirs. According to the USDA’s latest crop production report for this year, just under 80% of the state’s winter wheat crop is rated very poor to poor, and many other crops have yet to be planted.

In the Texas panhandle, the annual rainfall in Tulia, where Irlbeck is located, ranges from between 18 to 22 inches a year. But Irlbeck says the region’s only gotten around seven-tenths of an inch since October.

“I want to make a crop, I don't want to get into the insurance game,” he said. “But that's what's probably going to happen a lot in our area. People are going to have to rely on insurance this year.”

Clint and Amanda Tolle, who raise wheat, soybeans, milo and cattle in north-central Oklahoma, did see snowfall during the winter. But heavy winds blew much of this moisture away.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

The Tollesons are planning to grow around 2,000 acres of wheat and 1,200 acres of soybeans this year, using both conventional till and no-till to spread out their risk. They plan to use fertilizer they purchased last November and December.

“We did a lot of pre-purchase contracts just to make sure we could lock in that price at a lower rate than what it was hopefully going to be and it turns out we did, I think, very well in doing that,” Amanda said. “That was a very smart business decision.”

In Oregon's Klamath Basin, a region where producers have historically relied on irrigation to cope with the dry climate, fourth-generation farmer Jason Flowers said the Bureau of Reclamation only plans to give farmers a fraction of the irrigation water they’ve historically been able to access.

Flowers and other producers in the region will need to compete for the 50,000 acre-feet of water the agency plans to give to farmers this year, a fraction of the 325,000 to 400,000 acre-feet they are allocated during non-drought years. Flowers usually is able to plant around 2,500 acres of grain, but because of water constraints, he’s only planning to plant around 500.

“A lot of the ground that we farmed in the past isn’t getting any water,” Flowers said. “It’s kind of forcing you to downsize, and when you’re set up for a certain size, being forced to downsize makes things difficult.”

The region has seen bits of rain throughout the previous weeks, Flowers said. But it is often the winter snowpack from the mountains that refills the state’s water reservoirs, and this year, the U.S. Forest Service estimates water levels from snowpack are only 58% of the historical average.

Flowers has not purchased fertilizer yet, but has been discussing prices and options with a local company. It would cost him over $150 per acre this year, more than double what he paid last year.

This cost, along with uncertainty over how long current high grain prices will last, is concerning to Flowers, who could easily see decreased yields due to the drought.

“It's kind of scary to me how insecure everything is right now,” he said.

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.