The San Joaquin Valley and its eight counties have long struggled with some of the nation’s worst air quality. Despite major strides over the decades, state lawmakers claim local air districts are moving too slowly and need more state oversight to pressure the agencies into meeting federal standards.

“This status quo is not acceptable,” said Fresno Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula, during a recent policy committee hearing. “In the face of a decades-long health crisis, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) must engage more strongly on this.”

Bakersfield, the Fresno region and Visalia top the list of cities with the most year-round particle pollution, according to the American Lung Association. Fresno County alone has more than 65,000 cases of adult asthma and nearly 20,000 cases of pediatric asthma, with about one in five children throughout the valley living with asthma. The bad air quality has adverse impacts to childhood development, leads to missed days of work and has both immediate ailments and long-term chronic conditions, according to Arambula, who worked as an emergency room physician before taking office.

He charged that the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District has not met federal standards for ambient air quality that were established 25 years ago.

“It is the state's responsibility to ensure that everyone—including our people who live in the San Joaquin Valley—can breathe cleaner air and not suffer from the impacts of pollution,” he said.

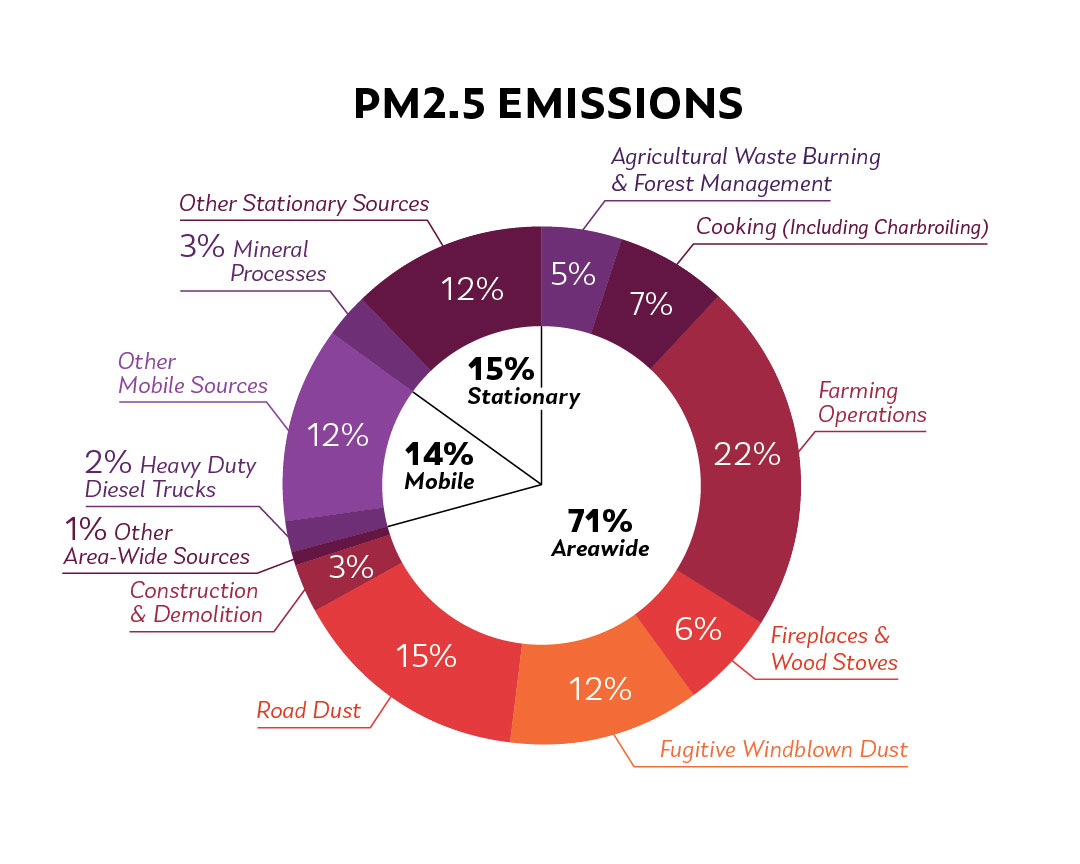

In 1959 California enacted legislation requiring the state Department of Public Health to establish air quality standards and necessary controls for motor vehicle emissions. California law continues to mandate California ambient air quality standards (CAAQS), which are often more stringent than national standards. Particulate matter emissions—along with several other categories of air pollution—are a concern in the San Joaquin Valley. In addition to PM10 and PM2.5 (shown above), the state monitors several other pollutants, with the largest source of all pollutants from the transportation sector. (Image: San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District)

To address this, Arambula has proposed a measure that would require CARB to take regulatory and enforcement actions in air districts that have fallen behind on air quality standards—in the valley as well as within nine other air districts.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

“More people in our region die each year from fine particle pollution than car accidents,” said Catherine Garoupa White, executive director of the Central Valley Air Coalition, a group advocating for more progressive action on reducing air pollution impacts to socially disadvantaged communities, such as by halting state incentives for dairy digesters. “Given the district's long history of favoring industry at the expense of public health, we continue to blow through deadlines to meet standards that are so old, they can no longer be considered health protective.”

White said Arambula’s Assembly Bill 2550 would create a middle path between “a complete takeover of the air district or the current hands-off review.” She believed AB 2550 would elevate the voices of community-based organizations and disadvantaged communities within the planning process for meeting air quality standards.

Yet Tom Jordan, a policy advisor for the valley air district, argued the proposal ignores CARB’s existing oversight authority and the collaborative approach it takes with districts. He added that it would not provide any additional resources to help the district meet its goals and it would impede progress by layering on new mandates.

The single largest source of emissions, he pointed out, comes from the transportation sector, which falls primarily under CARB’s authority, while air districts focus on stationary source emissions—and have slashed that pollution by 90%. Stationary sources make up just 15% of nitrogen oxide emissions, for example, and the rest comes from mobile sources.

The valley has also reached federal attainment for some categories of ozone and fine particulate pollution. The air district has also been considering ways to promote more widespread adoption of conservation tillage practices to reduce dust and fulfill a commitment in the its 2018 PM2.5 State Implementation Plan.

Arambula responded to Jordan’s assertions by returning to his initial argument that “our communities of color have felt the impact of this bad air pollution for far too long” and the state bears responsibility.

Jordan also suggested Arambula and White were misconstruing a recent lawsuit against the district, which was part of a string of claims filed by a coalition of environmental groups over the valley’s PM2.5 plan. EPA ruled in favor of CARB and the air districts for all areas but one, where it noted a shortfall of $2.6 billion in incentive funding.

“On the stationary source side, we met the requirement of having the most stringent measures,” said Jordan. “Our rules are more stringent than any rule anywhere else throughout the country.”

White, however, viewed the decision as showing the district has a history of relying too heavily on incentive dollars, which is like “throwing money in a black hole.” She said even with the strong rules, the district lacks the enforcement needed to control polluters.

Arambula persuaded enough lawmakers to support AB 2550 that it passed two committees along party lines. But it narrowly gained a majority approval on the Assembly floor last week, with several moderate Democrats choosing not to vote on the measure. The bill awaits a committee hearing in the Senate.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.