Lawmakers have given themselves another year to write a new farm bill, but they have a limited amount of time to reach bipartisan agreements on critical issues and could easily be forced to pass another extension of the 2018 law for another year at least.

The year-long extension of the 2018 farm bill enacted last week effectively gives lawmakers until January 2025 to finish a new bill. That’s when the expiration of the extension could trigger laws dating back to 1938 and 1949 that would force USDA to take steps next year to dramatically raise the price of milk, wheat and other commodities.

But lawmakers must make significant progress on a new bill in the first half of 2024. After the midway point of the calendar, the House and Senate are scheduled to mostly be out of session except for a few weeks between the Republican National Convention in July and the November elections.

Meanwhile, Congress is nowhere close to agreeing on aid for Ukraine and Israel, and a protracted partisan battle over fiscal 2024 appropriations could easily drag through March. After that, there could be another fight brewing on FY25 spending.

The hard deadline for Congress to agree on fiscal 2024 spending bills is effectively April. If lawmakers can't reach a deal, April is when a 1% across-the-board cut in spending would kick in under this spring's debt ceiling agreement.

“All this does not bode well for reaching an agreement on the farm bill other than another extension. I hope I’m wrong,” said Bill Hoagland, a congressional analyst with the Bipartisan Policy Center and former longtime GOP Senate aide.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)Because of the political calendar, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, says July is the effective deadline for Congress to get a new bill done.

“If there's a will to get a farm bill done anywhere through July I think it will get done. If there's not a will to get done, it'll be extended for one year … and then the new Congress starts over again,” he told reporters Tuesday.

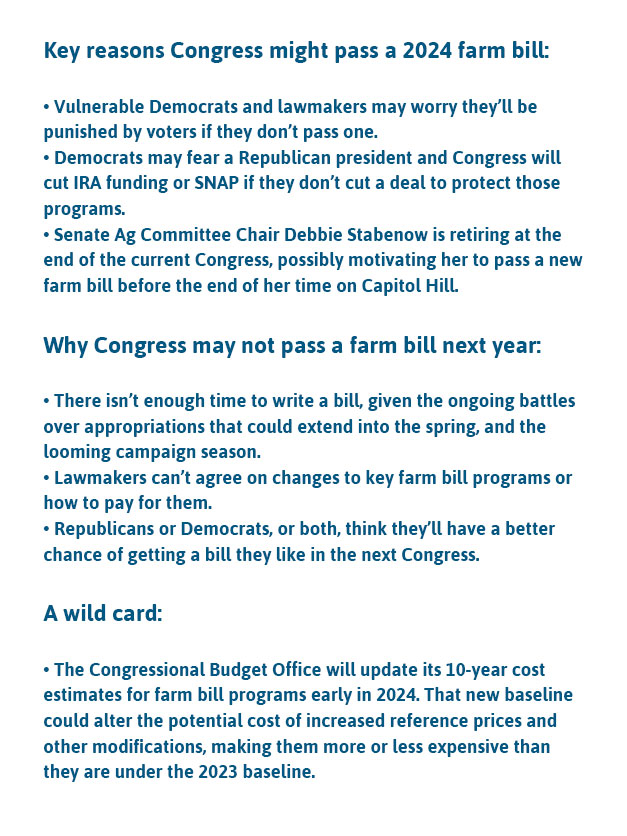

Congressional Republicans believe Senate Democrats and Ag Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, D-Mich., have plenty of motivation to pass a new farm bill.

Two incumbent Senate Democrats from farm states, Jon Tester of Montana and Sherrod Brown of Ohio, face tight re-election battles. With Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin retiring in West Virginia and that seat likely going Republican, either the Montana or Ohio race could decide which party controls the Senate, now controlled 51-49 by Democrats. Brown is a senior member of the Senate Ag Committee, while Tester is on the Senate Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittee that writes USDA’s annual budget.

“Farm country has been good to Republicans,” Sen. John Boozman, the ranking Republican on Senate Ag, told Agri-Pulse. “Republicans, they respect that … so there's an incentive to get [the farm bill] done. Farm country has also been good to Democrats in critical areas, both in the House and the Senate. Democrats understand that.”

Republicans also are counting on Stabenow, who's retiring in 2024, wanting to negotiate a new farm bill that would provide some protections for conservation and nutrition funding after she leaves the Senate.

Republicans would like to cut a deal with her to reallocate conservation program funding provided by the Inflation Reduction Act and reduce the cost of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program by restricting how USDA calculates future benefits through updates of the Thrifty Food Plan, an economic model for food costs. Savings from SNAP, Republicans argue, could then be plowed into other areas of the farm bill.

But Stabenow has so far refused to consider such restrictions on TFP updates and insists on keeping IRA funding devoted to climate-related practices. There’s no sign Republicans have identified any other funding sources for the farm bill that will have Democratic support.

Stabenow told reporters ahead of the Thanksgiving recess she is eager get a farm bill "as soon as possible" next year, although she suggested the ongoing appropriations process could delay lawmakers getting to the legislation.

She said she wants to "hear more in terms of a sense of urgency" from farm groups. "They certainly have given us their priorities. We've heard them loudly and clearly," she said.

Privately, however, she and her staff have told Republicans it's not critical to her that a new bill passes before she retires, in part because she secured the IRA funding in 2022, and USDA implemented the TFP update in 2021, according to a Capitol Hill source close to farm bill discussions. Stabenow won a requirement for regular TFP updates in the 2018 farm bill.

But without a bipartisan agreement on funding, talks on a farm bill likely won’t get any further in 2024 than they have in 2023. Stabenow said she has identified $4 billion to $5 billion in funding outside the farm bill, but she hasn't disclosed its source, and that's not nearly enough to make the changes in commodity programs Republicans have been pushing.

“The same issue that's been there for the last year still is there, and that is that they have not identified any additional resources that they could bring to the table and that's the problem. And until they get that and get some certainty that people agree on what it is, you can't really move forward,” former House Ag Committee Chairman Collin Peterson, D-Minn., told members of the National Association of Farm Broadcasting last week.

It’s easy to be “in the know” about what’s happening in Washington, D.C. Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! Simply click here.

In the past, the House GOP would have simply ignored Democrats and funded the farm bill with IRA or SNAP funding and passed a partisan bill with no Democratic support.

But Republicans currently control the House 221-213, giving them a four-vote margin to move partisan bills; that cushion could shrink to just three votes as soon as next week with Rep. George Santos, R-N.Y., facing an expulsion vote.

“You have the narrowest House majority in modern history, [the farm bill] has to be bipartisan,” said Tyson Redpath, a farm policy lobbyist and former House GOP leadership aide.

Several hardline GOP conservatives who are members of the House Freedom Caucus expressed frustration that the new year-long extension would keep them from using the farm bill to get votes on farm bill reforms, including cuts to SNAP.

“We got no policy changes out of it,” Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, said of the extension. He doesn’t expect the House to pass a farm bill next year either. The farm bill “is going to get kicked down the road again, so it’s really more like a two-year extension,” Roy told reporters.

The inability of House Republicans to pass their own partisan appropriations bills has also raised questions about their ability to move other legislation.

Last week, GOP leaders had to pull two more FY24 spending bills from the floor. One of the bills didn’t have enough votes to pass. In the other case, GOP hardliners voted with Democrats to tank the rule that was needed to bring the bill up for debate.

“If we've got people who refuse to be a part of a team, then it's going to be hard to get much done in the House,” Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-S.D., said of his hardline conservative colleagues.

Johnson expects a large number of Freedom Caucus members to oppose any farm bill, making Democratic support critical.

Former House Ag Chair Collin Peterson, D-Minn.

Former House Ag Chair Collin Peterson, D-Minn.“This is just a harder environment than normal,” said Rep. Frank Lucas, an Oklahoma Republican who chaired the House Ag Committee when the 2014 farm bill was enacted. “Yes, it's going to be challenging. Yes, I'm frustrated. But we are where we are.”

If Congress is ultimately unable to pass a new farm bill next year, there will be at least one key new player: Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., is expected to take over for Stabenow as the top Democrat on Senate Ag in 2025. She’s been an ally of Midwest farm groups on a range of issues, especially biofuel policy.

“Amy is teed up. She wants to do this,” Peterson said of Klobuchar and the Senate Ag leadership. “I spent a lot of time schooling her. She's got a good understanding of ag policy. … She may not be the chairman. She might be the ranking member. But who knows what's going to happen in these elections."

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.