States are trying to meet land conservation goals and protect agricultural acreage, but securing enough money – and enough land – to do that has been difficult across the country.

For the past two decades, the state of North Carolina’s Ag Development and Farm Preservation Trust Fund has protected 30,000 acres using permanent conservation easements to prevent the land from being developed for anything but agriculture and open space.

The good news: That’s a lot of land. The bad news: More than 1 million more acres in the state are at risk of being lost to development by 2040, according to an American Farmland Trust projection for the state in its Farms Under Threat 2040 report.

How does a state preserve that much land in the next 16 years?

“It’s going to be difficult,” says Evan Davis, director of the North Carolina Ag Department’s Farmland Preservation Division. “Under the current development trends, we’ll lose 1.1 million acres by 2040.”

North Carolina can reduce that number by building cities up rather than out with more density and focused zoning efforts, Davis noted. But even those efforts, along with increased funding for conservation easements, won’t mitigate even half the losses.

“In the best-case scenario, we’re still looking at 600,000 acres of farm, timber and ranchland being converted,” Davis says.

While North Carolina is facing some of the biggest losses – AFT estimates only Texas is projected to lose more – they aren’t alone. The AFT report estimates more than 18 million acres of farm and ranch land nationally will be lost between 2016 and 2040, an area roughly the size of the state of South Carolina.

The threat of converting ag land to other uses has many states redoubling their efforts to get more land under conservation easements of some type – easements that prevent the land from being developed outside of agricultural purposes.

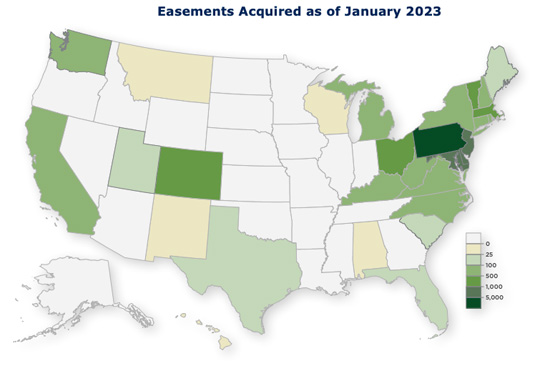

According to AFT, 28 states administer 36 active purchase agricultural conservation easement programs (PACE). The longest standing state PACE programs are clustered in the Northeast (Massachusetts and Maryland authorized programs in 1977).

Jennifer Dempsey, AFT

Jennifer Dempsey, AFT“More states, including those with relatively large supplies of agricultural land, are recognizing the threat to their agricultural resources,” Jennifer Dempsey, director of AFT’s Farmland Information Center, said. There is a new authorization in Georgia and legislation is being considered in Illinois.

State-level PACE programs have invested more than $5.2 billion in state funds to acquire more than 19,000 easements on more than 3.5 million acres in 30 states, according to Coffin. Other partners such as federal agencies, foundations, and individuals have spent an additional $3.1 billion to complete these projects.

When state-level programs are considered along with private land trusts and federal programs, nearly 8 million acres of total farm and ranch land have been protected under permanent easements, according to AFT. Cris Coffin, director of AFT’s National Agricultural Land Network, credits the Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in 2022, with allocating an additional $1.4 billion to the USDA’s Agricultural Conservation Easement Program.

“This will make conservation easements an option for many more farms, ranchers, and rural landowners looking to protect their land,” Coffin said.

In some cases, the promotion of state programs is working. North Carolina is currently reviewing 100 grant applications for funding this calendar year after receiving 46 in 2023. The newest applications encompass 12,000 acres and $39 million in grant funds, according to Davis. In 2023, the 46 applications were funded at $17 million.

“Our year-over-year goal is to increase acres in easements by 10%,” Davis said. “We already have about 34,000 acres under easement protection so that means we want to add 3,400 acres this year.”

It’s easy to be “in the know” about what’s happening in Washington, D.C. Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! Simply click here.

USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service has its own Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, created in 2014. ACEP combines three formerly separate programs: the Grasslands Reserve Program, Wetland Reserve Program, and the Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program. NRCS works with state, local, tribal, and private nonprofits such as North Carolina’s Ag Development and Farm Preservation Trust Fund to defray the costs of easements. ACEP has more than 5 million acres nationally under easement.

In many cases, ACEP will match 50% of the cost of the easement through an application from, for example, a private nonprofit like The Land Trust for Tennessee.

The Texas Agricultural Land Trust, created 17 years ago, has protected nearly 50 family farms or ranches encompassing 300,000 acres. A private nonprofit, the trust largely relies on federal money via NRCS to help purchase easements, all of which are held by the trust. The trust also received some funding from the Texas Farm and Ranch Land Protection Program, which has allocated $2 million for easement acquisition every two years for the past eight years.

“Right now our limitation is funding,” says Darren Clark, TALT’s chief operating officer and director of land conservation. There had been a push in the state last year to allocate $1 billion toward the effort, but “at the very end it got squashed,” he noted. Then, it appeared as if there was legislative support to increase the $2 million biennial allocation to $10 million. That measure fell short of approval in the Texas House of Representatives.

Clark points out the AFT report estimates Texas lost 360,000 acres of farm and ranch land to some type of alternative use or development in 2023.

“After 17 years in existence we’re just now reaching 300,000 acres protected,” says Clark. “That doesn’t even offset one year of what Texas loses in one year.”

The desire to conserve farmland is, more often than not, about the emotional desire of people to preserve family land as it is rather than the consideration of any financial benefit for doing so.

“Many people want to be able to keep the land in the family,” noted Jackson Lundy, conservation project manager of the Land Trust for Tennessee, a statewide nonprofit conservation organization. “There are memories associated with the land and a lot of people are tied to that sense of place.”

Map: American Farmland Trust

Map: American Farmland TrustThe LTT has helped put 136,000 acres under conservation easement since 1999 with 455 separate projects. In most of those cases the trust remains the “holder” of the easement, responsible for ensuring the land remains in compliance.

A permanent or conservation easement is essentially a legal commitment that the property won’t ever be developed beyond specified uses. Once in an easement, the development value of the land is reduced, which may reduce the amount of property tax owed.

In addition, landowners that donate a permanent easement may be eligible for tax incentives equivalent to the diminution in value, according to Lundy. “The incentive may be carried forward for up to 15 years against adjusted gross income,” he said.

In some cases – depending on the state and organization involved – landowners putting property in a permanent easement may receive cash payments to compensate them for the loss in the land’s value. This payment, usually based on an appraisal, has helped farm and ranch families expand or improve their operations, as well as pay down debt or transfer their land to the next generation.

“The tax incentive is probably used in only about 50% of the easements we’ve worked with,” Lundy said. Most of the landowners there simply want to keep the land in the family and aren’t concerned about the tax benefit.

The state leader in permanent easements is Pennsylvania, where the state’s Farmland Preservation Program began in 1988. The state has helped protect 6,314 farms consisting of more than 630,000 acres. At least part of the program’s success is because the state pays landowners for the easements. In 2023 alone the state spent $46.3 million to protect 166 farms and has spent $1.69 billion since 1989.

“There’s extreme pressure on farms to be sold for development because of the value of the land,” says Shannon Powers, press secretary for Pennsylvania’s Department of Agriculture. “The program has been extremely popular since 1988 and there’s been commitment at every level of government, from federal to state to local for this program.”

Some of the Pennsylvania easements are held by the state when state money alone is used to purchase the easement. In other cases where county, municipality or private funding are involved, the county owns the easement. In all cases, county farmland preservation programs do follow-up inspections on preserved farms in their counties to ensure that the terms of the easement are followed.

While the money allocated to programs such as North Carolina’s Ag Development and Farm Preservation may not be climbing fast, the state is continuing to promote the saving of land. Last year, in addition to the NC Forever Farms initiative, they are also promoting Agricultural Growth Zones as targets for conservation easements.

“We want to do preservation projects in certain areas that affect ag communities or may be vulnerable to urban or suburban sprawl,” North Carolina’s Davis said. The idea is to create concentrated areas of conservation – a critical mass of farmland – to prevent a fragmented landscape.

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.