Thousands of producers hoping to implement more conservation practices on their farms are lining up for government assistance through the Environmental Quality Incentives and Conservation Stewardship programs, as the Agriculture Department touts the promises of climate-smart agriculture as a mitigator of climate change.

But these programs, despite their billion-dollar budgets, aren’t equipped to deal with the demand, forcing the agency to turn away the majority of applicants.

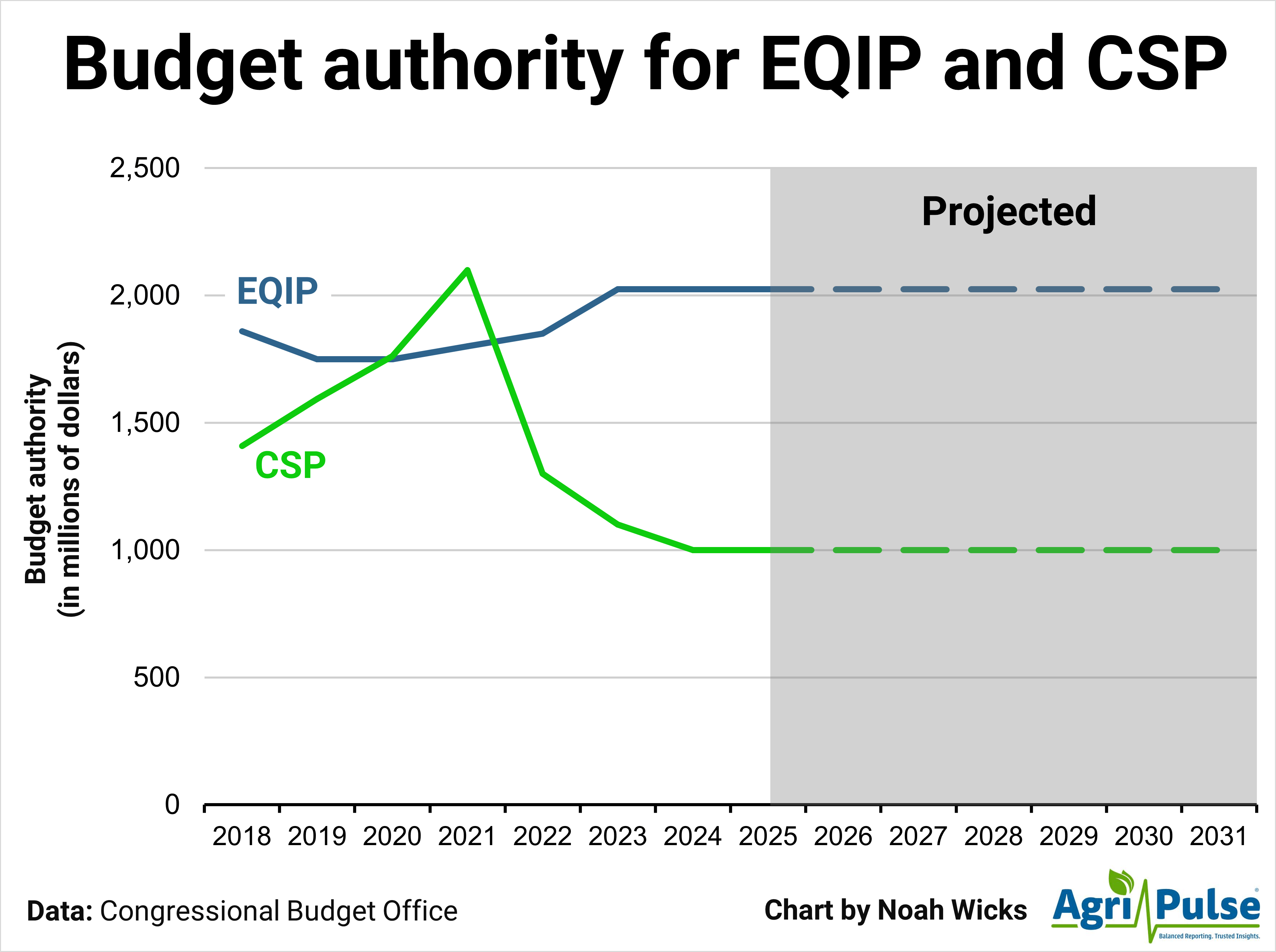

EQIP, bolstered in the 2018 Farm Bill with a 10-year budget increase of more than $1 billion, was only able to accept 27% of the 33,701 farmers who applied for contracts in 2020, according to statistics compiled by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, an agricultural think tank. CSP, which actually saw its 10-year budget reduced by $409 million in 2018, only awarded contracts to 25% of its 27,110 applicants in 2020.

“It's a pretty competitive process,” said Natural Resources Conservation Service Chief Terry Cosby, who oversees the agency in charge of the programs.

Congress first established EQIP in the 1996 farm bill, merging other conservation programs that existed at the time. With a $130 million budget, the program authorized NRCS to “provide technical assistance, cost-share payments, incentive payments and education” to producers who signed contracts promising to implement new environmental practices on their operations.

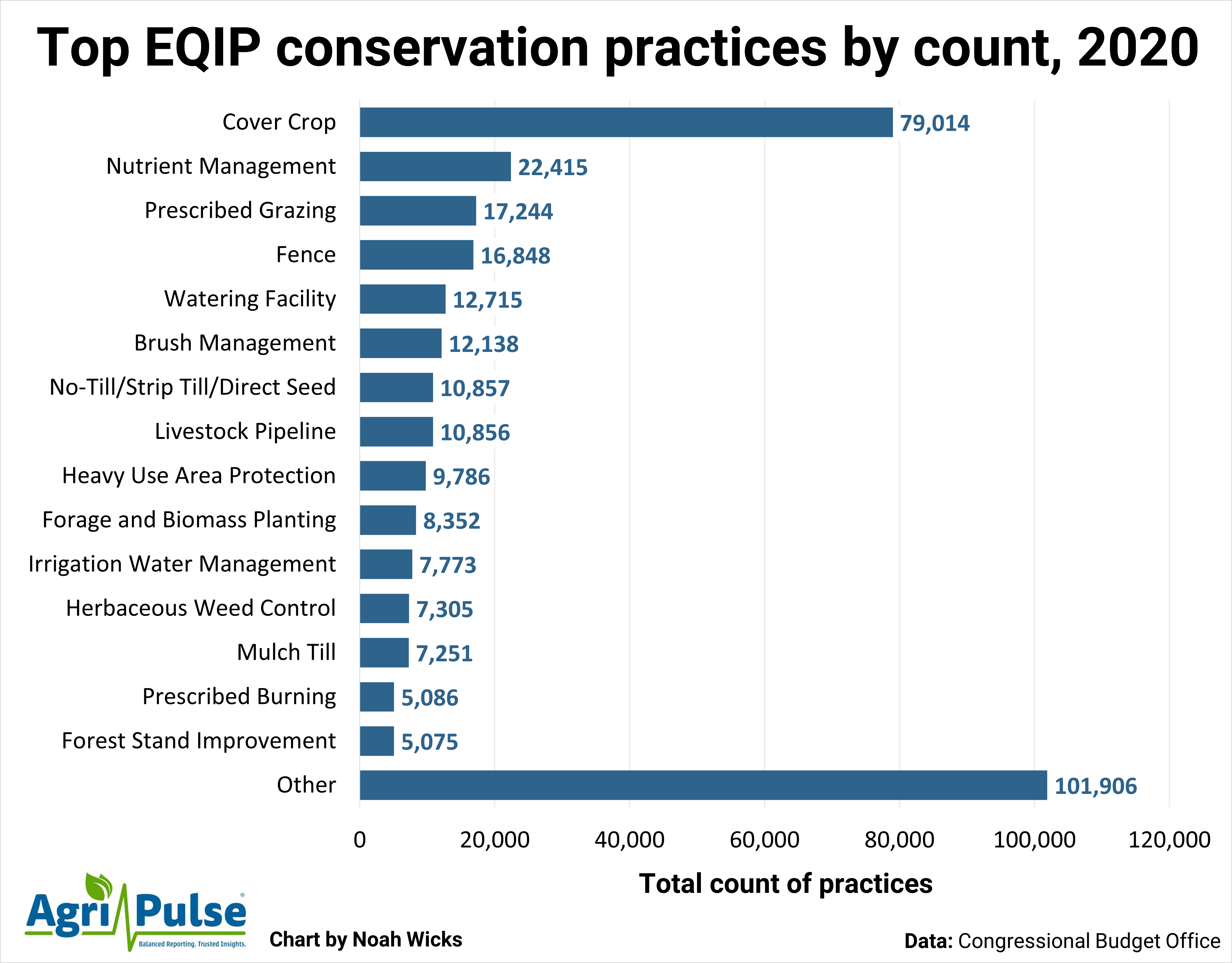

Since then, the program has ballooned in size, using billions of dollars to offer producers one- to 10-year contracts for adding new farming techniques like cover crops, no-till and prescribed grazing, or for buying new fencing and irrigation equipment.

But this money needs to be allocated to all 50 states, while also following specific instructions laid out in the 2018 farm bill. Half of it needs to go toward livestock operations, at least 10% must be dedicated to wildlife habitat, and 10% toward source water protection. Another 10% is split evenly between socially disadvantaged farmers or ranchers and beginning farmers and ranchers.

Cosby told Agri-Pulse that under NRCS’s current $1.8 billion budget the agency is only able to fund about 25% of the applications that come into each state. The program’s allocations are projected to increase to a peak of $2.2 billion by 2023, however, which should allow more producers access to the program.

“Unfortunately, we're not able to fund every contract,” Crosby said. “We're hopeful that as more funding becomes available, we'll be able to do that.”

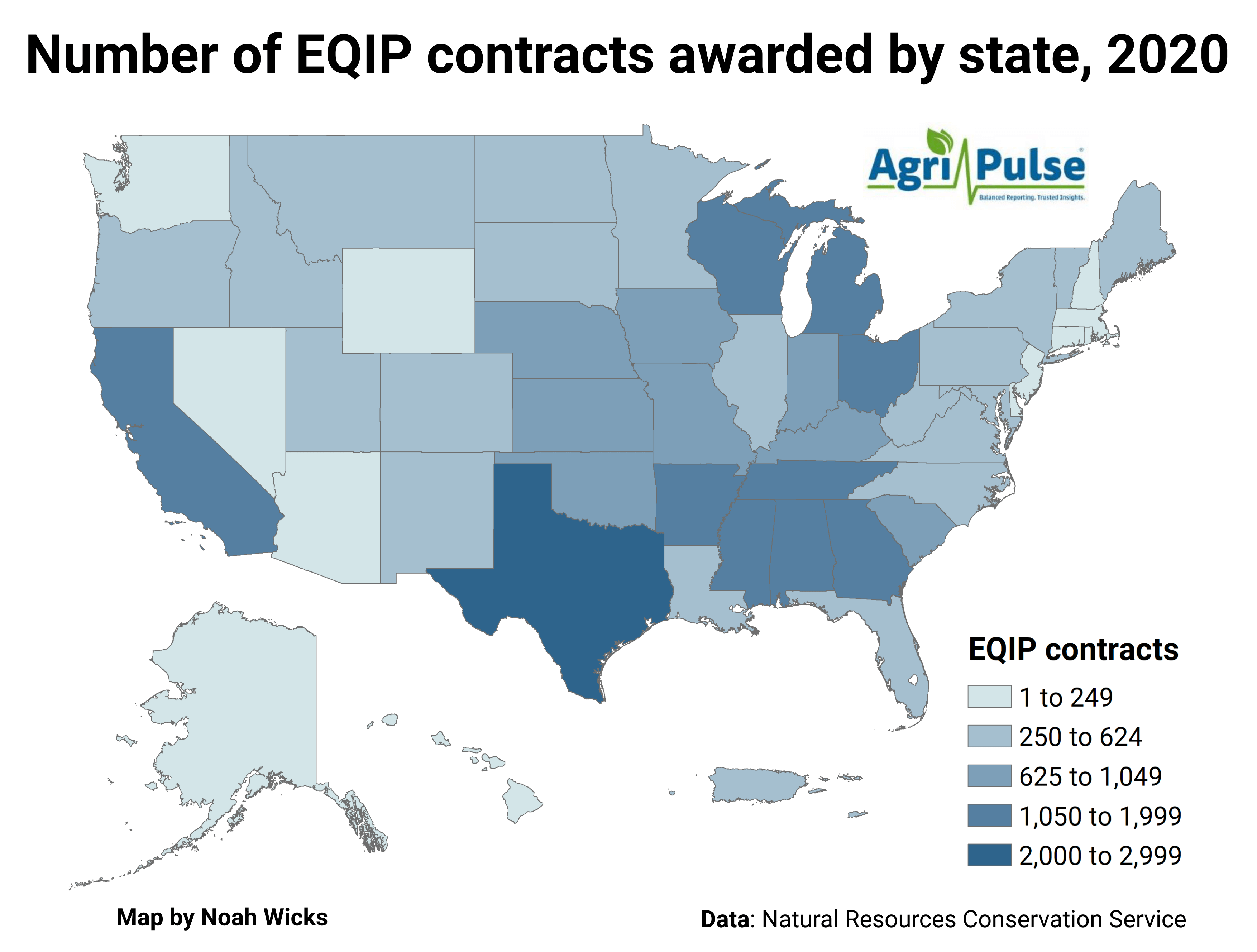

California and Texas were allocated the most EQIP funding in 2020, while small states like New Hampshire and Rhode Island were given the least, according to an Agri-Pulse analysis of NRCS data.

California’s NRCS office received $121 million in 2020, which helped fund the 1,473 producers that signed contracts in the state. Texas, which signed 2,991 contracts with producers, was given $120 million.

California’s NRCS office received $121 million in 2020, which helped fund the 1,473 producers that signed contracts in the state. Texas, which signed 2,991 contracts with producers, was given $120 million.

New Hampshire and Rhode Island, on the other hand, only received $6.7 million and $4.6 million, respectively. New Hampshire’s NRCS office awarded 266 contracts to producers in 2020, while the office in Rhode Island awarded 105.

One EQIP contract, voluntarily entered into by farmers, can cover a certain practice or the purchase of certain items specific to that farm. Hunter Carpenter, senior director of public policy at the Agricultural Retailers Association, said it is important for the program to keep its voluntary and farm-by-farm approach in the future.

“These programs need to adapt or be adaptable to what the farmer's needs are on that particular field,” Carpenter said. “These programs are not one size fits all.”

Cover crops were by far the most popular practice used by farmers in the EQIP program in 2020, with 79,014 contracts being awarded to fund them. Nutrient management practices were covered by 22,415 contracts, while prescribed grazing, fencing and installing watering facilities were the focus of 17,224, 16,848 and 12,715 projects, respectively.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

Producers can submit an EQIP application at any time, but to have a shot at securing timely funding, they must do so before state-specified cutoff dates. Their applications are then ranked by criteria developed by their state NRCS conservationist, with contracts going to the applications with the highest rankings.

But EQUIP’s budget limitations leave many producers who already went through the often-lengthy process of applying – including some who already started working on their projects – without a contract.

“To have to wait months and months and then find out that it just hasn’t been funded is a challenge,” said Jorgen Rose, the habitat and policy viability manager at Practical Farmers of Iowa. “It’s frustrating for producers.”

CSP, which was created in the 2002 farm bill and then overhauled and renamed in 2008, is geared more toward producers who have already implemented some conservation practices in previous years and are looking to expand to using more.

The program typically requires a longer-term commitment than EQIP, with producers signing five-year contracts for not only maintaining conservation practices that have already been established, but for adopting new ones as well. While EQIP usually pays for one practice after it has been completed, CSP provides annual payments throughout the contract time period.

“It's kind of a unique thing among programs — to get people to think about the whole farm reality of their conservation efforts and look at tons of different ways to tinker with that,” said Jesse Womack, a policy specialist at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

But the CSP’s effectiveness has been a consistent point of debate during previous farm bills, with House Agriculture Committee members even proposing to eliminate the program in 2018. While the program was ultimately kept alive in the final version of the bill, it saw a decrease in its overall budget.

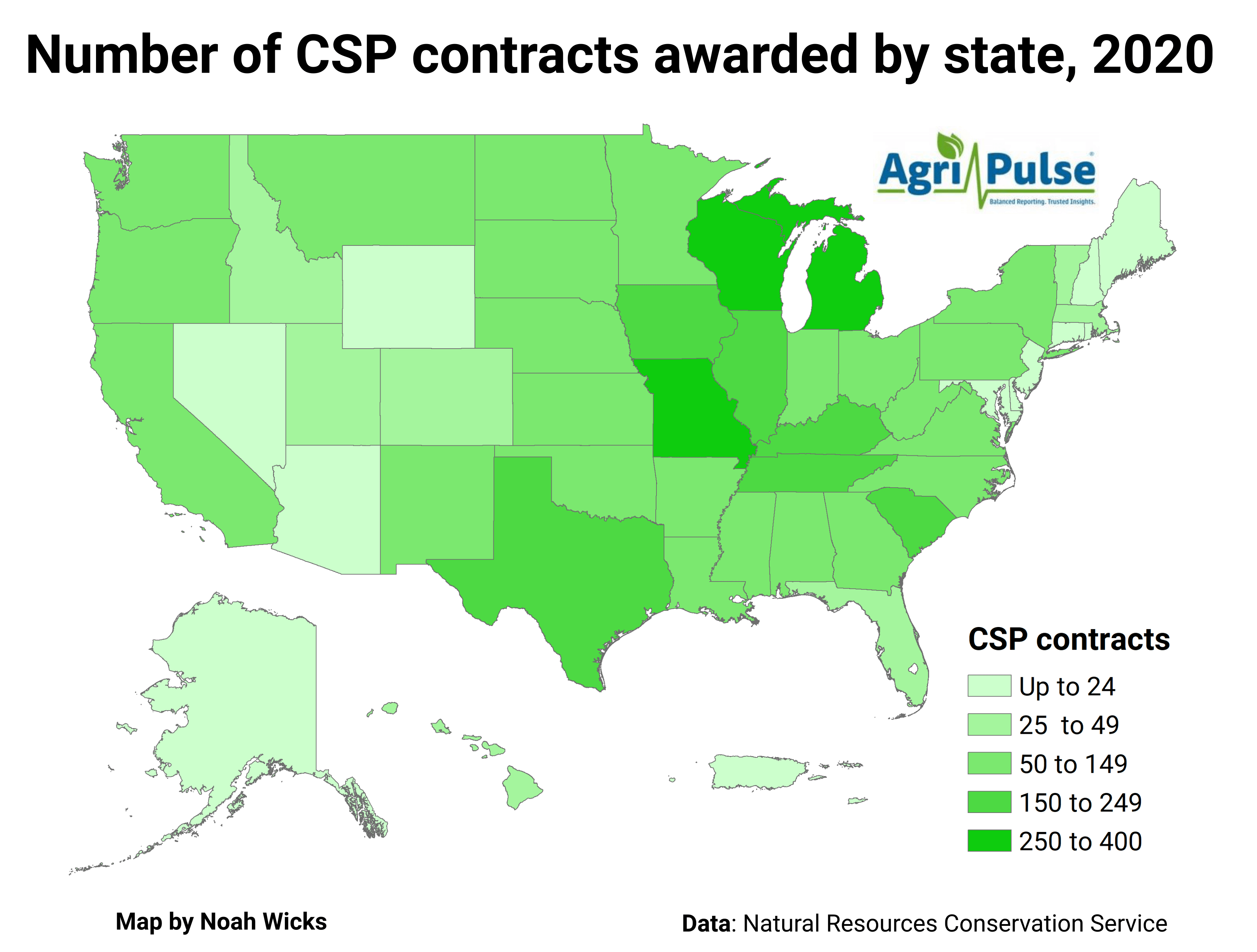

South Dakota, Arkansas, Mississippi and Minnesota received the most CSP funding in 2020, while Connecticut, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and New Jersey received the least.

Over $203 million was allocated to South Dakota that year for 90 contracts, while Mississippi was given $188 million for 114 contracts. Mississippi and Arkansas both received around $170 million and had 114 and 101 contracts, respectively.

In contrast, New Jersey was allocated the least funding, with $643,300 going toward four contracts. Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, both overseen by NRCS’s Caribbean office, were given a combined total of $754,800 for 10 contracts, while New Jersey received $796,200 for four contracts.

Rose said the competitive ranking system CSP uses can get frustrating for farmers who can't come up with new practices to try on the farm and, as a result, have a smaller chance of securing program funding.

"They basically run out of new things to do on the farm, so they can't rank high enough to get a renewal or do a CSP contract in the first place," Rose said.

With both programs facing a growing backlog, groups like Practical Farmers of Iowa, the National Milk Producers Federation and the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition told Agri-Pulse they want to see Congress increase their funding in next year’s Farm Bill.

“We're really concerned to see pretty dramatic levels of oversubscription that have risen after the 2018 farm bill,” Womack said. “That really seems like we're not putting our money where our mouth is in terms of supporting farmers that are ready to do good conservation.”

The Agricultural Retailers Association, however, wants Congress to take a closer look at why that backlog exists before deciding on a solution. The group, according to Carpenter, also supports increasing program payments at a rate consistent with inflation.

“We've seen record inflation numbers the past couple years and it seems to be getting worse,” Carpenter said. “We do think that those payments going to farmers should reflect that.”

As Congress continues to focus on climate-smart agricultural practices, NMPF also wants lawmakers to add more options for livestock producers, who are looking to lessen the environmental impact of their feed and manure management systems.

“Our farmers have been using NRCS programs, but half the offerings haven’t really focused on the areas of manure management and feed management, which will have a big impact on reducing carbon emissions and greenhouse gas emissions in general for dairy,” said Paul Bleiberg, senior vice president of government relations. “So we think there’s a lot to be done to address some of these shortfalls.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.