WASHINGTON, April 22, 2015 – A fight by California dairy farmers and their co-ops for a better deal in the milk market will probably come to a head by year’s end, sparked by their move to ditch a state system that has guided their market for 48 years and, instead, form a federal milk marketing order in the state.

In February, the three biggest cooperatives that operate in the state – California Dairies, Dairy Farmers of America, and Land O'Lakes – with backing from other dairy farmer groups, such as Western United Dairymen and the statewide Milk Producers Council (MPC), asked USDA to create in their state what would be the nation's 11th federal marketing order. The request came months after the producers pressed, but failed, in the California Legislature to retool the existing system to their liking.

“After exhausting our efforts in California with hearings, protests, rallies, a lawsuit and

Legislation, the federal milk marketing order system is our best chance of putting California producers on an even playing field with our fellow dairies throughout the country,” says MPC Chief Executive Rob Vandenheuvel.

Billions of dollars are at stake: The state accounts for more than 20 percent of U.S. milk output – worth at least $7 billion a year as raw milk – with 85 percent of that state's production made into cheese, milk powder, butter and whey, and much of that output exported.

The co-ops have reached first base in their effort. That is, USDA received their request and will hold three public outreach meetings in May to clarify the process of creating a federal order and discuss the cooperatives' proposal along with alternatives. These include a proposal by the Dairy Institute of California, which represents the state's dairy processors and opposes the co-ops' plan, plus others such as one by the California Producer Handlers Association, which represents private dairies that produce and process all of their own milk. USDA may then decide to hold a formal hearing, perhaps late this year, on creating a marketing order.

Here is what the major players want, according to their proposals which are posted on the USDA web page dedicated to the California dairy issue. John Newton, a dairy expert at the University of Illinois, provides a neutral assessment of the proposals here.

First there is a sharp disagreement on whether federal law allows USDA to set up a milk marketing order in California. The Dairy Institute says the co-ops lack a legal basis for their request because the purpose of the 1937 law authorizing such orders is to “establish and maintain . . . orderly marketing conditions for any agricultural commodity.” Rachel Kaldor, the Institute's executive director, says USDA's historic purpose in creating the orders “was to prevent destructive marketing practices and create stability in the marketplace.” The existing California milk marketing system isn't disorderly, she says. On the other hand, Vandenheuvel notes the law is also intended to “ensure an adequate supply of milk,” which must assume that dairy farms survive economically.

First there is a sharp disagreement on whether federal law allows USDA to set up a milk marketing order in California. The Dairy Institute says the co-ops lack a legal basis for their request because the purpose of the 1937 law authorizing such orders is to “establish and maintain . . . orderly marketing conditions for any agricultural commodity.” Rachel Kaldor, the Institute's executive director, says USDA's historic purpose in creating the orders “was to prevent destructive marketing practices and create stability in the marketplace.” The existing California milk marketing system isn't disorderly, she says. On the other hand, Vandenheuvel notes the law is also intended to “ensure an adequate supply of milk,” which must assume that dairy farms survive economically.

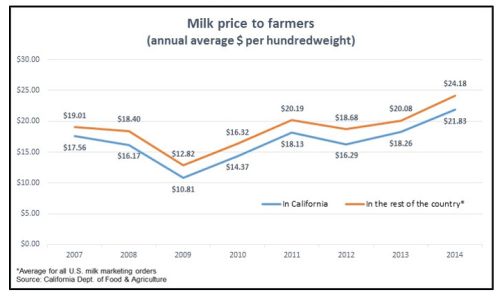

The co-ops are focused on their take-home receipts. They point to the net prices producers in the federal marketing orders receive: usually 10 percent higher than for California farmers (see chart below). They complain that the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) assures processors of a fair margin in making dairy products, but sets prices for all classes of milk, whether for drinking or processing, too low for farmers to survive. Owing in part to several recent years of drought and high costs of forage and feed, the actual milk price paid to California farmers has been lower than the CDFA's estimated cost of milk production in two-thirds of the months in the past eight years, Vandenheuvel says.

There is a fundamental reason for California milk prices to be lower overall than in other states. In both California and in federal orders, milk for drinking, called Class 1 milk, gets the highest prices; milk for processing gets lower prices. Milk receipts within an order are pooled, so farmers operating in marketing orders with a greater proportion of Class 1 milk, such as the one for Florida, net higher prices. California, which uses 85 percent of its milk for processing, will by necessity have lower net prices under such pooling systems.

Nonetheless, the California co-ops point out that their price for Class 4b milk, used to make cheese and whey, is also consistently 10 percent to 15 percent lower than the average paid for the same class of milk in federal orders.

If USDA does proceed to a full hearing on creating an order, several aspects of pooling and pricing California milk will be in contention, even though Congress, in the 2014 farm bill, instructed USDA to retain some form of the milk marketing quotas now embedded in the California system. One big source of conflict: In a federal order, milk that falls into the processing classes can be sold outside the order and at any price so the market is cleared and surpluses are avoided. In California, all milk must be sold at or above state minimum prices, so the state must set prices low enough for processing milk supplies to clear.

The cooperatives want to lock in all milk in their federal order at minimum prices. The Institute's Kaldor says that doing so would be outside the structure common to the federal orders. “In federal orders, a lot of milk is sold under the class prices,” she says, and a marketing order without that option would defeat its own purpose of maintaining an orderly market.

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.