WASHINGTON, Sept. 13, 2017 - As Congress prepares to write a new farm bill, analysts are raising questions about the Price Loss Coverage program and the fairness of its price guarantees.

About 49 percent of the total farm safety net payments, including crop insurance, have been on corn - the nation's largest crop - compared to 16 percent for wheat, 15 percent for soybeans, 8 percent for cotton, 5 percent for rice and 4 percent for peanuts, according to the Congressional Research Service. But a lot of the money that went to corn, soybeans and wheat was provided through the Agriculture Risk Coverage program, and farmers are expected to shift wholesale to PLC because of the way it is structured.

PLC triggers payments when commodity prices fall below fixed reference prices. ARC provides subsidies only when county revenue falls below a rolling five-year average, and at current projections it’s unlikely to trigger many payments in coming years.

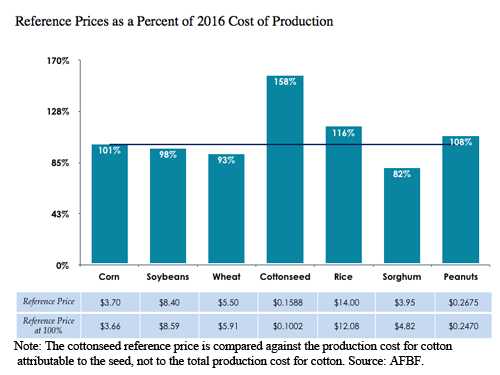

But new analyses by CRS and the American Farm Bureau Federation suggest that the PLC reference prices are significantly more favorable to some commodities, especially rice and peanuts, than to others, such as wheat and soybeans. The studies also conclude that the reference price that cotton growers proposed for cottonseed, $15.88 cents per hundredweight, also would be significantly higher than the price guarantees of most commodities now in the program.

Mary Kay Thatcher, Farm Bureau

Some commodity groups are already appealing to Congress to raise the PLC prices in the new farm bill. Mary Kay Thatcher, a veteran farm bill lobbyist with AFBF, said there “is a lot of interest in looking at reference prices, where they are and where they are likely to be.”

David Schemm, a Kansas farmer who is president of the National Association of Wheat Growers, told the Senate Agriculture Committee in July that the PLC reference price for his crop should be raised from $5.50 to $7 a bushel “to truly enable PLC to function as a safety net for farmers when times are tough, like they are today.” He said the current price is far below the cost of production, a claim that is backed up by the latest analyses.

The National Sorghum Producers, meanwhile, wants Congress to increase all the reference prices and index them to production costs. PLC is the “most relevant, most reliable, and most complementary to other policies like crop insurance,” said Jennifer Blackburn, a spokeswoman for the group.

The AFBF analysis shows why those groups think higher rates are justified. The reference price for rice is 16 percent higher than the average cost of production for the crop in 2016 and 19 percent higher than the average production cost for the past 10 years, according to AFBF. The reference price for peanuts is 8 percent higher than the cost of production last year.

By comparison, the reference price for wheat is 7 percent below the cost of production for that crop in 2016 and 21 percent lower than the 10-year average production cost. The reference prices for corn and soybeans are 1 percent above and 2 percent below the 2016 average production cost, respectively. Sorghum’s reference price is 18 percent below the average production cost last year.

The AFBF analysis goes on to project what the reference prices would be if they were set at a rate that would just cover farmers' total production costs, variable and fixed: If the prices were set at 100 percent of the 10-year average cost of producing a crop, wheat’s reference price would have to be raised from $5.50 a bushel to $7, while the rate for cottonseed would be set at $13.54.

The rate for rice would be slashed from $14 per hundredweight to $11.81 and the peanut reference price would drop from $26.75 per hundredweight to $24.17. The reference price for corn would be increased 26 cents to $3.96 a bushel. The rate for soybeans would be raised 42 cents to $8.82.

The disparities in the target prices largely reflect the politics of the 2014 farm bill. The National Corn Growers Association and American Soybean Association were primarily focused on development of ARC, which was expected to trigger payments as prices tumbled from the spikes in 2012 and 2013. Peanut and rice growers favored the PLC program. "Reference prices weren’t as high as they could have been for the feed grains because of the national organizations," said one congressional aide who worked on the 2014 farm bill.

The House Agriculture Committee, which developed PLC, relied heavily on production cost information from Texas A&M University's database of representative farms.

Analysts with CRS asked what would happen if the reference prices were adjusted according to monthly average prices for each crop. If the rates were adjusted so that they fell below monthly market prices at least 40 percent of the time, the soybean reference price would have to be raised by 19 percent. Wheat’s would rise 5 percent, corn 3 percent. The rate for peanuts would drop 19 percent. The rate for rice would be lowered by 1 percent.

Cotton isn't included in PLC, but growers are trying to get into the program. The National Cotton Council unsuccessfully tried to get Congress to create a PLC reference price of $15.88 per hundredweight in the fiscal 2017 spending agreement. A fiscal 2018 appropriations bill pending in the Senate would set a $15 reference price for cottonseed, but even that is too high relative to other crops, according to the CRS analysts. Under the above scenario, the proposed $15 reference price would be reduced 34 percent to $9.85.

Had the $15 reference price been in place last year, the PLC payments would have represented only about 8 percent of farmers' total production costs, according to the National Cotton Council. NCC proposed a reference price for cottonseed, instead of cotton fiber, to protect the program from being challenged at the World Trade Organization. The relative impact of the cottonseed target price is difficult to compare to other commodities because while cottonseed accounts for about 25 percent of the farmers’ revenue, they need a policy that protects their overall production costs, the group says.

Rice growers don’t think their PLC reference price is high enough, In testimony before the Senate committee in July, USA Rice representative Jennifer James said the target price should "more closely reflect the significant increases in production costs for rice across all regions and take inflation into account as well.”

What about the impact of those big ARC payments that corn and soybean growers received? It turns out that the southern crops still do relatively well, even when ARC payments are taken into account.

CRS compared total USDA payments from 2014 to 2016, including ARC and crop insurance premium subsidies as well as PLC, to the average cost of production for each commodity and found that peanuts received a bigger share than another commodity: USDA payments represented 37 percent of the total cost of production for peanuts. The share of production costs for rice was 24 percent. Sorghum and wheat received 17 percent and 12 percent of their production costs covered by government payments.

Corn, meanwhile, had 10 percent of its cost of production covered by USDA payments, soybeans 5 percent.

Finally, dairy producers will find something in the report to bolster their case that the Margin Protection Program is inadequate: MPP is so small that USDA payments effectively cover none of dairy producers’ costs, according to CRS.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com