A partisan impasse on the House Agriculture Committee is making it more likely by the day that Congress won’t pass a new farm bill this year, forcing lawmakers to eventually pass a short-term extension of the 2014 law, say veterans of past farm bill battles.

An extension introduces a number of uncertainties, including a lapse in funding for expiring programs, and would allow Democrats to have more say in the shape of the next farm bill, assuming they increase their House minority in the November elections or even take control of the chamber.

House Agriculture Chairman Mike Conaway has pledged to push ahead with committee action on his draft bill next month even without Democratic support, and theoretically there is still time this year to get the legislation enacted.

But history and the calendar aren’t on Conaway’s side, especially with the committee deeply polarized over the bill’s nutrition title and Democrats believing they have a good chance of taking control of the House.

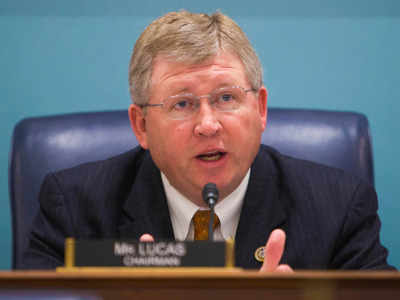

“It becomes more challenging every day” to enact a new bill, said Rep. Frank Lucas, R-Okla., Conaway’s predecessor as chairman of the committee who needed almost three years to push the 2014 farm bill to the finish line.

Rep. Frank Lucas, R-Okla., a former chair of the House Agriculture Committee

He’s not alone in thinking that. “Getting a farm bill this year after what has happened the last two weeks is going to be very difficult,” said former Texas Rep. Charlie Stenholm, who was the ranking Democrat on the committee during development of the 2002 farm bill.

“It seems that the speaker or someone in leadership has made the decision that they are going to reform the welfare system in the farm bill,” Stenholm said, referring to the expanded work requirements and tighter eligibility rules for SNAP recipients that are included in Conaway’s draft bill. House Speaker Paul Ryan has recently been pitching the farm bill as the showcase for the GOP approach to welfare reform.

Fast-track farm bills are the exception

There is precedent for waiting to move a farm bill in an election year, but the last time that happened successfully was in 1990, when George H.W. Bush was president and there were few partisan differences over the legislation.

The 1990 bill was largely an extension of the 1985 farm bill with some new twists, including the authorization of the National Organic Program. The House and Senate didn’t debate their versions of the bill until July and the bill was still signed into law before the end of November.

Every farm bill since then - with the exception of the 2014 version - was first introduced in an odd-numbered year, the first year of a new Congress, and then enacted in the first half of the following election year. The 1996 farm bill was signed into law in April, and the 2002 farm bill in May. The 2008 bill became law over a presidential veto in June of that year.

The 2014 farm bill was the first to take two Congresses to write. After the contentious "Super Committee" process in 2011, the bill was first introduced in 2012 but it stalled in the Republican House, forcing lawmakers to pass a one-year extension of the existing legislation. The bill was eventually signed into law in February 2014.

What’s unprecedented this year is the level of partisanship at the committee level. That, combined with the limited amount of time remaining for Congress to act on the legislation, is what has farm bill veterans starting to become pessimistic about the chances of passing a bill this year.

What’s unprecedented this year is the level of partisanship at the committee level. On Tuesday, Democrats decided to release their analysis of the nutrition title, even though the farm bill text has not officially been released. That, combined with the limited amount of time remaining for Congress to act on the legislation, is what has farm bill veterans starting to become pessimistic about the chances of passing a bill this year.

Both houses of Congress are in recess this week and next. After they return, the House will be in session for 13 weeks until the August recess and five more after that before the November elections. The Senate is scheduled to be in session for an additional four weeks before the elections.

That may sound like a lot of time, but farm bill veterans say that may not be enough, given the partisan battle over the House bill’s nutrition title.

Freedom Caucus poses wild card for Conaway

One of the big questions Conaway faces is whether he can get enough Republican votes to pass the bill against united Democratic opposition. Republicans currently hold a 238-192 majority with five vacancies. That means that Republicans can afford to lose fewer than 25 votes and pass the bill.

One committee Republican insists that some Democrats will ultimately support Conaway’s bill. “I think there’s some political jockeying, but I think at the end we’re going to see some bipartisan support for it,” said Rep. Ted Yoho, R-Fla.

But the Agriculture Committee’s top Democrat, Collin Peterson of Minnesota, says his colleagues are united in their opposition, and he believes Conaway could lose as many as 45 to 50 GOP votes on the floor.

Rep. Collin Peterson, D-Minn.

Peterson told Mike Adams of American Ag Radio Network on Monday that as many as 30 members of the House Freedom Caucus will vote against the bill because they don’t like farm programs, and another 15 to 20 moderate Republicans could vote no because of the changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program that are fueling the Democratic criticism. ”How you’re going to get that bill across the floor is a mystery to me,” Peterson said.

Republicans worry about Republican defections, too. As Lucas puts it, passing a partisan farm bill in the House will require support from “a number of Republicans who have never, never voted for … food security issues.”

It’s not yet clear whether the Freedom Caucus opposition will be as sizable as Peterson predicts. Yoho, who is a Freedom Caucus member, believes the SNAP reforms will appeal to his conservative colleagues. “When you deal with the Freedom Caucus there’s a lot of (practical) thinkers in there,” he said.

In response to a question from Agri-Pulse, the chairman of the Freedom Caucus, Mark Meadows, R-N.C., seemed to hint GOP conservatives could get behind a bill that reforms SNAP. He said Republicans will either have to move a conservative farm bill “where you count on the vast majority of the majority to pass it” or a bipartisan “compromise that would be more of the way we have done SNAP and other issues in the past.”

There are still some major pitfalls facing the farm bill after it passes the House. Getting floor time in the Senate is one. Democrats routinely have been forcing GOP leaders to go through the time-consuming and laborious cloture process for nominations, no matter how uncontroversial, and that limits the time for other matters. Cloture rules require up to 30 hours of debate on a nomination or bill even after cloture is invoked. Cloture motions require 60 votes for most bills and a simple majority for most nominations.

The farm bill could wind up in a queue “lined up behind three judges and four cabinet members (awaiting Senate confirmation) and watch the days roll by,” said Bill O’Conner, a former long-time GOP staff director for the House Agriculture Committee.

Assuming the Senate can pass its bill, getting agreement with the House on a final version of the farm bill may not be easy either, especially if the House GOP leadership insists on including major SNAP reforms over the objections of Senate negotiators.

Leaders of the Senate Agriculture Committee - Chairman Pat Roberts, R-Kan., and ranking member Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich.- said at the recent Agri-Pulse Ag and Food Policy Summit that the House’s SNAP reforms weren’t going anywhere in the Senate. Roberts said he and Stabenow were intent on passing a bill that would get at least 70 votes in the Senate to maximize their leverage in negotiations with the House.

Peterson said he will side with Roberts and Stabenow in the conference committee negotiations, leaving Conaway to defend the bill on his own.

Democrats seen as ‘emboldened’ to block bill

There are two additional factors that could make it less likely a farm bill passes this year: First, the budget bill enacted in February that lessened the pressure on Congress to pass a farm bill by expanding commodity program support for cotton and dairy producers; and, second, Democratic expectations that they will take control of the House this fall.

The budget agreement, which made cotton eligible for the Price Loss Coverage program and made improvements in dairy’s Margin Protection Program, “certainly makes it easier for Conaway and for some other guys to throw in the towel and say we’ll extend it (the 2014 farm bill) rather than fighting to the last ditch,” said O’Conner.

Peterson agrees. “If that hadn’t gotten done, we wouldn’t be in this position because then the chairman would need a bill,” Peterson said of the cotton and dairy provisions.

Peterson denies that House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi is requiring Democrats on the Agriculture Committee to oppose Conaway’s bill, but Peterson acknowledged that some members are motivated by optimism that they could be in the majority next year.

Lucas said the election is becoming a major factor in the timetable. “If you listened to the debates recently the other side of the room believes that they are not just speaking about the issues today, they’re speaking about their majority in the next, 116th Congress, and that’s emboldened a whole bunch of people over there,” he said. “That makes it more complicated” to pass a farm bill this year.

An extension will become politically inevitable if Congress can’t finish the bill in a post-election lame-duck session, because the 2014 farm bill kept in place permanent law, a system of price guarantees that kicks in should the bill expire without a replacement in place. Retail milk prices could potentially skyrocket under requirements in permanent law, creating what has become known as a "dairy cliff."

The 2002 farm bill was the first to be extended, and Congress also had to pass an extension of the 2008 farm bill when Congress was unable to pass a new one in 2012, according to the Congressional Research Service.

The biggest impact of an extension could be on 39 programs that have no funding after they expire Sept. 30. Peterson said an extension would leave the programs without money until a new farm bill is enacted.

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com