(Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of articles in our new Agri-Pulse series: “The seven things you should know before you write the next farm bill.” Each segment provides important background and ‘lessons learned’ that can help inform and stimulate debate before formal work starts on writing the next farm bill.)

The process for writing what was expected to be the 2012 farm bill started in a fairly routine way: staff discussions, member meetings and hearings to gather input from farmers and consumers.

Rep. Collin Peterson, D-Minn., chaired the House Agriculture Committee at the time and kicked off a series of field hearings on April 23, 2010, in Pennsylvania, listening to farmers and agribusiness leaders with a primary focus on one of his favorite topics: dairy policy.

Ranking Member Frank Lucas, R-Okla., described that hearing as “two-and-a-half hours to kick off two-and-a-half years.”

If only it had been so simple and so quick.

Sen. Blanche Lincoln, D-Ark., chaired the Senate Agriculture Committee and officially started farm bill work with a June 30, 2010, hearing in Washington, titled: “Maintaining Our Domestic Food Supply through a Strong U.S. Farm Policy.”

Just six years earlier, Lincoln had won her second Senate bid by 56 percent to 44 percent, even as Republican President George W. Bush carried her home state with 54 percent of the vote.

But by the 2010 mid-term elections, the politics in her historically “blue” state had changed rapidly. The Tea Party wave – concerned about the federal deficit and upset with President Barack Obama – was rolling across Arkansas.

Lincoln found herself trying to straddle the wave, but she needed much more than a surfboard. On one hand, she worked as a fiscally conservative centrist who could get things done, while bringing home the federal “bacon” to her farmers. She pushed back against Obama’s proposed budget cuts in farm programs, included in both his 2010 and 2011 budget proposals.

“Put simply, the president’s proposal picks winners and losers,” said Lincoln, of the president’s budget proposal, released in early 2010. It was a message that would be repeated often by her fellow southerners during the next four years.

Lincoln was the first Senate Agriculture Committee chair from Arkansas and the first woman to head the committee. But that power and significance was lost on the majority of Arkansas farmers.

Lincoln was the first Senate Agriculture Committee chair from Arkansas and the first woman to head the committee. But that power and significance was lost on the majority of Arkansas farmers.

Part of her home-state political problem was her affiliation with the president. Lincoln was one of the deciding Democratic votes to approve Obama’s signature piece of legislation, the Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare” as GOP leaders called it.

“A lot of the farmers told me that they would be fine with or without Blanche Lincoln in that seat,” a former farm organization official noted. “They just didn’t want to vote for anyone associated with Obama and Obamacare.”

In November 2010, the committee chair lost her bid for re-election to John Boozman by a whopping 58 percent to 37 percent. She was the only member of the Senate Agriculture Committee to suffer a defeat.

It was perhaps the first political signal that writing the next bill was not going to be an easy lift. But no one predicted that it would take so long – until February 2014 – and be so difficult to become law.

What was the holdup? Most of our sources interviewed for this series said there was not one single factor that made the process drag on and on and on. Instead, there was a combination of economic, fiscal, political and regional factors at play – the equivalent of a perfect storm in agricultural policy.

At the same time, they pointed to themes that can help guide those writing the next farm bill. In order to respect their requests to speak freely without retribution, we’ve not revealed some of their names.

Former staffers who worked tirelessly throughout the long hours and often sleepless nights explained the multiyear farm bill process with a simple Venn diagram that was later inscribed on their personal coffee mugs.

They “affectionately” embraced each year of the rocky process, describing the 2011 super committee process as “cluster,” the 2012 farm bill as “pencil,” the 2013 farm bill as “mind” – with each adjective hyphenated and ending with a four-letter word, starting with the letter “F.”

No shortage of drama

That’s not to say that previous farm bills – beginning with the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 – had any less drama and lacked political intrigue. After all, in the midst of the Great Depression, congressmen wanted to quickly pass a bill to “Relieve the existing National Economic Emergency by increasing agricultural purchasing power,” as they noted at the start of their legislative text.

During the depths of the Depression, farmers kept producing, but no one was buying because they had no money. Prices for cattle, hogs and many other commodities dropped dramatically. In an effort to reduce agricultural surpluses, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the AAA bill that paid farmers to cut back production – sometimes by killing and burying calves and baby pigs as part of “emergency livestock reductions.”

Since there was so little demand for pork, Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace said farmers couldn't run an “old folks home for hogs and keep them around indefinitely as pets.”

Since there was so little demand for pork, Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace said farmers couldn't run an “old folks home for hogs and keep them around indefinitely as pets.”

In Nebraska alone, the government bought about 470,000 head of cattle and 438,000 pigs. Nationwide, 6 million hogs were purchased from desperate farmers, according to the Wessels Living History Farm in York, Nebraska.

In the South, 1 million farmers were paid to plow under 10.4 million acres of cotton, which was trading at a paltry 6 cents a pound. Wheat was selling at 35 cents a bushel, corn at 15 cents and some farmers were selling hogs at 3 cents a pound.

Eventually, Wallace worked to turn those surplus agricultural products into food for hundreds of thousands of hungry U.S. citizens. He pledged that the government would purchase agricultural products “from those who have too much in order to give to those who have too little.” The AAA was amended to set up the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation (FSRC), which distributed agricultural products such as canned beef, apples, beans and pork products to relief organizations. The policy connection between food producers and hungry consumers was officially launched. It’s a give and take that serves both constituencies well.

Of course, farmers at that time were perceived as that much more important politically because they made up almost 5 percent of the relatively small U.S. population by 1935. Roosevelt could easily connect the importance of farms to the cities and built political support from both:

“If the farm population of the United States suffers and loses its purchasing power, the people in the cities in every part of the country suffer of necessity with it. One of the greatest lessons that the city dwellers have come to understand in these past two years is this: Empty pocketbooks on the farm do not turn factory wheels in the city.”

Both Roosevelt and Wallace talked passionately about the economic interdependence between farmers and consumers, but that interdependence also served them well politically. They put together the “New Deal Coalition,” an alliance of voters comprising urban Jews, Catholics and blacks, along with farmers and labor unions, in a fashion that powered the Democratic party for decades.

Fast forward to 2010

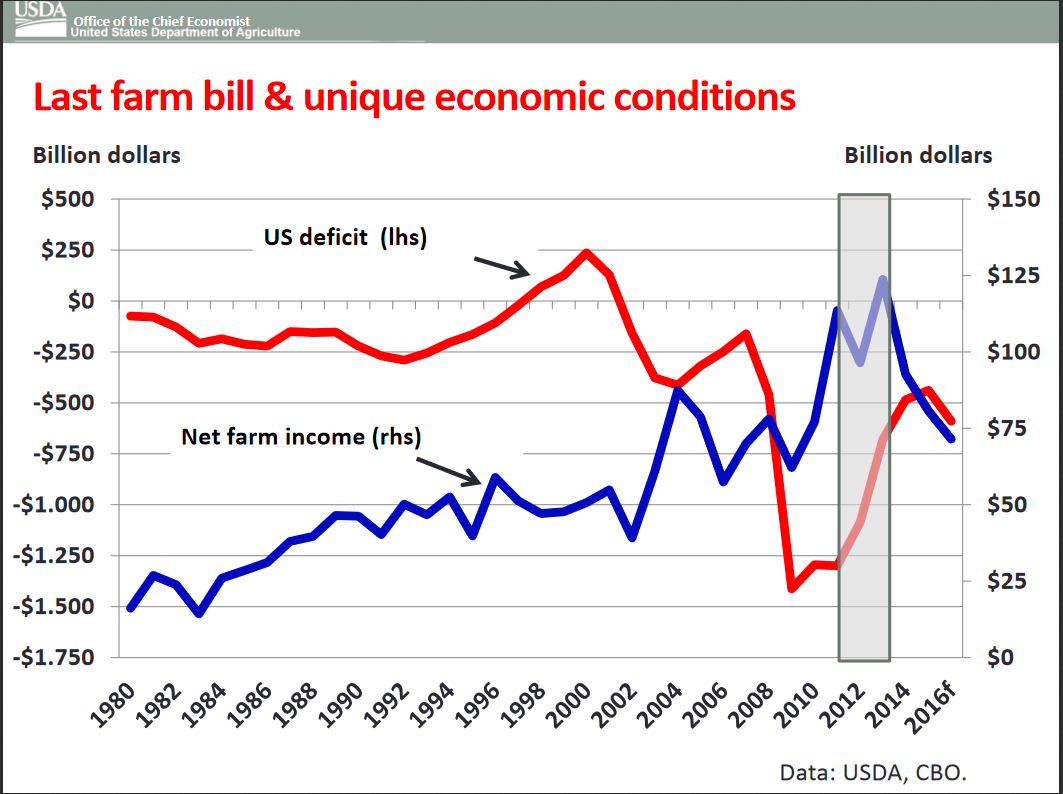

Economic conditions on the farm in 2010 were dramatically different than the 1930s or for that matter, any previous decade. And they were about to get even better.

The commodity markets were delivering like never before. Corn and soybean prices rallied to record highs – driven in part by a drought in 2012 that parched much of the nation in 2012. Fueled by the drought and herd reduction in the Southwest, cattle prices were also on the upswing, reaching $169 per hundred pounds in November 2014, the highest in history.

Farm and ranch balance sheets improved steadily from 2009 to 2014, providing an important – if not problematic – backdrop to writing the farm bill. Despite the upbeat farm economy, farmers were still receiving about $4.8 billion in fixed direct payments – regardless of what they planted.

Farm and ranch balance sheets improved steadily from 2009 to 2014, providing an important – if not problematic – backdrop to writing the farm bill. Despite the upbeat farm economy, farmers were still receiving about $4.8 billion in fixed direct payments – regardless of what they planted.

Veterans of previous farm bills understood that the farm economy is cyclical and subject to a wide variety of weather and financial risks all around the globe. And for every really positive cycle, there will be a negative one. However, it’s hard to predict how deep and how long each cycle will last.

USDA’s Economic Research Service said that the time period surrounding development of the current farm bill could be described as a “string of gains, which reflected a farm sector characterized by high crop and livestock prices, growing global demand, emerging markets for biofuels, rising incomes/net cash flows, and favorable credit market conditions.”

Net farm income peaked in 2013 at a high of $123.3 billion. By the time President Obama signed what had become the 2014 farm bill, net farm income was already headed for steep declines. Just this week, USDA’s Economic Research Service forecast net farm income for 2017 at just $62.3 billion, a little less than half the 2013 figure.

Yet, legislators were looking at their current environment. Purchases of shiny new pickup trucks and expensive high-tech tractors were trending upward. In 2010, American farmers bought almost 165,000 new tractors. By 2014, that number had topped 208,000 annually, according to data collected by the Association of Equipment Manufacturers. Overflowing pocketbooks on the farm were, indeed, turning factory wheels in the city.

From a political lens, some lawmakers said farmers were making too much money and didn’t need any more help from the government.

And many commercial farmers and ranchers weren’t terribly interested in what the government, or more specifically, the farm bill, could do for them.

“‘Just get the government out of my way and let me farm,’ or some variation, was one of the phrases we heard most often during those times,” noted a former farm organization leader. As a result, many farmers and ranchers were apathetic about writing a new five-year bill.

Shifting political landscape

Just as the farm economic landscape was rapidly changing, so was the political landscape on Capitol Hill. Sources involved in the process say they underestimated some of the ways the political dynamics – driven largely by the Tea Party – would eventually impact the next farm bill – especially compared to the 2008 farm bill.

Democrats had controlled both the House and Senate when the previous farm bill was written.

In the House, Democrats were guided by then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi. She worked closely with then-House Agriculture Committee Chairman Peterson to rally Democratic votes in support of the farm bill. And they also worked to override President George W. Bush’s veto.

Pelosi, from California, understood farm state politics better than most. As Speaker, she even attended the National Farmers Union annual meeting. She spent several hours at the opening dinner, taking time to sign autographs and dance to a rock band composed of Peterson and four other House members.

Pelosi knew she also needed the support of her farm state Democrats for other initiatives and was eager to be their champion. In a 2008 speech on the House floor, she praised the farm bill, noting that a proposed increase in food stamp funding alone was enough reason to support the measure.

“With this legislation we will help families facing high food prices,” she said.

Several Democrats, led by Rep. Ron Kind of Wisconsin and nudged along by the Environmental Working Group, wanted much bigger farm bill reforms than Pelosi was willing to accept. In a direct attack on Kind, a perennial yet unsuccessful farm bill reformer, Pelosi said that while more reform was needed, the 2008 bill made important improvements.

In with the new, out with the Blue Dogs

Barack Obama was elected president in the fall of 2008 by 69.5 million voters – a record tally for a presidential candidate. His party controlled both the House and the Senate. The political possibilities seemed endless. But that wasn’t always the case. Obama pledged comprehensive immigration reform on the campaign trail. Yet, he could not get a final bill passed through both houses. However, he was successful in getting Congress to pass his signature bill, the Affordable Care Act, in 2009.

By the 2010 elections, voters weren’t nearly so kind to the Democrats. In the Senate, the party was able to hold control with a 51 to 47 majority, along with two Independents who would likely vote with them. Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow, a Democrat, took the helm of the Agriculture Committee. Kansas Republican Sen. Pat Roberts, who had chaired the House Agriculture Committee earlier in his career, became the ranking minority member.

Although the sitting president's party usually loses congressional seats in a midterm election, the 2010 balloting resulted in the worst losses for Obama’s party in a House midterm election since 1938. Republicans won the majority with 242 members, to 193 Democrats, gaining control of the chamber for the first time since 2006.

A rancher from western Oklahoma and a self-professed farm bill historian, Rep. Frank Lucas, was tapped to head the House Agriculture Committee. Peterson became the ranking minority member.

Most noticeably missing after 2010 – at least for many in the agricultural community – were the so-called Blue Dog Democrats, especially those from the South. These members represented many agricultural and rural districts and served as swing votes on fiscally conservative issues – often siding with their GOP counterparts and against the more liberal members of their own party.

But as a result of redistricting, which placed several conservative Democrats like Charlie Stenholm of Texas and Dennis Cardoza of California in hard-to-win, largely GOP districts, the number of Blue Dogs shrank from 54 members in the 100th Congress to only 19 in the 113th.

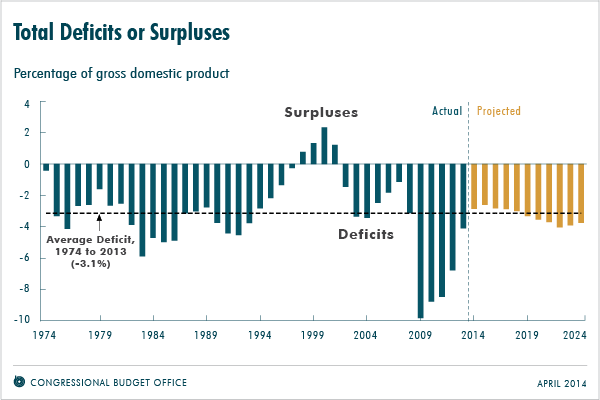

Many of these Blue Dogs were replaced by conservative Republicans who were riding on the Tea Party fervor of budget cutting and fiscal responsibility. Determined to make a difference in reducing the federal deficit and downsizing government, the massive $480 billion (over 10 years) farm bill was smack-dab in the middle of their sights. The GOP, which had picked up 63 seats in the 2010 midterm, was focused on farm bill reform. Groups like the Heritage Foundation, American Enterprise Institute and Competitive Enterprise Institute also gained considerably more energy and clout than they had enjoyed in recent years.

Ohio’s John Boehner, a former member of the House Agriculture Committee and no fan of farm bills (especially dairy price support programs) was elected Speaker. Eric Cantor, a Virginia Republican who rose up the ranks as a reformer, was elected Majority Leader and acted as somewhat of a go-between for more established GOP leaders and Tea Party members. That association would eventually put him at odds with Ag Chairman Lucas.

The relatively good news for Lucas was that he had a long-time relationship with Boehner. The Speaker respected the regular order of bills moving through the committee process. Lucas felt confident that he could work with leadership to advance a new farm bill in 2011.

Unfortunately, things didn’t work out as planned. Reform-minded lawmakers from both the left and the right started attacking the farm bill.

Trying to find the ‘new normal’

In 2011, the House and Senate Agriculture committees went about their regular business of trying to kick-start the farm bill process.

Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., who had become chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee the previous November, had to hire and organize her staff and then scheduled the first farm bill field hearing for April 9, 2011 in Lansing. But it was cancelled at the last minute due to budget negotiations that appeared to be leading to a government shutdown. The shutdown was avoided, but the farm bill hearing was postponed.

“It was another sign that the whole process was going to hell in a handbasket,” recalls one source.

The first hearing was actually held in Washington on May 26, with Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack as the key witness.

Majority staff members thought they had outlined a pretty good game plan. They knew that deficit discussions would have a big impact on whatever they did, and as the year started to unfold, there was a growing sense of urgency.

Meeting on the Michigan State University campus for the first field hearing in early June, Stabenow and ranking member Pat Roberts heard from 15 witnesses, who discussed everything from cherries to sugar beets, dairy, farm credit and research.

In August, Roberts returned home to Kansas to kick off a farm bill listening session in Wichita. All in all, there were eight Senate Ag Committee hearings.

On June 24, 2011, House Ag chair Lucas kicked off a series of 11 comprehensive “farm bill audit” hearings on Capitol Hill. With an eye on many of his new committee members – many of whom had been aligned with the Tea Party – Lucas decided to look at the farm bill from an accountant’s perspective: examining how much “bang” taxpayers and farmers were getting for their bucks.

On June 24, 2011, House Ag chair Lucas kicked off a series of 11 comprehensive “farm bill audit” hearings on Capitol Hill. With an eye on many of his new committee members – many of whom had been aligned with the Tea Party – Lucas decided to look at the farm bill from an accountant’s perspective: examining how much “bang” taxpayers and farmers were getting for their bucks.

“My goal is twofold,” Lucas said as he opened his first hearing. He wanted USDA to present a spending snapshot of all farm and food programs so members could look for duplication, examine program eligibility, and identify waste, fraud and abuse – while also looking for ways “that the department could build on success.”

In addition, Lucas wanted the audits to be educational in nature, understanding that his new members had never been through a farm bill before and represented states from Alabama to Oregon. “While our priorities may differ, our facts cannot,” Lucas warned his fellow members. “We need to prepare for the tough, and I mean tough, road ahead.” He also pledged that “every program, every title will be on the table.”

Both Lucas and Stabenow hoped for the best – some sort of normal order that would allow them to educate and consult with their committee members while writing a new farm bill that worked for taxpayers as well as those in the countryside.

Budget pressures

But inside the Beltway, all of the political oxygen was being sucked into talks about the “out of control” federal deficit, the debt ceiling and the federal budget. It seemed impossible to avoid having the farm bill drawn into the debate. And it happened again and again and again over the next few years.

The “opening salvo” arrived in January 2011, when then-Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner sent a letter to Congress urging lawmakers to act soon to increase the debt ceiling. Treasury estimated that U.S. borrowing needs could push the amount of debt past the legal borrowing limit of $14.294 trillion sometime between March 31 and May 16.

There were various attempts to find a consensus for lifting the debt ceiling, while also cutting the budget and federal spending. There was the Senate’s “Gang of Six,” a bipartisan group of three Republicans and three Democrats, who started their own discussions on a long-term deficit deal. Two members of the Senate Ag Committee, Kent Conrad, D-ND, and Saxby Chambliss, R-Ga., played key roles in those discussions.

Later on, Vice President Joe Biden got engaged in often contentious negotiations as did President Obama and top congressional leaders like Speaker Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. The verbal sparring continued for weeks.

It was these high-level discussions that really drove the four Ag Committee leaders to try and put a package together during the super committee process, according to sources close to the process.

“We kept hearing from numerous, solid sources inside leadership and the administration that the Biden discussions had $30+ billion, including direct payments on the table. The four committee leaders were damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

“They could “write a bill in secret” and eventually tick off every committee member and farm group, or they could get gored by the Super Committee, lose all capabilities to write a farm bill and possibly lose the farm program and crop insurance in the process.

“It seemed difficult to see how Stabenow, Lucas, Roberts and Peterson were supposed to win under either scenario,” the source concluded.

At each step of the way, farm bill spending was a likely target.

By the end of July, Obama announced a deal with congressional leaders. The agreement proposed a two-stage process. The first stage included $917 billion in spending cuts and other deficit reduction now, as well as a $900 billion increase in the debt ceiling.

In the second stage, a special joint congressional committee, known as the “Super Committee,” was expected to recommend further deficit reduction steps totaling $1.2 trillion or more by the end of November, with Congress obligated to vote on the proposals by the end of the year. Each congressional committee was asked to submit recommendations to achieve deficit savings from programs in their jurisdiction

If the recommendations were enacted, Obama would be authorized to increase the debt ceiling by up to $1.5 trillion – as long as the additional deficit reduction steps exceeded that amount. The president also could get the additional debt ceiling increase if both chambers of Congress passed a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution in votes to be held by the end of the year.

However, Obama would be able to request only up to $1.2 trillion in additional debt ceiling if the special congressional committee failed to agree to at least $1.2 trillion in cuts. At that point, across-the-board spending cuts – split between defense spending and nondefense programs –would be activated, equal to the difference between the committee’s recommendations and the $1.2 trillion in additional debt ceiling.

At the Michigan Agri-Business Association’s annual meeting in early 2012, Stabenow looked back to 2011, saying it was February when “we got a taste of how difficult it was going to be to pass a farm bill when the House Republicans proposed their budget, calling for a devastating $30 billion in cuts to commodities and crop insurance, $18 billion in cuts to conservation, and $127 billion in cuts to nutrition. These cuts passed the House and almost every Republican in the Senate supported them.

“Then we had negotiations between Vice President Biden and Congressman Eric Cantor that called for up to $33 billion in cuts to production agriculture.

“President Obama's budget plan also called for $33 billion in cuts to agriculture, including cuts to crop insurance – which, by the way, had already been cut.

“So that's where we were: from every direction, people have been calling for huge cuts to production agriculture at a time when agriculture is one of the few bright spots in our economy.” From that point on, there were few options: Stabenow, Roberts, Lucas and Peterson rolled up their sleeves and went to work on their “Super Committee” assignment.

“The four of us decided that, rather than having others decide what should happen regarding agriculture policy, we ought to be proposing deficit reduction cuts that make sense for agriculture,” Stabenow explained.

Sources close to those discussions told Agri-Pulse that the impact of what the Super Committee process in 2011 did in terms of shaping what became the 2014 farm bill cannot be overstated.

Stabenow had visited with ag committee members in late 2010 and early 2011 about what they wanted to see in the new farm bill. There was general agreement that, from a political standpoint, direct payments for farmers would continue in some form, according to a former staff member.

But with all of the focus on deficit reduction, it became clear before March of 2011 that direct payments would have to be eliminated entirely.

“In a really short time, they were gone.” That meant relationships with creditors – counting on those same payments for loan repayment – were also going to disappear.

“The focus on deficit reduction derailed the standard conversation,” the source added. “And it should provide a stark reminder that – for future farm bills – anything might happen under budget reconciliation.”

Another source agreed, noting: “If deficit reduction is on the table, nothing is ever safe from a farm program perspective – especially when deals are made in back rooms by a few congressional leaders without aggies in the room.”

Ultimately, the Super Committee failed to reach agreement and the ag committee leaders’ work was scrapped. Their deal, which cut $23 billion out of a measure that was anticipated to cost $480 billion over 10 years, was technically dead. Ag committee leaders noted that $23 billion was about 2 percent of the $1.2 trillion that the Super Committee was supposed to cut.

House chair Lucas and Senate chair Stabenow issued a simple statement, saying – in part:

“We are pleased we were able to work in a bipartisan way with committee members and agriculture stakeholders to generate sound ideas to cut spending by tens of billions while maintaining key priorities to grow the country’s agriculture economy. We will continue the process of reauthorizing the farm bill in the coming months, and will do so with the same bipartisan spirit that has historically defined the work of our committees.”

The Super Committee process both helped and hurt future efforts to craft a new bill, sources told Agri-Pulse.

The process allowed lawmakers to position the farm bill as something that has continually been reformed and produced savings.

In an Oct. 14, 2011, letter to the co-chairs of the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, as the “Super Committee” was officially known, Stabenow, Roberts, Lucas and Peterson wrote:

“Commodity program spending represents less than one quarter of 1 percent of the Federal Budget, and actual Commodity Title spending has been almost $25 billion below Congressional Budget Office projections at the time the 2002 and 2008 Farm Bills were passed.

“Crop insurance underwent $6 billion in reductions through the most recent renegotiation of the Standard Reinsurance Agreement, $6 billion in cuts in the last Farm Bill and $2 billion in the 2002 Farm Bill. This totals $14 billion since the passage of the Agriculture Risk Protection Act in 2000. Conservation has been cut by over $3 billion during the last five years. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) was cut by nearly $12 billion in the last Congress to offset other spending. In addition, there are also 37 programs, totaling nearly $10 billion, which expire and have no baseline into future years.

“When the 2008 farm bill was enacted, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had estimated the total cost of the farm bill at $284 billion over five years (FY2008-FY2012) and $604 billion over 10 years (FY2008-FY2017), including existing programs and changes enacted, according to the Congressional Research Service. These costs reflect mandatory outlays, not those subject to appropriations.”

But the super committee also hurt – especially in the Senate – because numerous members felt they had been cut out of the negotiations, recalled a source familiar with the process.

“It unintentionally created a trust factor that would never fully be overcome for the next 13 months,” the source told Agri-Pulse.

Post Super Committee

Over the course of just a couple of months, a new farm bill had been written in strict secrecy… and then it was scrapped. The work on the 2012 bill, became 2011 all over again – with even more unique twists to come.

The super committee process was helpful, aides said, because it laid out a lot of the program groundwork and the division of cuts. But it hurt – especially in the House – because the established parameters became points for future negotiations.

Indeed, members and advocacy groups who had been looking for even bigger changes were left unfulfilled and looked for more ways to cut.

Just a few weeks before the Super Committee recommendations were presented by the ag committee leaders, part of the Indiana congressional delegation was ready to weigh in with an even bigger farm bill cut – much to the dismay of several of their brethren.

On. Oct. 6, 2011, Dick Lugar, a former Senate Ag Committee chair, partnered with fellow Hoosier and fourth generation farmer, Rep. Marlin Stutzman, to introduce a measure that they claimed would cut the farm bill by $40 billion.

Among other things, they said the Lugar-Stutzman bill would end direct payments to farmers, counter-cyclical payments, the ACRE program and marketing assistance/loan deficiency payments.

For Stutzman, first elected in 2010, it was a chance to make his debut as a reformer. But he didn’t plan to stop there. He went on to hone his budget-cutting credentials with the Heritage Foundation and their political arm, Heritage Action. He would later champion efforts to split the “farm” from the “food” portions of the farm bill in an effort to dramatically reform both.

Farm groups scramble for alternatives

As the dust settled on the Super Committee’s colossal failure, farm organizations had already been scrambling to figure out what to offer up next.

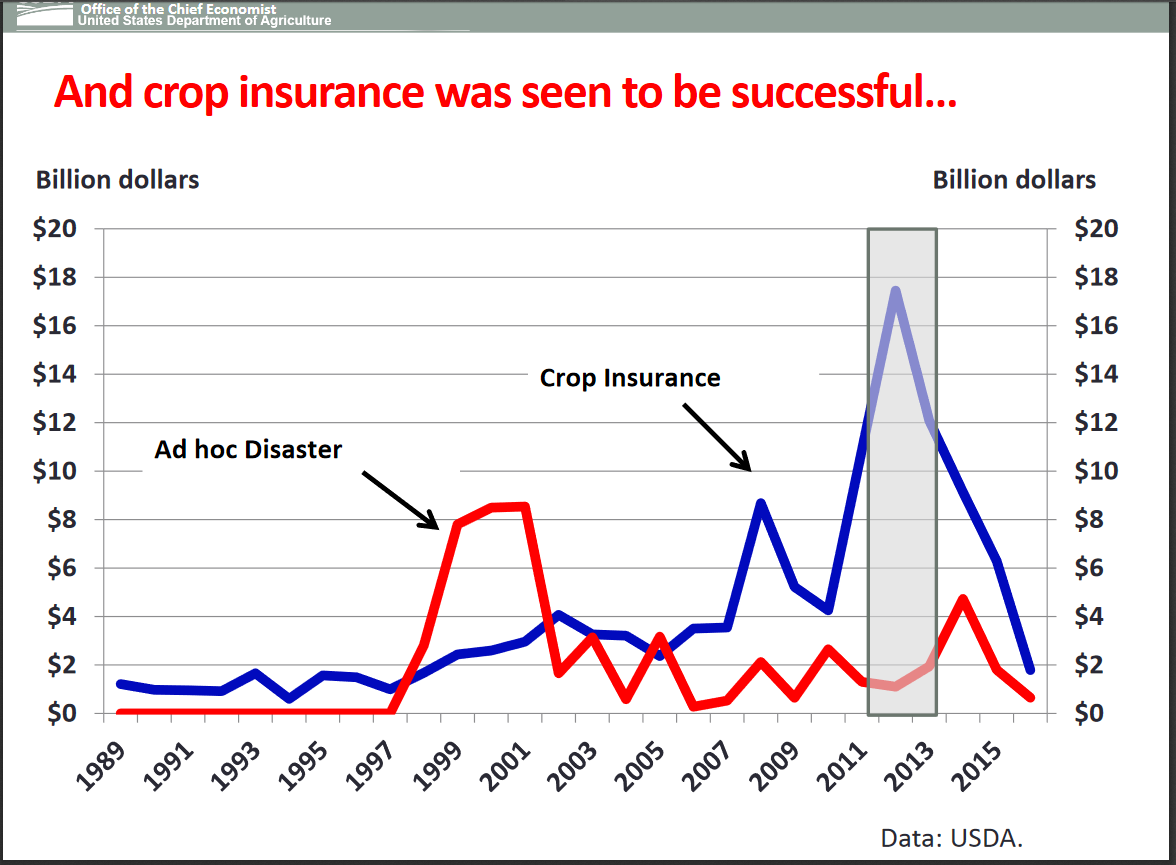

One thing they knew for sure: Direct payments, which were included in the 1996 farm bill after another period of major farm bill reform, were not going to be politically possible in the future.

Indiana Farm Bureau President Don Villwock told his colleagues that direct payments were “toast.”

But what – if any – type of program or crop insurance policy, would provide risk management in the future?

Most of the options had some form of risk management with a wide variety of long-winded and sometimes catchy names.

The National Corn Growers Association (NCGA) Corn Board liked the idea of a revenue-based risk management program and voted in December 2011 to support the “Aggregate Risk and Revenue Management” (ARRM) legislation as introduced by Sens. Sherrod Brown, John Thune, Dick Durbin and Lugar.

The American Soybean Association (ASA) originally supported “Risk Management for America’s Farmers” or RMAF, which would establish commodity-specific revenue benchmarks for individual farmers based on historical yields and prices, and compensate them for part of the difference when current-year revenue for a commodity on their farm falls below a percentage of the benchmark.

Bob Stallman, then the president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, discussed AFBF’s Systemic Risk Reduction Program (SRRP) proposal at the group’s annual meeting in January 2012, which he said would help protect farmers from catastrophic losses while recognizing current budget realities. In addition, by almost a two-to-one margin, the delegates defeated an amendment that would have allowed a patchwork of support through multiple programs for different commodities and regions.

The National Farmers Union endorsed a 2012 farm bill proposal which incorporated the use of a farmer-owned inventory system, loan rates and set-asides. They called their proposal: Market-Driven Inventory System (MDIS, pronounced Midas).

Cotton growers needed to come up with an alternative that removed them from the cross hairs of an ongoing World Trade Organization (WTO) case, brought by Brazil. The National Cotton Council endorsed a “Stacked Income Protection Plan,” dubbed STAX, which was designed to complement existing crop insurance programs.

The U.S. Rice Producers argued against a one-size fits all approach to risk management. Travis Satterfield, a Mississippi rice farmer who testified at a Senate Agriculture Committee hearing on March 15, noted, “We need a program that is financially meaningful to producers. The best way to do that is have each group craft a program that best fits their needs.”

Regional divisions emerge

Needless to say, there was no consensus. But the Senate Agriculture Committee forged on, passing a bill out of committee on April 26, 2012.

The bill, which eliminated direct payments and emphasized risk management tools and crop insurance, was set to reduce the deficit by at least $23 billion. But it failed to gain support from some Southern representatives on the committee.

Sources told Agri-Pulse that GOP Leader McConnell was very helpful behind the scenes in advancing the farm bill out of committee, but was facing strong Tea Party forces both in the Senate and at home in Kentucky. He pushed for a voice vote, but then voted “no” on a recorded vote.

After the vote, Sens. Thad Cochran, R-Miss.; Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.; Chambliss, R-Ga.; and Boozman, R-Ark., vowed to bring up amendments when the bill hit the Senate floor to further protect cotton, rice and peanuts – crops which they argued do not benefit from crop insurance.

“As we move toward a mark on the floor, I hope the issues of rice and peanuts will be given greater consideration,” Chambliss said during the markup. “If enacted under the current proposal, both peanuts and rice are going to take a huge hit.”

Stabenow assured them considerations for Southern crops were already in the bill, including the Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) for cotton, but acknowledged that more work was needed.

Stabenow assured them considerations for Southern crops were already in the bill, including the Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) for cotton, but acknowledged that more work was needed.

“It’s not about one region over another, but it is complicated,” she said. “We do have STAX for cotton, a new ag risk coverage program, special prices for rice and peanuts and new crop insurance options. I know this is not all fully developed. We realize we’re not there yet.”

Near the end of June, Stabenow and Roberts thought they had everyone on board for final passage of a bill that still had a few troublesome amendments. But they worked their magic and passed a bill out of the Senate on June 21, with a whopping 64-35 margin.

Farm organizations, however, wanted to get rid of two amendments.

One, sponsored by Sens. Durbin and Tom Coburn, R-Okla., would have applied income caps on farmers and ranchers who wished to purchase crop insurance.

The other amendment, sponsored by Sen. Chambliss of Georgia, would have required farmers purchasing crop insurance to comply with strict soil conservation erosion standards, known as cross compliance. It’s not that Chambliss was a big fan of the idea, but he wanted to signal his dissatisfaction over Sen. Roberts’ support for commodity price protections that were in the bill.

Back to the House

With action in the Senate, the House Agriculture Committee was eager to move quickly. But after a conversation with Leader Eric Cantor, Lucas decided to pause on marking up the bill the following week.

Staff said that Cantor wanted more time to assess the political situation for farm bill passage. On July 12, the Committee approved H.R. 6083, the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2012, by a vote of 35-11. The markup lasted until nearly 1 a.m.

At that time, Agri-Pulse wrote: “Chairman Frank Lucas masterfully marched through the bill, title-by-title, with Ranking Member Collin Peterson at his side, as the two moved mostly in lockstep to keep the fragile coalition they had forged focused on final approval. Lucas prodded and pulled to keep members of his caucus who sought far deeper cuts and more substantial reforms from derailing support for the bill.”

Both the House Agriculture Committee’s version and the Senate-passed bill had eliminated direct payments, but – reflecting strong regional differences – they took two different approaches on the commodity title.

The Senate version created a new shallow-loss revenue protection program that corn and soybean farmers had lobbied heavily for. The House Ag Committee’s version was different – protecting against deep losses, while also creating a countercyclical program modeled after historical target price programs that was favored by Southern growers.

Both included provisions for a new cotton program, but the House cotton package offered considerably higher levels of support with a fixed reference price in the insurance program. The House version also continued a phased-down version of direct payments for the 2014 and 2015 crops of upland cotton. Some folks were concerned about the potential impact the new provisions might have on the Brazilian cotton case.

You could almost see the relief in Lucas’ face as the bill advanced to this point. Then he waited… and waited… and waited.

Most of the crops in the countryside were burning up in a drought and members wanted to go home to campaign for the November elections. House Ag Committee members especially wanted to get back to their districts and tell everyone that they passed a farm bill. But, in a year divisible by two, Boehner and Cantor would not agree to let the bill come up for a floor vote.

The two GOP leaders claimed they didn’t have enough Republicans to vote for the bill. But Boehner and Cantor didn’t appear to be in lockstep about the strategy. In fact, often they appeared at odds.

Others wanted the delay in hopes that Republicans would win back the Senate and enable greater farm bill reforms.

Other members weighed in. Reps. Kristi Noem, R-S.D., and Peter Welch, D-Vt., spearheaded a bipartisan letter that was signed by 80 others, urging leadership to send the House Agriculture Committee’s bill to the floor for debate. GOP leaders did draft a farm bill extension bill in late July that would have trimmed direct payments and made more significant cuts in other programs, but it was later pulled for lack of support.

Speaking in Iowa after touring drought-stricken areas later that July, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack told House Republicans that they needed to quit stalling and vote on a farm bill that would include livestock disaster assistance.

Congress returned from its August recess and still, nothing was scheduled for a farm bill vote in the House. The current bill was due to expire at midnight on Sept. 30, 2012.

Farm organizations, led by AFBF’s Stallman and National Farmers Union President Roger Johnson, and including several commodity group leaders, put some additional pressure on House leadership by hosting a “Farm Bill Now!” rally on the west side of the Capitol reflecting pool.

Several members of the House and Senate Ag Committees, along with Sen. Jerry Moran, joined a few hundred lobbyists, staff and farmers on Sept. 12 to deliver a series of rallying cries about the importance of and urgent need for passing a farm bill. Farmers at home were urged to call their congressional offices. Yet, the mood in the countryside was still fairly apathetic.

“It was like the institutional interests pulling the grass roots into the fight for a new farm bill, instead of vice versa,” recalls one staff member.

Most farmers weren’t angry or motivated to push their lawmakers. And the GOP leaders on the House side weren’t budging because their caucus was splitting at the seams over the possibility of a farm bill vote.

“The silence was deafening,” a source told Agri-Pulse. “Even with the drought, we weren’t hearing from people. It was apparent that crop insurance was working as planned and that this really might be the ticket to gain support.”

Just as the rally was concluding, the Republican Study Committee was holding one of their regular press conferences, dubbed “Conversations with Conservatives.” Hosted in conjunction with the Heritage Foundation, they lunched on Chick-Fil-A and talked about things like downsizing federal government and splitting the farm bill.

Republicans Raúl Labrador of Idaho, Steve King of Iowa, Jim Jordan from Ohio, Tim Huelskamp from Kansas and Mike Mulvaney from South Carolina (now President Trump’s nominee for director of the Office of Management and Budget) were frequent participants in the news conferences.

It was another sign of how fast the politics of farm bills seemed to be changing. Sen. Moran, who formerly represented the “Big First” district and covered a wide swath of Kansas, was rallying supporters for passage while his successor, Rep. Huelskamp was trying to defeat the measure.

Sept. 30 came and went, but not without a lot of speculation about what it might mean to see a farm bill actually expire.

Two of the biggest farm bill programs – the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), more commonly known as food stamps, and federal crop insurance were not going to be impacted. SNAP had been funded through March 2013 by a recently passed Continuing Resolution, pointed out Ferd Hoefner with the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. There was no “sunset date” for crop insurance to expire. With the exception of dairy, other commodities weren’t really affected for a few more months.

But the dairy price support program itself was set to expire at the end of 2012 and revert to what’s known as “permanent law.” These provisions were included in the 1938 and 1949 farm bills and serve as a reminder that – if a new farm bill is not passed – significantly higher government price supports would kick in for most commodities.

“It would also leave out any mandatory coverage for soybeans and other oilseeds as well as peanuts and sugar,” Hoefner noted in a blog post. “In other words, it is widely considered so extremely anachronistic as to be unworkable.”

Over the next couple of months, House and Senate leaders tried to figure out a path forward on the farm bill.

In early December 2012, Lucas suggested that the bill might be able to advance as part of possible last-minute deficit reduction agreement between “the powers that be,” or President Obama and House Speaker Boehner. He talked about a transition bill that some confused with an extension of current law.

But Stabenow said she would not support an extension of the current farm bill.

“We’re not going to do an extension, we’re not going to kick the can down the road,” she said.

By December, worries about reverting to permanent law were mounting. And then the headlines started to emerge in major newspapers, warning that milk prices were about to double. Vilsack predicted the price of milk could rise to $6 per gallon, just as income taxes for almost all Americans were scheduled to increase.

Talks of extending the 2008 farm bill heat up

Both Stabenow and Lucas seemed confident that House and Senate leadership would accept their offers to extend the 2008 farm bill as part of the negotiations over the so-called “fiscal cliff,” and avoid what became known as the “dairy cliff.” They worked tirelessly over the last weeks of December to produce a farm bill extension package. But it wasn’t just a straight extension.

Some of the key principals wanted more. Stabenow wanted renewal of energy programs and organic provisions in addition to $125 million in “retroactive” insurance for tart cherry growers who had been hard hit by a spring freeze in her home state of Michigan. Lucas wanted continuation of direct payments to give growers some “certainty” on government supports for 2013. And Peterson wanted major dairy reforms from the proposed Dairy Security Act.

But as the media warned consumers of $8 per gallon milk, sources said the White House issued only one directive regarding the farm bill: Fix the looming “dairy cliff” so prices would not dramatically escalate.

As Vice President Biden and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., huddled to negotiate a package of tax provisions and budget cuts that would avoid the “fiscal cliff,” it became apparent that farm bill provisions would only be able to catch a ride if the bigger fiscal deal was reached. But it couldn’t be just any farm bill package. It had to be a deal that would be able to pass the House and Senate without causing other complications. And it needed to be something – both in substance and bill size – that didn’t overshadow a major rewrite of the nation’s tax and spending laws.

Shortly after Biden and McConnell reached a deal, Senate Majority Leader Reid told staff he wanted a “clean” farm bill extension – something that wasn’t forthcoming from the ag committee chairs. With the clock ticking down to a final vote on the larger package, McConnell’s policy adviser, Neil Chatterjee, huddled with Reid’s legislative assistant, Kasey Gillette, and Speaker Boehner’s legislative assistant, Natasha Eckard, to hammer out language for a farm bill extension. Several other House and Senate staff members contributed as they rushed to find agreement before the current bill expired on midnight Dec. 31.

It was New Year’s Eve, but lawmakers and staff had no time or energy left to celebrate.

“Everyone agreed that we could cut direct payments from a political standpoint, but because it was a 10-year ‘pay-for’ on a one-year extension, we could have easily triggered a budget point of order – threatening the larger tax and budget cutting package,” noted a source familiar with the negotiations. “And no one was willing to blow the whole fiscal cliff deal over agriculture.”

The three major staffers involved knew the dairy reform provisions were a non-starter in the House. During a GOP caucus meeting, Boehner had publicly criticized the Dairy Security Act’s market stabilization language in the farm bill extension package crafted by Lucas, Stabenow and Peterson as “Soviet style” supply management provisions. With guidance from Eckard about what could or could not pass the House, both Gillette and Chatterjee worked with numerous others to draft what they viewed as an acceptable extension of the current farm bill. Ironically, Roberts’ staff had drafted language for a straight extension weeks earlier – in order to be prepared for a multitude of possibilities.

One source described this as the “break glass in case of emergency” option.

According to sources familiar with the discussions, Stabenow was extremely upset to learn about this new version of an extension. Captured on video, she appeared to be venting her wrath on Roberts during a late-night discussion on the sidelines of the Senate floor.

She called a members-only meeting to discuss options for returning to the larger extension package. But some GOP members pointed to the potential for a budget point of order and realized that it was the condensed extension package or nothing.

After the meeting, Sen. Pat Leahy, D-Vt., argued for an adjustment in the Milk Income Loss Contract (MILC) provisions, and Reid signaled that Leahy would have to quickly come up with his own offset that was acceptable to Democrats because Republicans were done with the deal. Ultimately, funding for SNAP was reduced to pay for enhanced assistance to dairy farmers.

Fast forward a few weeks into 2013 and Reid endorsed a new fiscal package that appeared to contain much of the farm bill extension package that had been advanced by Stabenow and rejected in late December – leading some to speculate that Stabenow, who is a tireless farm bill negotiator, finally got her “payback” from Reid.

Although the sequester option had not yet been formally introduced, an outline of the measure indicated that Reid’s bill would cut defense spending and net farm bill spending each by $27.5 billion over the coming decade and postpone cuts called for in the sequester until Jan. 2, 2014. It would also raise an additional $55 billion by placing a minimum tax on millionaires and closing other tax loopholes.

Stabenow told reporters that the $27.5 billion represented a ceiling on savings going forward, and the Agriculture Committee would not be required to make additional cuts when members wrote a new five-year farm bill.

The total elimination of direct payments would save about $31 billion, but the bill would “reinvest” $3.5 billion to pay for 24 of the 37 farm bill programs that expired earlier than all other farm bill programs. The early expiration date was a budget gimmick, designed to make those programs fit into funding parameters available at the time the 2008 farm bill was written.

Ultimately, the Senate rejected rival proposals to stop the sequester, ensuring the $85 billion in automatic spending cuts began March 1, 2013.

Now, it was time to get back to work on the farm bill, but there was a new player leading Republicans in the Senate Agriculture Committee and one fewer on the House Agriculture Committee.

Southern influence

Unable to stay on as ranking member of the powerful Appropriations Committee, Sen. Thad Cochran, R-Miss., asserted his seniority over Sen. Roberts and was selected to take over as ranking GOP member of the agriculture committee. Roberts told Agri-Pulse that Cochran “has his full support” and that “seniority is a well-respected and historic privilege in the U.S. Senate.” Cochran had previously served as committee chairman from 2003 to 2005.

But his return meant that Southern grower groups would have even more influence on the next bill, much to the dismay of Midwestern interests and Roberts.

“My message to Kansas farmers and ranchers is that I will continue to be your voice and your champion at every turn,” Roberts emphasized.

Farm bill veterans knew from previous experience that they should never underestimate the influence of Southerners in policymaking. The commodity title was soon to become “Southern fried” to improve its flavor for cotton, rice and peanut growers.

Just a few days earlier, another Kansan was in the farm policy headlines. Tim Huelskamp had been kicked off the House Agriculture Committee after repeated run-ins with Boehner. A Tea Party favorite, Huelskamp was a frequent critic of the farm bill’s nutrition title and also of the speaker and Majority Leader Eric Cantor.

Huelskamp had voted against the House Ag Committee’s farm bill proposal, saying it spent too much on food stamps and offered little regulatory relief for farmers. It was the first time in nearly 100 years that someone from his state had not served on the committee.

The long, hot summer of 2013

The push was on to finally move farm bills during the summer of 2013 and produce a final product before the one-year extension expired in September.

The Senate Ag Committee passed its bill on May 13, 15-5, with Roberts, Thune, and Nebraska Republican Mike Johanns voting against the measure in protest of commodity title revisions that had been modified to win support from Southern rice and peanut growers. The regional fault lines among the GOP members were growing deeper.

New York Democrat Kristen Gillibrand also opposed the measure over cuts to nutrition funding.

Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky was the sole Southern GOP senator to oppose the measure.

Just two days later, the House Agriculture Committee passed a new five-year farm bill by a 36-10 margin. The bill was largely similar to the bill passed through the committee the year before by a 35-11 margin, with larger cuts in the nutrition title and minor changes in farm safety net programs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) gave the draft a preliminary score of $39.7 billion in savings over 10 years, which included $6.4 billion in cuts already required by budget sequestration. Direct spending authorized by the draft legislation would total $940 billion over 10 years.

The Senate’s farm bill debate opened just five days later.

“It’s a jobs bill… it’s a trade bill… it’s a reform bill… it’s a conservation bill… and it’s a kitchen table bill,” said Stabenow at the start of the debate. The White House pledged to support the measure but asked for more savings in the crop insurance program before Obama could sign it.

The first amendment offered, by Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and John McCain, R-Ariz., aimed to eliminate taxpayer-subsidized crop insurance for tobacco production. But more attempts to cut crop insurance – capping subsidies for the wealthiest producers and capping premium support – were on the way. The Senate approved its five-year farm bill (S. 954) on June 10 with a strong bipartisan 66-27 vote, ending the two-week debate and moving the focus to the House floor.

“We’ve done our part again,” Stabenow said in what seemed like a familiar refrain. “We’ve worked closely together. …We’ll get this done.” Ranking member Cochran also applauded passage of the bill, which he said “reflects fiscal responsibility but provides a workable and strong safety net for families and producers of food and fiber that we hope they never need.”

Roberts said he was concerned that the measure was “a return to trade and market-distorting policies of the past, does not represent reforms achieved in last year’s Senate-passed bill and does not cut enough wasteful spending.”

“I do not believe this is a reform bill,” he continued. “I believe it is a rear-view mirror bill. Target prices under any name – whether counter-cyclical payments, adverse market payments or government subsidies – are proven to be trade- and market- distorting.”

The commodity title now included the price-based Adverse Market Program (AMP), which set target prices at a percentage of recent average prices and provided that support levels be updated annually.

House horrors

Back on the House side, GOP leaders finally seemed ready to give Lucas his wish – a vote for his farm bill on the House floor in late June. But emotions and influence-peddling were running on overtime. GOP leaders thought they might have the votes, but the whip count was uncertain.

Groups like Heritage Action pushed hard to split the “farm” portion of the bill from its “food” portion and were tracking the action for their “key vote” scorecard.

Heritage Action Fund was also using a round of radio ads to attack three Republicans and a Democrat in agriculture-heavy districts over the farm bill. The advertisements, complete with the sound of squealing pigs in the background, targeted Lucas; Republicans Rick Crawford of Arkansas and Martha Roby of Alabama; and North Carolina’s Mike McIntyre, one of the remaining “Blue Dog” Democrats. Heritage accused McIntyre of trying to push a “food-stamp bill” through Congress.

The members, the ads said, were “putting a tuxedo on a pig” by backing the bill.

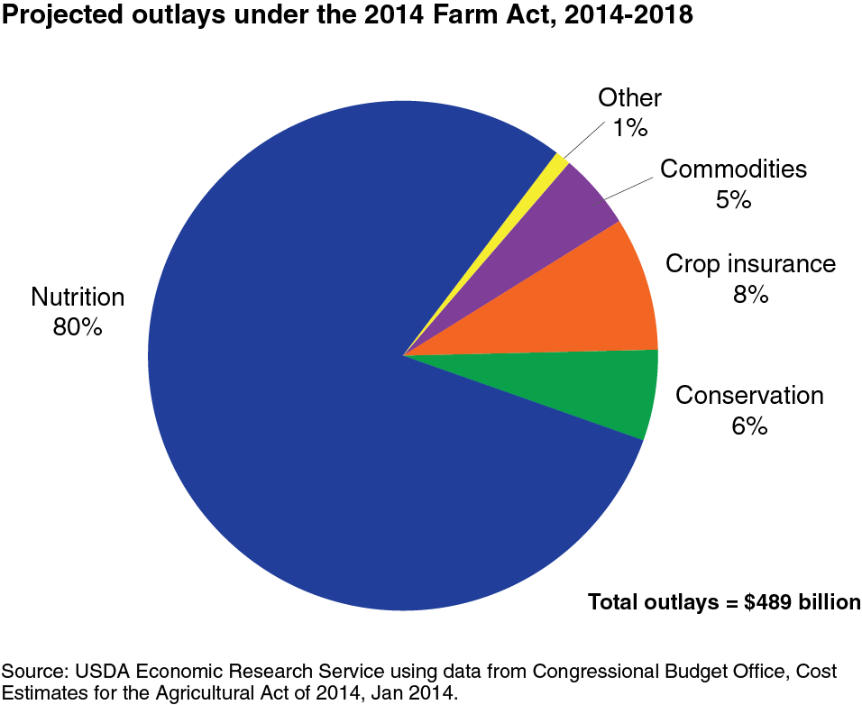

Support for splitting the bill was mixed, even in farm country. Farmers would take one look at a chart showing that the nutrition programs consumed about 80 percent of farm bill spending and assumed that they would be better off passing a much lower cost “farm only” bill.

Support for splitting the bill was mixed, even in farm country. Farmers would take one look at a chart showing that the nutrition programs consumed about 80 percent of farm bill spending and assumed that they would be better off passing a much lower cost “farm only” bill.

What they failed to look at was a map of House congressional districts, showing that only 34 were truly dependent on farming. – not nearly enough to support the 218 votes needed to pass a farm bill on the House floor. The political “math” required the farm and food portions to pass together.

House floor action on the farm bill started June 19.

According to Rep. Steve King, R-Iowa, Ag Chairman Lucas acted like a “maestro” in trying to orchestrate a new farm bill over two days with dozens of opportunities for amendments. But the Oklahoma Republican could not persuade enough lawmakers to play the same tune. In the end, 234 representatives voted “no,” including 62 from his own party.

Shortly before the measure failed by a 195-234 vote, Lucas made a final plea for passage, urging the House to vote “yes” and avoid the label of “a dysfunctional body … full of dysfunctional people.” But hopes for bipartisanship were largely dashed, with only 24 Democrats voting for the bill.

Lucas won support from top GOP leaders, including Boehner; Majority Leader Cantor, R-Va.; and Whip Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif.

However, the bill – which would have cut food stamps by $20.5 billion over the next 10 years –

just didn’t cut enough out of farm and nutrition programs for lawmakers aligned with the Tea Party, including Huelskamp and Stutzman, as well as Michele Bachmann, R-Minn.; Paul Broun, R-Ga.; and Steve Stockman, R-Texas.

They all voted “no” on final passage, which meant these “reformers” basically got nothing in terms of reforms. Without passage of a new farm bill, there would be zero cuts in food stamps, and direct payments would continue.

So what would it take to persuade those 62 Republican lawmakers to vote for passage of the farm bill? In some cases, the perfect seemed to be the enemy of the good.

Prior to the final votes, Huelskamp told Agri-Pulse he might vote for the farm bill if the House approved his one amendment to require SNAP beneficiaries to work and to cut the program by an additional $10 billion. His amendment was defeated, 175-250, with 57 Republicans voting “no.”

A separate amendment by Rep. Steve Southerland, R-Fla., seemed to be the deal-breaker for Democrats.

Much to the dismay of the Lucas team, Leader Cantor personally spoke on the House floor in favor of Southerland’s amendment, which would have allowed states to require that SNAP recipients seek work. It passed, 227-198. It was like dropping a poison pill in an already toxic political environment.

After the farm bill went down to defeat, both Republicans and Democrats took turns blaming the other party.

“It's a demonstration of major amateur hour,” noted Ranking Democrat Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., about the House leadership after the vote. “They didn't get the results and they put the blame on someone else.”

Pelosi noted that 58 GOP members voted for Southerland's amendment, but then they voted “no” on the final bill.

“Why would you put an amendment there that would lose Democratic votes, that is going to make the bill worse?” she asked. “And they didn’t stick with leadership on final passage. Isn't that remarkable?”

Cantor tried to put the blame back on Pelosi.

“I'm extremely disappointed that Nancy Pelosi and Democratic leadership have at the last minute chosen to derail years of bipartisan work on the farm bill and related reforms. This bill was far from perfect, but the only way to achieve meaningful reform, such as Congressman Southerland’s amendment reforming the food stamp program, was in conference,” Cantor said.

Peterson, who now serves as ranking member of the House Committee on Agriculture, said he originally had over 40 Democrats willing to vote for the farm bill. But after the amendment passed to remove the dairy stabilization provisions, he lost three to four members, and about a dozen more switched their votes after the Southerland amendment.

“It was a combination of dairy and Southerland,” Peterson said of the two amendments that prompted Democrats to reject the final bill.

When Southerland’s food stamp provision came up as the last amendment, “I had a bunch of people come up to me and say, ‘I was with you, but this is it. I'm done,’ ” Peterson added.

Some Republicans blamed Peterson for overpromising and under-delivering his fellow Democrats to support the bill. But the Minnesota Democrat, who led passage of the 2008 farm bill when Democrats controlled the House, was quick to respond.

“I'm not in charge. They are.”

Conservatives celebrate

Shortly after the House defeated the farm bill on June 20, 2013, Rep. Justin Amash, along with hundreds of business leaders, government officials and staff, attended a $250-a-plate dinner hosted by the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). The libertarian group, which espouses “free market” principles, made a James Bond spoof video called “Capitalism Never Dies,” and the group’s president, Lawson Bader, sported a kilt in tribute to actor Sean Connery.

But before the elaborate Bond-themed dinner began, the master of ceremonies announced two other reasons to celebrate: CEI had just raised $1 million from sources like Google, Facebook, Koch, Altria and the Association of American Railroads. Plus, there was the political victory: the organization had helped defeat the farm bill – thanks in part to Amash and dozens of other House conservatives.

CEI aligned with conservative groups, such as Heritage Action, Taxpayers for Common Sense and the National Taxpayers Union, along with an eclectic mix of other organizations, including the National Black Farmers Association, U.S. PIRG, Defenders of Wildlife and the Environmental Working Group, in order to bring down the farm bill. Several of them expressed concerns about the largesse of the bill, which was expected to cost about $956 billion over the next 10 years, at a time when farmers were enjoying record incomes. The largest portion – almost 80 percent – would be spent on food stamps.

It was widely known that Amash had concerns about SNAP and supported splitting the nutrition and farm portion of the bill, while adding more work requirements for SNAP recipients. But he also opposed price supports and other farm programs “because they damage the economy, harm consumers, and hurt the environment by encouraging more agricultural production than may be necessary,” he explained on his Facebook page.

Asked after the CEI dinner what it would take to win his support for the farm bill, Amash echoed concerns from many conservatives. He wanted to see big cuts in SNAP, but also in crop insurance.

Farm only farm bill

Leader Cantor embraced the conservatives’ position and split the farm bill into two parts, with the nutrition and food stamp provisions as separate packages.

On July 10, the American Farm Bureau Federation board voted unanimously to reaffirm its opposition to the proposal. But it was a tough, emotional vote for many and they understood that they would be bucking the GOP leadership. Within minutes after the vote, delegates from Texas and Alabama signaled to their congressional delegations that they were ready to flip their position.

The AFBF opposition came a day after the National Farmers Union’s board of directors voted unanimously against splitting the bill. They both joined 530 other organizations on a letter opposed to splitting the bill.

On July 11, Cantor and his fellow conservatives were successful. The debate was particularly brutal, but in a 216-208 vote, Republicans pushed through a scaled-down farm bill which mirrored much of the farm provisions that had failed to pass the House in June. But the measure also included a repeal of the so called “permanent law.”

For the first time since 1973, food stamps were not part of the farm bill.

“We wanted separation, and we got it,” said Stutzman.

Lucas called passage of the legislation “a huge step forward,” as the House did indeed pass a farm bill.

During floor debate, Lucas appealed to his colleagues: “In the nature of making this place work, pass the ‘farm’ farm bill so I can begin to work on the nutrition part of the farm bill next.”

On Sept. 19, the House passed the nutrition portion of the former farm bill, cutting nearly $40 billion out of the food stamp program over the next decade. Shaped largely be Cantor, H.R. 3102, the Nutrition Reform and Work Opportunity Act of 2013, passed by a vote of 217-210.

The bill was strongly opposed by House Democrats and some Republicans who charged it would increase hunger by ending benefits for nearly 4 million people in 2014.

After the vote, Vilsack said the bill “stands no chance of becoming law” and the White House threatened a veto.

Path toward conference

The path forward was littered with potholes, but Lucas finally had another chance to craft a new farm bill. Within days, Boehner said he would appoint conferees.

Senate leaders appointed farm bill conferees on Aug. 1, 2013. House leaders didn’t name conferees until Oct 12.

But staff members had already been preparing and figuring out how to work through many of differences between the House and Senate versions. Consensus on the conservation title was relatively easy because there had been strong agreement from both sides during the debate. But as 2013 was winding down, there were still several key areas where consensus was elusive.

1. Planted vs. base. After artfully guiding the passage of two farm bills through the Senate, Stabenow had also grown increasingly skeptical of the commodity title provisions that Lucas insisted on including: linking high target prices to planted acres, rather than base acres.

It was an ideological argument that bridged party lines and geographies. Stabenow was supported by Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus, D-Mont., Johanns of Nebraska, and others because of fears that such language could have real-world trade implications.

For Stabenow, another World Trade Organization (WTO) challenge could ultimately threaten the auto industry in places like her home state of Michigan. Yet, Lucas and Cochran, supported by Chambliss and other Southern senators, were in lockstep on most of Title One and saw no reason to change course.

2. Disagreements on the definition of “actively engaged” and payment limits were also creating big regional tensions that lasted until almost the very end of the conference. Midwestern Senators, such as Iowa’s Charles Grassley, wanted to tighten farm program payment limits and reduce the number of non-farmers who could receive payments. Southerners, including Sen. Cochran and Chairman Lucas disagreed.

Both the House and Senate measures included payment caps on certain programs, as Carl Zulauf and Gary Schnitkey pointed out in a FarmDocdaily report on farm bill conference issues.

“Payments are denied to entities with an aggregate gross income (AGI) over 3 years that exceeds $750,000 in the Senate bill and $950,000 in the House bill. Differences exist between the two bills in the programs to which the AGI limit applies, with the House bill applying the limit to a broader range of programs, including conservation programs. Last, the Senate bill, but not the House bill, contains a provision that redefines active involvement in farming.”

3. SNAP. With the Senate cutting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program by $4 billion over 10 years and the House slashing almost $40 billion, the two sides started poles apart. Some GOP members believed that the “sweet spot” to pass both chambers would be to cut $10 billion over 10 years, rolling back $1 billion per year in savings, with Southerland’s amendment on work requirements converted to a pilot program.

But others said that a double-digit number would still be too much for Stabenow to move through the Senate, especially if the cuts were achieved by trimming categorical eligibility or by embracing all of Southerland’s work requirements. Sources close to the negotiations said that if the cuts were achieved mainly by shutting down SNAP eligibility linked to the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) program, known as “heat and eat,” it would be more acceptable in the Senate. But some of those same sources differed on how much savings would actually be achieved through LIHEAP reform, with estimates ranging from $8.7-$12 billion.

Another concern: How to get GOP conservatives, who passed a stand-alone nutrition title with almost $40 billion in cuts, to vote for something in the $8-$10 billion range? You don’t. That meant Rep. Peterson would have to make sure plenty of his fellow Democrats were on board. But if the SNAP compromise cut too deep, they would bail, too.

4. Dairy. Normally, the dairy title is one of the last deals to be negotiated. But if the Senate version prevailed in conference, Boehner might once again be reluctant to bring the farm bill to the House floor. Boehner had consistently opposed the dairy stabilization provisions which, along with the Dairy Security Act, were advanced by the National Milk Producers Federation. Instead, Boehner backed the Goodlatte-Scott amendment, which removed what he and many milk processors viewed as “supply management.”

However, the Dairy Security Act had long been one of Peterson’s top priorities. If Peterson didn’t sign off on the conference committee agreement, there could be even fewer Democrats willing to vote for final passage.

Earlier in the fall, Ohio State economists John Newton and Cameron Thraen suggested a re-tooled dairy farm safety net that some said would be a potential compromise between the House and Senate dairy reforms because it did not require a market supply program. And it scored under $1 billion. Dubbed MILC Insurance, the economists proposed increasing eligibility of MILC up to 4 million pounds per year and allow farms an option to choose annually between: 1) MILC participation, or 2) a stand-alone margin insurance program as their elected safety net, with margin insurance from $4 to $6.50 per hundredweight.

Staff members were going back and forth with the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to score various options that might lead to a compromise.

Throughout this time, the four principals also had to keep in mind how to win at least 218 votes in the House, 60 votes in the Senate and President Obama’s signature.

President Obama consistently called on Congress to pass a new farm bill. But other than his budget proposals, he had offered few specifics about what should or should not be in the final package. But in late November as the conferees were deliberating, the White House offered a new report, making a strong defense for continuation of SNAP as “one of the main anchors of the social safety net . . . and providing economic benefits to communities.”

Like what you see here? Agri-Pulse subscribers get our Daily Harvest email and Daybreak audio Monday through Friday mornings, a 16-page newsletter on Wednesdays, and access to premium content on our ag and rural policy website. Sign up for your four-week free trial Agri-Pulse subscription.

The report also offered sharp criticism of the SNAP cuts included in the House version of the farm bill, noting that: “According to CBO estimates, the House bill would mean approximately 3.8 million low-income people in 2014 – and an average of nearly 3 million people each year over the coming decade – would lose SNAP benefits, among other damaging changes.”

The White House had been somewhat supportive of the smaller Senate cuts. But in releasing the report, White House National Economic Advisor Gene Sperling seemed to raise a red veto flag on any compromise that exceeded the Senate’s $4 billion level, calling the House farm bill, with almost $40 billion in SNAP cuts, “harsh and unacceptable.”

Still, the conferees worked away to whittle down the differences. On Dec. 4, Stabenow and Cochran sat down with Lucas and Peterson and came out of the meeting together smiling. They said they discussed every title of the bill and narrowed many differences.

Reporters started to compare the meetings with the secrecy surrounding the naming of a new Pope in the Vatican. Every day, they’d joke about a cloud of white smoke signaling that an agreement had finally been reached. But the waiting continued.

By Jan. 10, 2014, rumors were flying that a deal had finally been agreed to. Both Stabenow and Lucas seemed a bit dour on a day that many stakeholders and lawmakers thought might be “the day” for a deal announcement.

“There’s no white smoke yet,” Stabenow said. “It’s a big, complicated bill.” Lucas said it was “highly unlikely” that conferees would announce a framework for a bill that week. “There are still lots of conversations.”

At a press conference later that day, Boehner took another swipe at the proposed dairy policy, which involved a margin insurance program with a mix of supply management tools. That approach, which had been pushed hard by Peterson, aimed to help limit over-production while keeping insurance costs down.

In strong opposition, Boehner and many House members argued the approach would lead to unfair market intervention and higher milk prices. Boehner said dairy producers should have access to margin insurance, but without production limits.

“I fought off supply management for 23 years and Peterson knows that won’t change,” Boehner said. “I’m confident that the conference report will not include supply management provisions for the dairy program.”

Rep. Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., and Rep. David Scott, D-Ga., who had authored a successful amendment that would remove production limits in the House farm bill, sent a letter to top farm bill conferees.

“More than 140 diverse groups have joined with 291 House Members, including 95 Democrats, in voicing their opposition to supply management,” Goodlatte wrote. “As the conferees continue their work, I urge them to remember the House vote and adopt the House-passed Goodlatte-Scott amendment as part of the final farm bill.”

Jim Mulhern, president and chief executive officer of the National Milk Producers Federation, wanted conferees to support a safety net for dairy farmers that combined a margin insurance program with a market stabilization mechanism.

“It’s unfortunate that misguided opposition to this program still lingers in some quarters,” Mulhern said “The dairy title’s market stabilization is a standby component that may never be triggered but is needed to protect dairy farmers should markets collapse again as they did in 2008-09. It is a small matter in the overall scheme of this bill.”

Logjam breaks

On Jan. 24, 2014, the four principals announced a bipartisan agreement on a five-year farm bill that among other things would eliminate direct payments, revise commodity supports (calculated on base acres), enhance crop insurance, and streamline conservation programs. Everyone had given some and taken some. And leadership in both the House and Senate appeared to be on board.

Boehner called the agreement “a positive step in the right direction…..While I hoped many of these reforms would go further, the status quo is simply unacceptable,” Boehner said. “This legislation, however, is worthy of the House’s support.”

The “Agricultural Act of 2014” passed in the House on Jan. 29, 251-166, and in the Senate on Feb. 4 by 68-32 margin. Obama and Stabenow flew to her alma mater on Feb. 7 for a bill signing ceremony on the campus of Michigan State University.

The “Agricultural Act of 2014” passed in the House on Jan. 29, 251-166, and in the Senate on Feb. 4 by 68-32 margin. Obama and Stabenow flew to her alma mater on Feb. 7 for a bill signing ceremony on the campus of Michigan State University.

Just a few weeks ago, in a meeting with new members of the House Agriculture Committee, Lucas tried to put the 2014 farm bill into perspective compared to previous farm bills.

“They’ve all been so different,” he emphasized. From his perspective, farm bills have evolved over three distinctly different generations, adapting to reflect different parts of U.S. agricultural history and economic conditions.

The very first farm bill, in 1933, was about supply management because we had stockpiles of excess commodities, Lucas told Agri-Pulse. Subsequent farm bills were used to build upon the tools first used at that time. The second generation of farm bills, launched in 1996, was dubbed “Freedom to Farm” as a way to move farmers away from production controls and target prices. That’s when direct or “transition” payments were first launched and Roberts chaired the House Agriculture Committee.

The third generation of farm bills – culminating in the 2014 bill – was focused on getting rid of direct payments, Lucas said.

“When you have to reinvent the wheel, like we did, it’s tough,” Lucas said of the last farm bill experience. “But like 2002 and 2008, when you are refining existing policy, it’s much easier.”

Lucas predicts that the next farm bill will be a refinement process, rather than a reinvention process.

“I just hope that (current House Agriculture Chairman Mike) Conaway doesn’t have to go through what Pat (Roberts) did in 1996 or I did in 2012, 2013 and 2014.”

#30