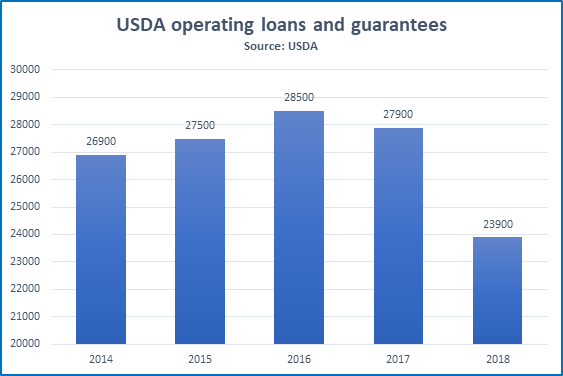

With agricultural markets adrift and the U.S. farm economy fraying in recent years, a groundswell of farmers heading for USDA's Farm Service Agency, the last-resort lender for operating loans and guarantees, might be expected.

Instead, the number of FSA direct operating loans slipped 16 percent from 2016 to 2018 while operating loan guarantees plunged 27 percent.

The decline “isn’t what we anticipated,” said William Cobb, acting deputy administrator of FSA Farm Loan Programs.

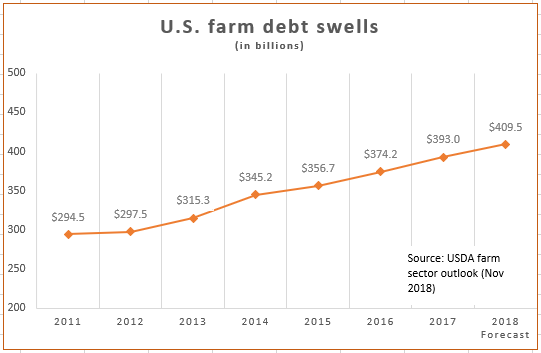

After all, American farmers’ inflation-adjusted net farm income is projected to fall 14 percent this year, and their total debt has swollen to $410 billion, up nearly 40 percent since 2011, USDA said in its recent 2018 farm sector economic outlook.

In fact, in commenting on that report, USDA Chief Economist Rob Johansson declared “10 percent of crop farms and 6.2 percent of livestock farms are forecast to be highly or very highly leveraged.”

So why the slump in demand for USDA’s distressed-borrower operating loans?

A part of the answer is cautious use of credit, Cobb suggests. “Credit has been tighter, (and) with the poor economic conditions . . . people are more reserved and kind of stick with what’s essential, rather than what they’d like to do.”

At the same time, the profile of FSA’s loan portfolio remains surprisingly strong, despite deepening farm debt and sour farm economic outlook. Its number of delinquent loans, as of Sept. 30 of each year and across all FSA loans, has crept up a modest 1 percentage point, to 11.8 percent, since 2015. Meanwhile, in the same years, the dollar amount of delinquent loans has shrunk by about $400 million. The overall delinquency rate for the FAS operating loans portfolio, the first category to show stress in hard times, is higher and has risen 2 percentage points in four years, to 15.6 percent.

But those moderate delinquency levels are “something we’re very pleased with,” Cobb says.

Note, too, that despite the downturn in operating loans, overall approvals of new loans at FSA offices has remained very steady. In recent years, they’ve approved about 70 percent of all loan applications – in fact, approvals ticked up to 72 percent in the year ending Sept. 30.

FSA has continued to target a growing share of loans to beginning farmers (those in the first 10 years of farming): In FY 2018, 19,700 loans, or 57 percent of total loans, were made to beginning farmers. Cobb says the share has risen from only around 30 percent a decade ago.

What’s more, while FSA’s operating credit business has shrunk, farm borrowers have been lining up for FSA’s direct farm ownership loans (mortgages). The annual volume has set records five years in a row, hitting $1.1 billion in 2018.

In fact, Jeff Gruetzmacher, senior vice president of Royal Bank in Lancaster, Wis., said the recent increases in farm real estate debt are actually an important reason for the drop in demand for farm operating loans with banks, FSA and other lenders.

Gruetzmacher serves a diversified farming region of cropping, dairy and other livestock in southwest Wisconsin. Dairy farmers there, especially, have been financially throttled by weak markets. In recent years, “as the cash flows became tighter, people have reassessed their operations,” he says, “and bankers have looked at how to restructure their debt, taking advantage of the low interest rates for longer-term loans and moving some debt onto (farm) real estate.”

For many stressed farms, “I think that process has already happened . . . (and) that is why you see a decrease in guaranteed operating loans,” Gruetzmacher says. He points out that farmland values, which soared for years and have recently remained stable, if not rising a little, in his region, have been crucial in making such restructuring possible.

“My opinion is that most bankers, including us, have been helping their customers through that (restructuring) . . . and what needed to be done was done,” he said.

Jeffrey Swanhorst, chief executive of AgriBank, describes a similar trend among farm credit cooperatives. AgriBank serves a district with 14 farm credit co-ops across 15 north-central states, and Swanhorst says, “to some extent, there has been a re-balancing of the debt load.”

Farming was very profitable for several years after the 2008 recession, and farmers were paying cash for pricey equipment, even for land, or paying off short-term loans straight out of working capital, he said.

So, in the past few years, “farmers have taken . . . some of that debt, where they’ve borrowed short term, and put it on a long-term loan against farm real estate . . . in order to provide longer payment terms and get a decent amount of working capital.”

Cobb, meanwhile, notes that FSA doesn’t refinance its farm ownership loans the way private lenders may do, but he sees two types of increasingly popular FSA ownership loans – both targeted to beginning farmers – as enticing new borrowers. One is the “down payment loan,” which requires a 5 percent down payment and is financed up to 45 percent by FSA and 50 percent by a private lender. It features a 1.5 percent rate (versus 4.25 percent for other FSA farmland loans). The other is the “participation loan,” financed 50-50 by FSA and private lenders and offering a 2.5 percent rate.

Cobb, meanwhile, notes that FSA doesn’t refinance its farm ownership loans the way private lenders may do, but he sees two types of increasingly popular FSA ownership loans – both targeted to beginning farmers – as enticing new borrowers. One is the “down payment loan,” which requires a 5 percent down payment and is financed up to 45 percent by FSA and 50 percent by a private lender. It features a 1.5 percent rate (versus 4.25 percent for other FSA farmland loans). The other is the “participation loan,” financed 50-50 by FSA and private lenders and offering a 2.5 percent rate.

Cobb says 58 percent of FSA ownership loans in 2018 were in those two program. He said the rise in ownership loans overall “is probably (because) those two programs are popular, and may become more popular as interest rates increase.”

Meanwhile, Mark Scanlan, senior vice president of the Independent Community Bankers of America, says ICBA’s agricultural bankers have echoed Gruetzmacher’s observation about operating farm debt being moved to land mortgages.

However, Scanlan says ag bankers with whom he’s visited point to “a combination of factors,” headed by “deteriorating farm conditions,” behind the ebb in operating loans with FSA and private lenders, “depending on what area of the country you’re talking about and specific situations.” Those factors:

- “With declining farm income . . . and greater financial stress, an obvious consequence is that not as many (farm borrowers) are going to be able to cash flow . . . so it’s not going to be worthwhile doing all the paperwork required to submit the application.”

- “People thinking of getting into farming may (be opting) to delay it a year or two” until markets improve. So, “there are fewer young farmers (asking for loans), and the ones remaining are getting bigger, and they have bigger financing needs (than FSA can accommodate).”

- Some bankers “have been working with borrowers to allow them to have carryover debt,” and that means fewer new seasonal loans.

- For FSA in particular, “the loan limit has been too small,” constraining the field of potential applicants. However, he notes the 2018 farm bill now before Congress would increase the maximums – hiking the annual total in credit per farm from $1.4 million to $1.75 million.

- Also, he notes, “some farmers have had excellent crops in recent years,” easing the need for borrowing.

Swanhorst notes, however, that many co-ops in his region have, instead, seen demand for operating loans jump. They serve members who grow grain and oilseeds, and robust production and hampered export markets have forced them to store their harvests rather them sell their crops. That spells a need for new operating credit, he points out.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com