Nearly one in every two American farmers would be interested in being paid to help reduce climate change, even though the climate issue is a relatively low priority and producers aren’t necessarily worried about its impact on their operations, according to the latest Agri-Pulse poll of U.S. producers.

Interest in carbon markets crosses party lines and is especially strong among younger farmers, according to the Aimpoint Research survey of 600 farmers and ranchers nationwide. The poll, conducted between Feb. 19 and March 13, also found that large majorities of farmers already have undertaken many practices that conserve carbon in the soil, reduce the use of pesticides and other inputs, or curb runoff of pollutants that can foul streams and lakes.

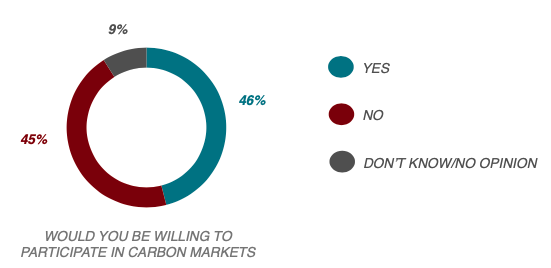

Some 46% of those polled answered “yes,” when asked whether they would be willing to “participate in carbon markets, where you are paid to implement certain practices on your farm in exchange for reducing greenhouse gases.” Forty-five percent said they would not participate in carbon markets. The remaining said they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Age makes a difference: Some 54% the farmers under the age of 45 said they would take part in carbon markets, compared to 38% of those over 65 and 50% of those between ages 55 and 64.

Some 43% of parties who identify as Republican or who lean Republican said they would participate in carbon markets, compared to 54% of Democrats and 49% of independents.

Efforts to create national carbon credit trading foundered a decade ago when the Obama administration was unable to persuade Congress to establish a cap-and-trade system that would have forced polluters to slash greenhouse gas emissions or to buy credits that would have been generated by farmers and other sectors.

But private efforts to develop carbon markets have been gathering momentum recently because of commitments made by corporations to voluntarily reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Bruce Knight, a former undersecretary for USDA’s conservation programs in the George W. Bush administration, said he is seeing a generational change in attitudes toward climate issue and carbon markets.

There is “genuine interest among farmers in this, especially under the age of 50. There is a generational change in attitude,” he said.

He also said “the last 10 years worth of weather makes it difficult to deny that something is going on” in the climate.

Knight operates a consulting firm and is helping develop the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, a national effort to develop a nationwide credit trading system for farm practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve water quality.

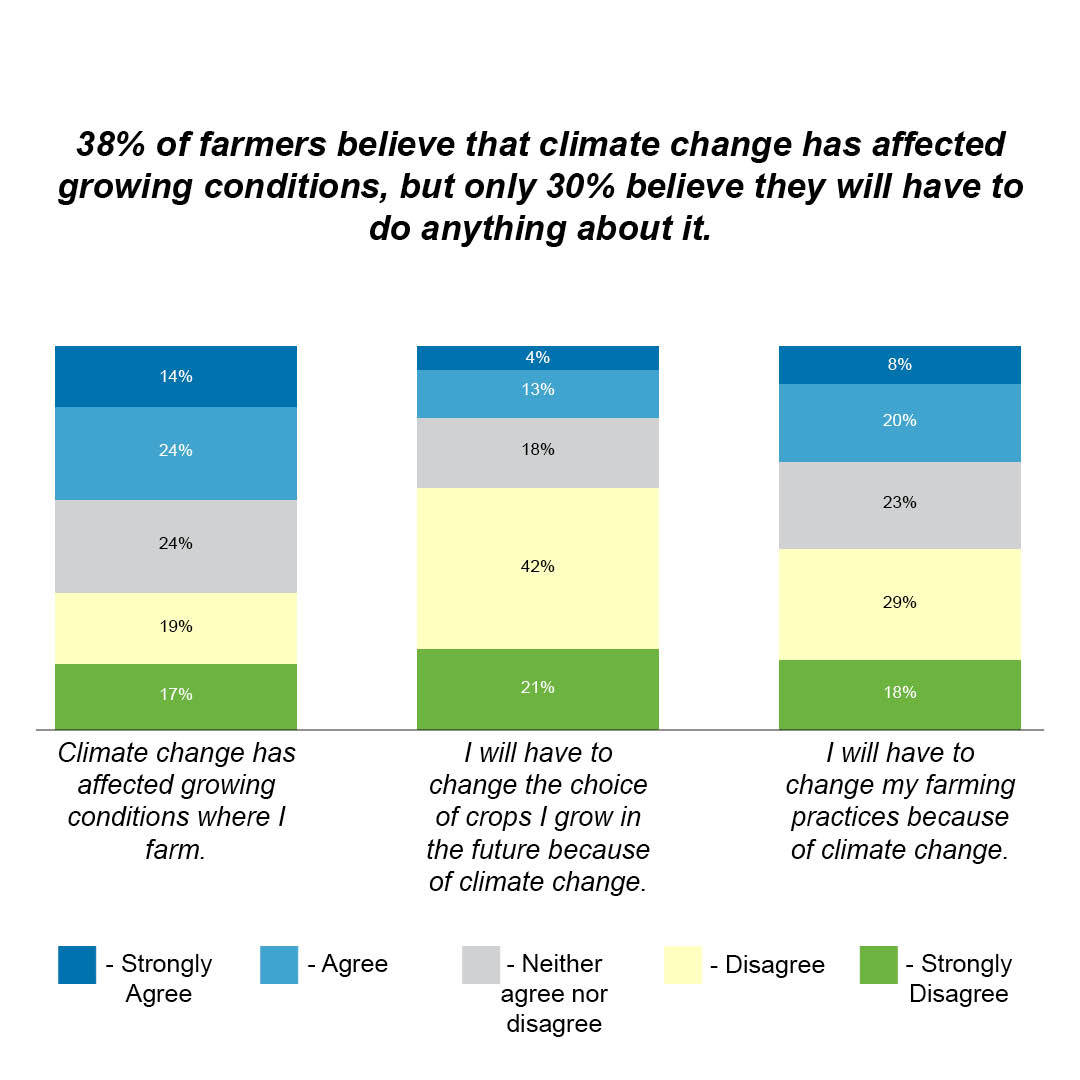

Climate change isn’t a pressing issue for the vast majority of farmers, though more than 40% of older farmers believe that growing conditions on their farms have been altered by climate change.

The farmers were asked to rate the importance to them of twelve issues on a scale of one to 10; the issues included facilitating U.S. agricultural exports, protecting against terrorism, reducing the federal deficit, repairing U.S. infrastructure, stopping illegal immigration and protecting gun rights as well as addressing climate change.

Climate change came in dead last in priority with an average score of 5.01, a small increase of 4.89 since the fall of 2018. The top issue for farmers this year was selling more U.S. farm products overseas, with a score of 8.85.

There was a sharp partisan divide on the climate issue: Some 62% of Democratic or Democratic-leaning farmers ranked the issue between 8 to 10, compared to 13% of GOP farmers and 29% of independents.

Roger Johnson, the recently retired president of the National Farmers Union and a former Democratic agriculture commissioner in North Dakota, said terms matter when it comes to the issue.

Farmers have often been more willing to call themselves conservationists than environmentalists and they tend to associate the term” climate change” with environmentalism and carbon markets with conservation. “We farmers, and most others as well, prefer the latter” term, he said in an email after reviewing the poll results.

“I’ve long felt the key is to get the incentives lined up so farmers are compensated for doing what we as society want done,” he said. “So I’m not surprised by the results. Leaders should accept the science and work to provide incentives.”

A telling age divide emerged on the question of whether farmers are being personally affected by climate change. Older producers were more likely than younger to say that it had affected growing conditions where they farm

Overall, 38% of farmers overall and 45% of producers between from ages 55 to 64 said their farm had been affected by climate change, compared to 27% of farmers under 44 years of age.

Some 41% of farmers over 65 said they had been affected climate change as well as 31 percent of farmers between ages 45 and 54.

But only a fraction of farmers overall believe they will have to change their choice of crops or alter their farming practices to deal with climate change, which scientists say will result in some regions being drier and hotter and others being wetter and warmer than they are now.

Some 28% of the farmers polled said they would probably have to change farming practices because of climate change and only 14% said crop choices would have to be altered.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

That’s probably because farmers believe that improvements in crop traits will make it possible for them to keep growing the same mix of commodities they do now, said Knight, a former lobbyist for the National Corn Growers Association.

New corn varieties have already been made more drought tolerant through both conventional breeding techniques as well as genetic engineering.

“You may change what you select for the traits of the corn or soybeans, but you probably don’t change the planting decisions because of climate anytime in the near future,” Knight said.

Moreover, farmers already are switching to no-till farming and other resource-conserving practices, according to the poll, which tracks with data reported elsewhere:

- 77% said they had implemented new conservation practices.

- 73% said they were using no-till.

- 65% have invested in precision agriculture techniques that allow nutrients and pesticides to be applied according to need.

- 64% have reduced energy use.

- 60% are applying fewer pesticides.

- 48% have cut back on fertilizer usage.

- 45% have reduced water usage.

The remaining Democratic presidential candidates, former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, are both pledging to make climate change a major priority of their respective potential administrations. The front-running Biden promises to "ensure our agricultural sector is the first in the world to achieve net-zero emissions, and that our farmers earn income as we meet this milestone." Among other things, he would put more money into the Conservation Stewardship Program that pays farmers for soil and water-conserving practices.

Meanwhile, the Agriculture Department under President Donald Trump's administration in February proposed cutting agriculture's environmental footprint in half by 2050, and Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue suggested carbon markets could encourage farmers to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. If reducing carbon emissions "is a social goal and social priority there, then let’s put a price over carbon emissions, and I think you can really see farmers show out in their carbon sequestration efforts," Perdue told reporters.

Debbie Reed, executive director of the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, says getting more farmers interested in addressing climate change will require showing producers how they can help address the problem rather than blaming them for it. “Finger-pointing is not helpful, not warranted, and just plain wrongheaded,” she said.

But she thinks that the growing interest of corporations in reducing the carbon intensity of their supply chain already is trickling down to farms.

“When companies first started looking at their own footprints and taking actions, it largely did not touch or require engagement or discussions with ag sector. It was mostly internal and not related” to the farmer, she said.

But then when companies started to look at their indirect footprints (that process and what brought them there is a longer conversation … and food and beverage companies had to look at ag, there was this dawning realization that ag has a pretty big footprint that largely had not been addressed.”

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.