USDA’s massive Farmers to Families food box program kicked off May 15 with people lining up to get fresh produce, meat and dairy products. But questions lingered about the efficiency of the program and why USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service gave contracts to some companies that appeared unqualified to fulfill them.

USDA awarded $1.2 billion to nearly 200 companies around the country to procure, assemble and deliver boxes to food banks and other nonprofits. Boxes can include fresh fruits and vegetables, dairy products, precooked meat, a combination of items, and fluid milk.

In Vermont, so many people showed up at the Vermont Food Bank’s distribution point at the Berlin airport that by 2 p.m., some had to be turned away. At one point, there were four-and-a-half miles of cars lined up.

Traffic management became an issue, and portable toilets had to be set up. “We’ve never seen anything like it,” Vermont Food Bank spokesperson Nicole Whalen said.

People liked their USDA boxes, but demand was so high that after 1,000 of the USDA boxes were distributed, the food bank had to resort to giving people FEMA Meals-Ready-to-Eat (MREs), which she described as containing “much less compelling things.”

In El Paso, Texas, the situation was similar. “I’ve never seen five, six, seven miles of cars to get food,” said Rene Campos, operations manager for food box contract-winner Segovia’s Distributing, which is putting together fruit and vegetable boxes.

Campos said the company should have no problem fulfilling its contract. “As far as meeting the agricultural needs, it shouldn’t be a problem,” he said, “unless there’s an act of God.”

And Tom Stenzel, president and CEO of the United Fresh Produce Association, said from what he’s heard from members, “the rollout went pretty well. People are making it happen.”

Stenzel acknowledged “a couple of surprises in the early days with the contracts that went to some people who didn’t seem as prepared as what we had expected, but I do have confidence USDA is going to provide proper audit and oversight.”

In a May 11 letter to AMS Administrator Bruce Summers, Stenzel said, “We know of several upstanding companies that are current government contractors to USDA and the DOD Fresh program who were seemingly denied on mistaken grounds” and posed a series of questions about the program.

“They were rushing so fast and we were all pushing them,” Stenzel said. “They can only believe what was put on an application. I think they’re going to be very aware of the need to double-check.”

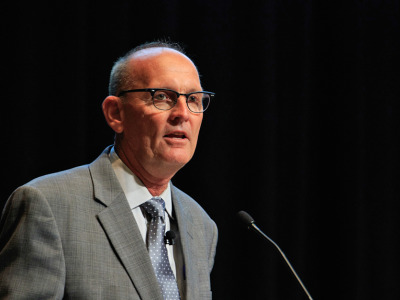

USDA Undersecretary Greg Ibach

On a conference call Tuesday with reporters, Greg Ibach, USDA's Undersecretary for Marketing and Regulatory Programs, said some of the awarded contractors “have very great abilities that you wouldn’t necessarily be able to assess by looking at the name of the organization.”

“We feel confident that between our screening process and our audit process that we will be able to assure that those companies will be successful in fulfilling the responsibilities and the design of our program,” Ibach said.

Soon after the contracts were awarded, AMS was greeted with articles from Bloomberg, Politico and the San Antonio Express-News raising questions about some of the awardees, most notably CRE8AD8 (pronounced like “create a date”), a wedding and event planning company in San Antonio that won $39.1 million, one of the biggest contracts in the country, without seeming to possess relevant experience, or a Perishable Agricultural Commodities (PACA) license — a prerequisite for doing business in the produce world.

CRE8AD8’s contract includes about $13 million for fruits and vegetables and dairy products and another $25.8 million for a precooked meat box containing pork and chicken.

CREA8AD8 CEO Gregorio Palomino did not respond to email and phone messages, but he told the Express-News he was applying for a PACA license. As of Tuesday, there was no record on AMS’s ePACA website of CRE8AD8.

He has been faced with wholesalers refusing to work with him, the newspaper reported May 18.

“I understand the sentiment from others that may have lost the bid, but I can’t imagine turning away work or an opportunity to generate revenue for their business,” Palomino told the newspaper. “We want to buy from local growers and purveyors, and help get San Antonio residents back to work, safely.”

Brent Erenwert, CEO of Brothers Produce in Houston, has been the most vocal about his displeasure with the way contracts were awarded. He called it a “travesty” that CRE8AD8 received a contract.

“There are not enough answers” about how contracts were awarded, he said. “Did computers spin these out, did a bingo machine, we don’t know.”

“We’ve got something called a PACA license that protects us in case somebody doesn’t pay us,” he said. “That should have been the first box that was checked in this whole program.”

USDA initially said PACA licenses were required, but an AMS spokesperson now says applicants for the food box program “must have, or acquire, a PACA license to comply with the contractual requirement.”

“To be in the produce industry, you have to be PACA-licensed,” Campos says.

Eric Cooper, president and CEO of the San Antonio Food Bank, says he has been working with Palomino on a strategy for distributing the boxes, which CRE8AD8 plans to begin doing June 1.

But it’s the lack of a national plan that he says has he and other food banks concerned about the potential for food waste.

The program gives a lot of leeway to the distributors to determine where food goes. In its FAQ for the program, AMS says it “will not offer guidance on what nonprofit organizations to supply,” which Cooper says has led to confusion about who is distributing food to whom.

“There’s no coordination of the nonprofits,” Cooper says.

The distributors he’s getting food from have all delivered food to the food bank’s warehouse, as opposed to distribution points, which is not how he reads the requirements in the Request for Proposal.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

In addition, Cooper says that in a teleconference with other Feeding America food banks around the country, he heard stories of food going to nonprofits who didn’t need it, forcing them to call food banks for pickup and causing Cooper to worry that the program could result in food waste.

“I think there could be a more strategic plan and I hope USDA learns from the first round,” he said. The next round of distribution begins July 1 and runs through the end of August. USDA has the option of extending contracts beyond the initial base period of May 15-June 30 for three additional, two-month "option periods."

Both Cooper and the Vermont Food Bank’s Whalen mentioned the SNAP program as an avenue for food delivery. Cooper also brought up the already existing Emergency Food Assistance Program and other food assistance programs with which USDA already has experience.

“There’s plenty of proven strategies that just need funding behind them,” he says.

Under SNAP, people “can use an EBT card on their timeline to get food they can use instead of just getting a box,” Whalen said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.