Harold Dueck sees cover crops as a necessity in his cotton fields to protect the fragile cotton seedlings from the harsh and unpredictable west Texas winds. But in the dry climate of Gaines County, he's often forced to tap precious underground water supplies to keep the cover crops alive.

It’s a system that Dueck has been using for 15 years, and one many growers in the region use if they have access to underground water. The practice of seeding cotton into a cover crop each spring ultimately improves cotton production, he said.

“It's very beneficial in the long run because you can up your yield significantly,” Dueck said.

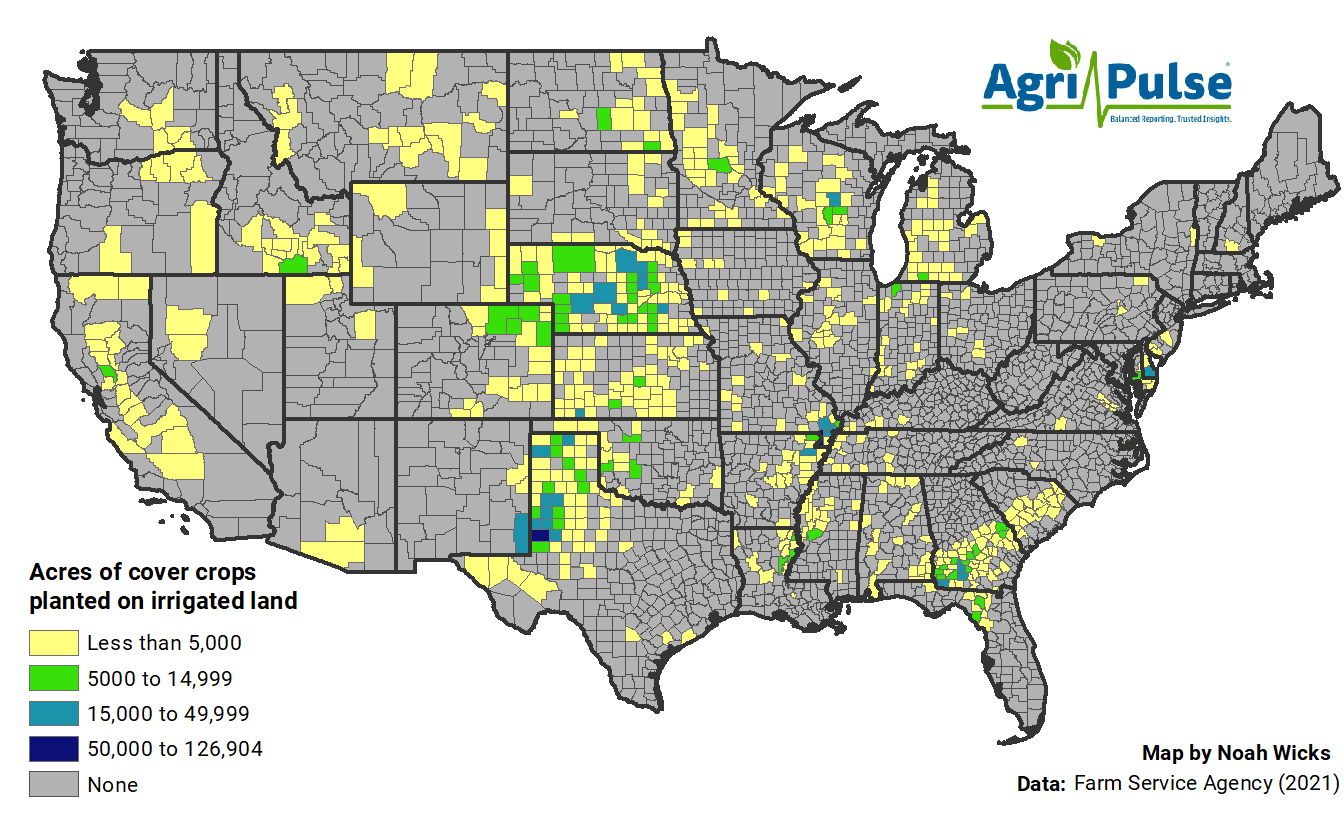

Gaines County, the seventh-largest cotton-producing county in the U.S., contained over 120,000 acres of cover crops on irrigated acres last year — the most of any county in the nation. Nationwide, farmers reported planting cover crops on 1.9 million acres of irrigated U.S. land to the Farm Service Agency in 2021.

Cover crops qualified for a $5-an-acre crop insurance premium subsidy in 2021 and will be eligible again in 2022. There is no restriction for planting on irrigated land. President Joe Biden's Build Back Better bill, currently stalled in the Senate, would authorize payments of up to $25 an acre to farmers who plant cover crops.

While planting cover crops on irrigated land doesn’t necessarily mean the cover crops themselves will be irrigated, some cover crop irrigation likely happens in arid and semi-arid regions. Establishing cover crops requires water and in these areas, it often doesn’t make sense for producers to plant without access to water sources.

“We are so limited with rainfall, we have to irrigate here for it to be beneficial,” Dueck said. “If you don't irrigate, you may never even get your cover crop up.”

Dunklin County, Missouri, had the second most cover crop acres planted on irrigated land, with 111,000 acres reported to the FSA in 2021. Between 21,000 and 43,000 acres of cover crops were planted on irrigated land in Dawson, Lamb, Hale, and Yoakum Counties in Texas and Stoddard and New Madrid Counties in Missouri.

Johnny Hunter, a farmer in Stoddard County, began planting cover crops in 2013 after dealing with poor water infiltration and irrigation efficiency during the 2012 drought. He doesn’t actually irrigate his cover crops, and his cash crops now require less irrigation because the soil is capturing more water than it previously did, he said.

“Keeping the ground covered with either a living cover crop or the residue after you terminate, it holds that moisture a lot longer on the surface of the soil,” Hunter said. “Once you do irrigate, it's more meaningful.”

Adding cover crops to already irrigated cropping systems can lead to better infiltration and a reduction in the amount of water producers need to use, according to Rob Myers, the national liaison on cover crops and soil health for the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program and the director of the University of Missouri’s Center for Regenerative Agriculture.

Myers said cover crops can help stimulate earthworm activity under the soil, which creates tunnels that allow the water to quickly soak in. Additionally, the cover crop roots create holes in the soil that also contribute to increased infiltration.

“All these factors together lead to a better water situation in the soil for the cash crop and as a result, we don't need as much irrigation water,” Myers said.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

Julie and Shawn Holladay, who grow cotton next door to Gaines County in Dawson County, Texas, say they’ve seen the benefits of cover crops through water infiltration. They also noticed that their yields have increased since they started planting cover crops 10 years ago.

“We're probably up 15% on our yields with using the same amount of water,” said Julie Holladay. The cover crop lowers the temperature of the soil, she said.

On the central and western Plains, depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer, the region's main underground water source, is a chronic concern for farmers.

Rick Kellison, project director for the Texas Alliance for Water Conservation, has told Agri-Pulse it’s premature to know how much impact a $25-per-acre payment would have on Ogallala water demand. But he said a significant increase in irrigated cover crops could pose a challenge for water availability.

Shawn Holladay said he believes that irrigating cover crops is worth the water it takes because of the many benefits they provide, including reduced nitrogen leaching.

The value of irrigating the cover crops themselves, however, largely depends on the farm, its location and the availability of water.

A Michigan State University article estimated that applying one or two half-inch applications of water in Michigan and Indiana often costs under $5 per acre. Naveen Adusumilli, an associate professor of agricultural economics at Louisiana State University, says that cost is around $4 to $7 per acre in Louisiana. The cost of pumping water could be higher in Western states, which can range from $48 to $68 per acre, according to the USDA.

Adusumilli, the LSU economics professor, said irrigating cover crops isn’t worth the cost for most water-strapped producers unless they were planning on using those cover crops for livestock feed.

“If they have it just to protect the soil moisture, it wouldn't make any economic sense for them to give a lot of irrigation to it,” Adusumilli said. “Because you're actually trying to keep the moisture in the ground, so why do you want to spend another $4 or $5 an acre each to put water to that cover crop?”

For both his cover crops and his cotton, Dueck said he pays around $150 to $200 for irrigation in a normal year, including the costs of monitoring and maintaining his irrigation system.

Dueck said the price varies based on the amount of water the crops need. On average, he said he uses around four to six inches of water to establish his cover crops, but on years with plenty of rainfall, he may not need to use any.

He also said the benefits to his cotton yield help to make those costs worth it.

“If we had the sand blowing on a year-to-year basis, it would deplete our soil of its nutrients and also stunt the growth of our seedling,” he said. “Through all of that, we would have a significant yield decrease across the board.”

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.