A contingent of Republicans from the prairie pothole region want to prohibit federal agencies from entering into permanent conservation easement agreements with landowners, putting an expiration date on contracts that otherwise would last forever.

Sens. Mike Rounds, R-S.D., and Kevin Cramer, R-N.D., and Reps. Michelle Fischbach, R-Minn., and Kelly Armstrong, R-N.D., introduced bills this year to end perpetual contracts with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Landowners voluntarily sign these agreements — which stipulate how they are allowed to use the land in the future — and, in exchange, the agency provides monetary compensation.

But once a property holder signs a permanent easement agreement, they’re locked into that contract forever. And federal agencies, Rounds says, aren’t required to be a “good neighbor” once easements are in place. If disputes arise over unclear language, farmers are often stuck following the agency’s interpretation, he says.

“It just seems to me that when you make a permanent easement, that binds multiple generations into the future to negotiating or being subject to the whims of whichever administration in Washington D.C. happens to be in power,” Rounds told Agri-Pulse. “I like the idea of termed leases or easements, where the federal government has to be a good neighbor or they may not be invited back in for another term.”

Rounds introduced the NRCS Wetland Compliance and Appeals Reform Act last month. The bill, co-sponsored by Cramer and Sen. John Hoeven, R-N.D., would only allow the agency to enter into termed agreements.

Earlier this year, Cramer proposed another bill that would prohibit the U.S. Fish and Wildlife from entering into easements with a term of more than 50 years. Fischbach and Armstrong sponsored companion legislation in the House.

The bills are supported by several farm groups in Minnesota and the Dakotas that have raised concerns about the limitations permanent easements place on future farmers and the role agencies play in interpreting the language of the agreements. But the proposals are likely to ruffle feathers in the conservation and hunting communities since permanent easements also provide long-term protection of waterfowl-supporting wetlands and other ecosystems important to species in the region.

Sen. Mike Rounds, R-S.D.

Sen. Mike Rounds, R-S.D.

“There are a number of landowners who have decided that permanent easements work really well for their operations and their families, and I don't know why we would take that option away from them,” said John Devney, the chief policy officer for Delta Waterfowl.

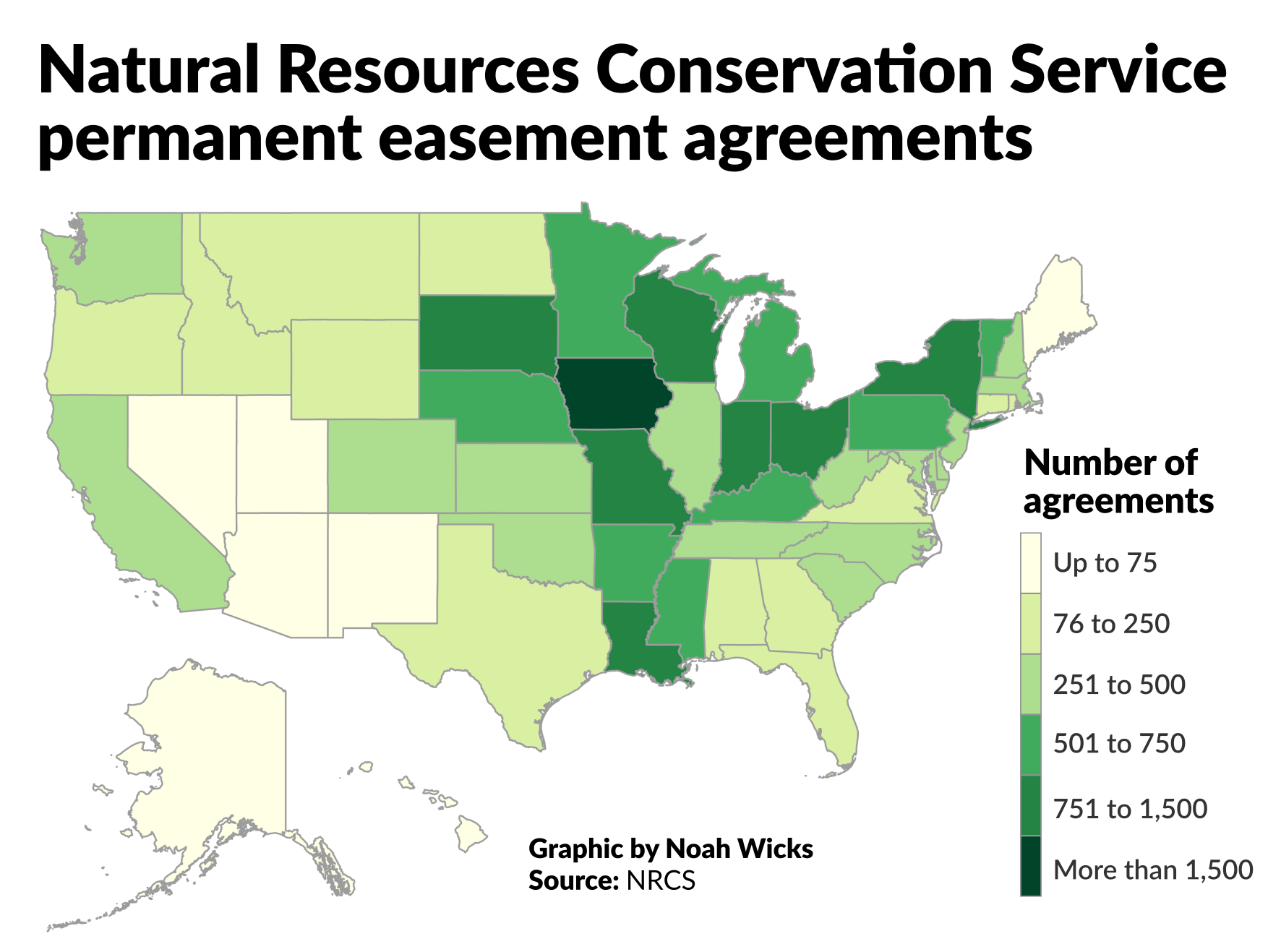

Permanent easements are a popular contract option, at least with NRCS. The agency is currently locked into 21,000 permanent agreements with landowners, approximately 87% of all the easement contracts the agency has signed.

More than half of these easements — or 10,859, to be exact — are part of the agency’s Wetlands Reserve Program, which targets wetland restoration. Another 4,323 were signed through the Farm and Ranch Lands protection program, which prevents landowners from using agricultural land for nonagricultural purposes. The remaining contracts were implemented through 10 other NRCS-run programs.

The Fish and Wildlife service, on the other hand, has signed a total of 37,677 permanent easement agreements with landowners. These easements cover over 4 million acres of land, according to statistics from the agency.

Julia Peebles, the manager of agriculture and sustainability at Ducks Unlimited, says permanent easements are popular for a reason. They’re voluntary, incentive-based and allow landowners to retain ownership of their property and define how they believe later generations should use the land.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse!

“It’s their choice if they want to enroll in a conservation easement,” Peebles told Agri-Pulse. “It allows them to keep and maintain their operations … or any natural resources or historical resources they have. It’s also great for, I think, society as a whole. It’s great for scenic views, it’s great for recreational access, it’s great for soil health, clean water.”

But farm groups throughout the Western Corn Belt, including the South Dakota Farm Bureau, the North Dakota Farm Bureau and the South Dakota Farmers Union, feel permanent easement contracts place undue constraints on future generations of farmers.

But farm groups throughout the Western Corn Belt, including the South Dakota Farm Bureau, the North Dakota Farm Bureau and the South Dakota Farmers Union, feel permanent easement contracts place undue constraints on future generations of farmers.

“Permanent is a long time, and we have the thought that it’s not fair to tie the hands of future generations,” South Dakota Farm Bureau President Scott VanderWal told Agri-Pulse.

Concerns about agency relations with landowners have also fueled opposition to permanent easements. North Dakota farmers, in particular, have objected to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s determinations of what constitutes a “wetland” under current agreements and the agency’s responses to suspected violations, which Cramer calls “heavy-handed.”

Scott VanderWal, South Dakota Farm Bureau

Scott VanderWal, South Dakota Farm Bureau

Easement deeds signed before 1976 did not contain maps or detailed descriptions of easement boundaries. That lack of clarity caused several disputes between North Dakota landowners and the Fish and Wildlife Service. Frustrations over the maps were brought up during a town hall meeting Cramer hosted with Fish and Wildlife Service officials in 2017 and later that year, acting Interior Secretary David Bernhardt promised to update easement maps and create an appeals process for landowners that disagree with the agency.

The agency did update its internal guidance in 2020, before sending out new easement boundary maps overlaid on aerial imagery. But last year, four of the state’s commodity organizations wrote to current FWS director Martha Williams, claiming that some of the maps were inaccurate. Some of the mapped areas, they said, had no existing or recurring surface water or marsh vegetation and others included more acres than what was listed in the agreements.

The groups — which included the North Dakota Soybean Growers Association, the North Dakota Grain Growers Association, the North Dakota Corn Growers Association and the North Dakota Canola Growers Association — also argued that some of the Fish and Wildlife Service’s responses to objections in the appeals process did not include evidence or analysis from the agency.

Williams, in response earlier this year, defended the maps, saying they all showed “clear indications of wetlands.” She pointed to an objection rate of 10% in the appeals process, which she said signified that most landowners found the new map determinations acceptable. She also promised to ensure that final acreage numbers match up to the totals included in the contracts.

But Cramer told Agri-Pulse he is concerned the agency still isn’t taking farmers' objections seriously, pointing out that not a single farmer has won an appeal with the agency. He also said that Williams’ response came over a year after the commodity groups had sent their letter.

“They’re supposed to be partners,” Cramer said. “The problem is if you’re in a partnership with the federal government, you’re the junior partner every time.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.