USDA is promoting new crop insurance choices this year, even as strong commodity prices and elevated production costs are making existing coverage even more vital to farmers, says Marcia Bunger, administrator of the Risk Management Agency.

RMA has launched an effort to try to sell insurance companies and agents on the Whole Farm Revenue Protection policy, which has seen declining sales in recent years. Hoping to entice more specialty crop operations to buy WFRP, RMA has doubled the maximum insured revenue this year to $17 million.

That educational effort, plus a requirement for recipients of disaster assistance to buy crop insurance, may help increase interest in Whole Farm policies, Bunger said in an interview with Agri-Pulse.

“You're going to see individuals that will need to carry crop insurance in some shape or form,” Bunger said.

USDA has paid farmers $7.3 billion through the Emergency Relief Program for losses in 2020 and 2021, and farmers who take the money are required to buy crop insurance for the next two available crop years or purchase coverage for non-insurable crops through the Non-insured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP).

Also this year, USDA is enhancing revenue protection insurance for oats and rye and is expanding the availability of the PACE revenue protection endorsement that allows corn growers to insure against yield losses when they’re unable to make a split application of fertilizer.

RMA also is allowing farmers to insure double cropping in more counties this year in an effort to prevent shortages in global grain supplies. The extent to which farmers are increasing their insured double cropping won’t be known until later in the year when RMA gets the required paperwork from growers.

What won’t take place this year is another round of premium subsidies for growers who plant cover crops. USDA used pandemic relief funding to make $5-an-acre payments for cover crops planted in 2020 and 2021. The department doesn’t have the money to do a third round, Bunger said.

Meanwhile, Bunger is encouraging all growers to view crop insurance as a marketing tool and consider forward-selling some of the bushels for which they’ve insured their production.

“With these historically high prices … for a lot producers you can lock in a profit,” she said.

“There are some (farmers) that have the thought that, ‘I'm not selling anything until I have it in the bin.’ And I respect that, but there's many others that use their crop insurance as a marketing tool,” she said. “You're already paying the premium so you might as well get the most out of it that you can.”

Despite the struggles of Whole Farm, the amount of land covered by insurance has grown sharply in recent years largely because of the growing popularity of Rain Index policies, which trigger indemnities for rangeland and forage during periods of low precipitation.

Last year, farmers bought crop insurance on 493 million acres nationwide, up from 283 million acres in 2012. Rain Index policies covered more than 250 million acres in 2022.

Crop insurance proved vital to many growers across the Plains and West who were caught in a severe drought. Farmers have been paid $15.5 billion in indemnities on 2022 crops so far, the largest amount by a healthy margin since 2012, another year of widespread drought.

As of Monday, some $11.1 billion in indemnities had been paid on 2022 crop revenue protection policies, including $3.9 billion on corn and $2.6 billion on cotton. Another $2 billion in indemnities have been paid on Rain Index policies.

Texas producers lead the nation in 2022 indemnities with $3.8 billion, followed by Kansas with $1.9 billion and Nebraska with $1.2 billion. California, North Dakota and South Dakota have all received about $1.1 billion each.

Bunger believes demand for Rain Index insurance will continue to grow because there are still many areas where producers don’t know about it. The Trump administration was considering steps to reduce the frequency of Rain Index indemnities, but the Biden administration is leaving the program alone.

Here is a look at RMA’s latest initiatives:

Oats and rye: They are eligible for better revenue protection in 2023, similar to what’s been available for barley and wheat. RMA previously set insurance prices for oats and rye up to 11 months before harvest. Now, the insurance price will change to follow increases in crop prices.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse by clicking on our link!

During the 2021 and 2022 crop years, oat prices increased 30% after the insurance prices were set, which meant that the insurance coverage was worth much less than the crop, according to RMA.

Whole Farm: RMA has been holding educational “roadshows” to promote both WFRP and the similar Micro Farm revenue policy that is targeted to smaller operations. The Micro Farm insurance limit has been raised to $350,000. The latest roadshow was Tuesday in Davenport, Iowa. The next one will be Feb. 25 in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Bunger hopes agents will be talking to clients about the policies. “I still think there's huge room for improved education with actual farmers,” she said.

Unlike traditional, crop-specific policies, the Whole Farm and Micro Farm policies are designed to trigger indemnities when a farm’s entire revenue falls below an insured amount. Sales of WFRP have fallen every year since peaking in 2017 with 2,833 policies. Some 1,811 were sold in 2022, with more than 700 of those purchased in a single state, Washington.

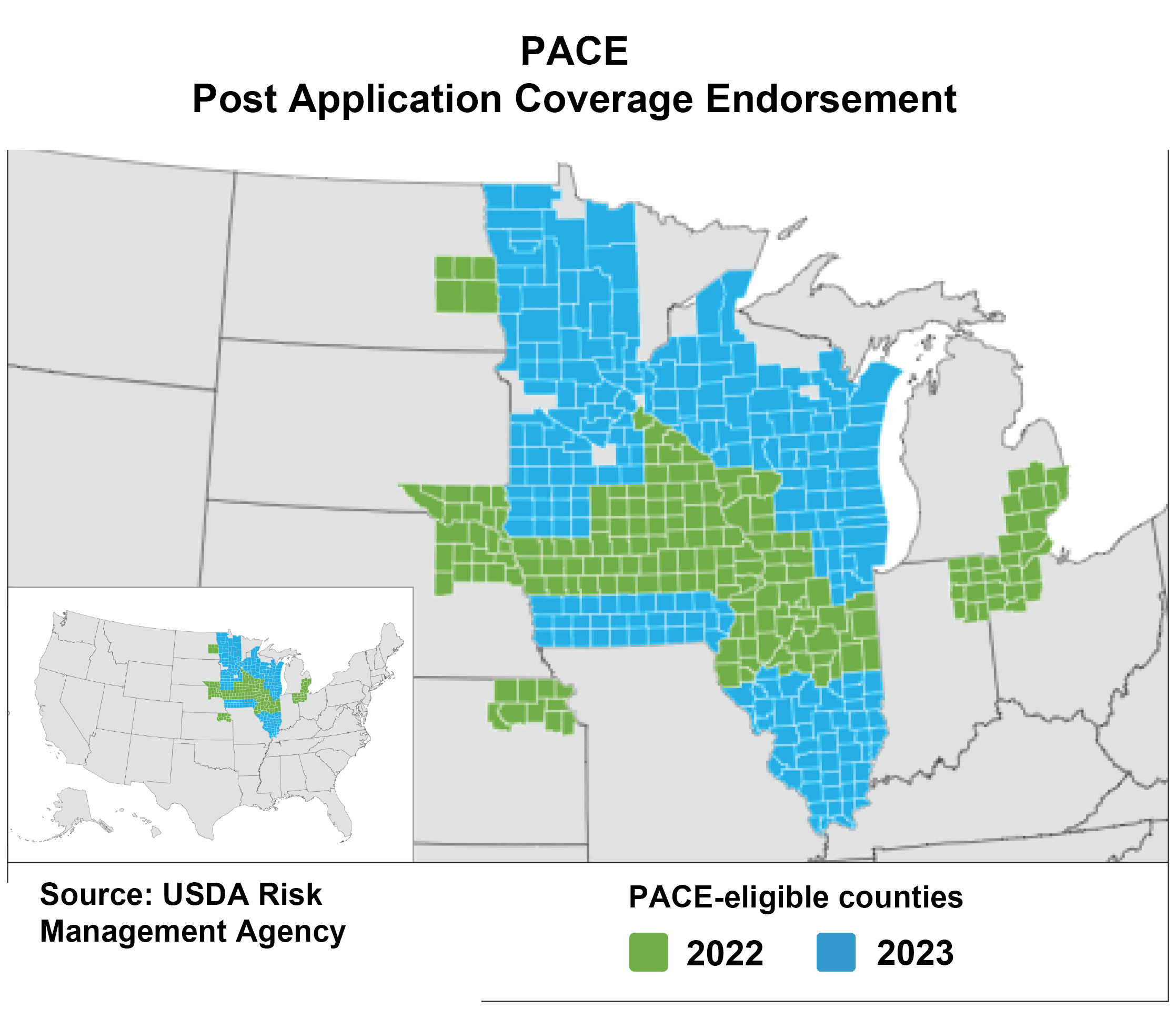

PACE: Just 66 corn growers bought the Post-Application Coverage Endorsement (PACE) when it was sold for the first time in 2022 in select counties in 11 states. This year, it will be available in most counties of Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin and also in areas of Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, and South Dakota.

The product is designed to protect farmers who are unable because of field conditions to make a fertilizer application during the growing season.

Splitting fertilizer applications can reduce nutrient runoff as well as save a farmer, but whether producers buy PACE depends in part on how wet they think their fields will be, Bunger said. The price of corn also is a factor, since higher prices provide an incentive to apply more fertilizer. The decision whether to split fertilizer applications “is very individually driven,” she said.

The Illinois Corn Growers Association ran multistate radio ads last fall and will be starting a digital campaign to promote the product ahead of the March 15 deadline for purchasing insurance, said Megan Dwyer, director of conservation and nutrient stewardship for the group.

The group also is planning to do mailings over the summer, targeting farmers who are making decisions about fall fertilizer purchases.

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.