The feral hogs began to show up at Tommy Henderson’s north Texas farm in the early 1990s. By 2002, they were “everywhere.” Henderson still can’t get rid of them.

The wild swine have rooted up Henderson’s wheat fields, left potholes the size of “a No. 2 wash tub” in his pastures and spread E. coli to his cattle. He estimates they cause $15,000 to $20,000 in damage to his farm annually, despite around 300 and 400 local hogs being trapped or killed each year through damage control efforts.

“They’re multiplying so fast,” Henderson said. “We may be keeping ‘em in check, but we’re not gaining on them.”

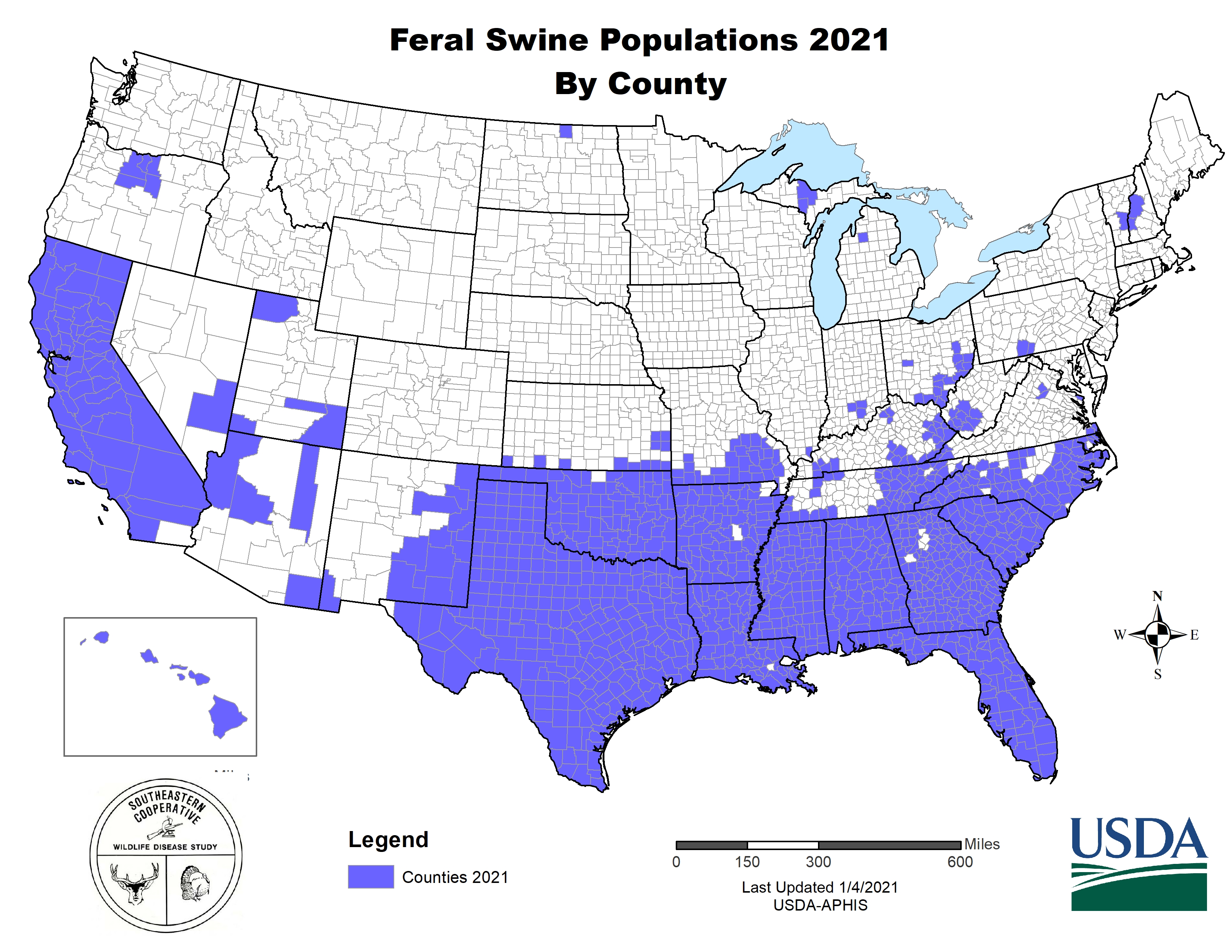

Over 6 million feral hogs, an invasive species first introduced by explorers in the 1500s, now roam at least 35 states in the U.S. and, according to American Farm Bureau Federation economist Daniel Munch, have become a nuisance for approximately 1.1 million farmers. These producers have found some help from the Agriculture Department, which has been given money to put towards feral swine control, though funding in the 2018 farm bill for one of the agency’s control programs is set to expire later this year.

Feral hog damage in one of Texas farmer Tommy Henderson's fields. Photo provided by Tommy Henderson.

Feral hog damage in one of Texas farmer Tommy Henderson's fields. Photo provided by Tommy Henderson.

The Agriculture Department once estimated that feral hogs caused more than $1.5 billion in damage across the U.S. annually, but upped that figure in its 2023 budget justification to $2.5 billion. Populations are dense throughout the South, though the beasts have also made their way into California, Oregon, Vermont, New Hampshire, Michigan, Wisconsin, Hawaii and North Dakota.

The hogs uproot crops and trample fields in their search for food. Munch has heard stories of the beasts wiping out entire soybean crops and attacking young lambs in the pasture.

Since they have no natural predators, the animals also cause water quality problems by wallowing along riverbanks. They can carry pathogens like brucellosis, swine influenza, salmonella, hepatitis and pathogenic E. coli, and populate quickly, with sows capable of producing up to two litters of five to 10 piglets every year.

“The population numbers can really move exponentially,” William Green, the catfish, forestry and wildlife divisions director for the Alabama Farmers Federation, told Agri-Pulse.

The problem has become so bad that federal government initiatives have been created to curb their spread. USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service receives $33.5 million from Congress annually for its National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, which began in 2014 to reduce damage in high-population states and eliminate the feral swine presence in low-population ones.

Congress also armed the USDA with an additional $75 million for feral swine control efforts through the 2018 farm bill. The funding for this program, dubbed the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program, was split evenly between the Natural Resources Conservation Service and APHIS.

NRCS’s share of the funding has gone toward providing producers with cost-share assistance to purchase traps and funding to support conservation efforts sponsored by the agency. The funding went to pilot projects in 12 states, with the agency providing up to 75% of the total project costs and non-agency partners providing the rest.

APHIS’s portion of the funding has been targeted towards swine removal in the same project areas, which span 1.93 million acres of land with high densities of feral hogs. Mike Marlow, the assistant program manager for the agency’s National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, told Agri-Pulse that this funding allowed farmers in some previously high-population areas to grow crops they hadn’t been able to in years.

“The farm bill has certainly been a boost to allow us to get the areas where our funding didn’t allow us to get before,” Marlow said. “It’s allowed us to expand our footprint, it’s allowed us to hire boots on the ground and actually get to areas where we’ve been challenged financially to get to.”

Through both of its programs, APHIS has successfully eliminated feral swine from five states: Idaho, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey and New York. Six others — Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin — have been moved to “detection status”, which means they are presently being monitored to determine whether feral swine have been eliminated.

But high populations are still persistent across much of the Southeast. Texas is believed to be home to about 3 million feral hogs, around half of the total U.S. population, and state APHIS director Michael Bodenchuk said populations are far too large for his office to focus on statewide eradication. His team has instead been focused on mitigating damage and eliminating local groups.

“Clearly other states don’t want to be where we are,” Bodenchuk told Agri-Pulse. “It’s become the majority of our work because we didn’t get on top of it early.”

Don’t miss a beat! It’s easy to sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! For the latest on what’s happening in Washington, D.C. and around the country in agriculture, just click here.

The office has made some progress, however. With the farm bill funding, Bodenchuk said his team was able to “really get aggressive” in Dallum County and eradicate the local population for the first time. Crop losses and pasture damage decreased 70% to 80% in Oldham, Potter and Randall counties after treatment from the agency.

One of the measures the agency uses to reduce hog populations is shooting them from helicopters. Henderson, who farms in one of the counties receiving farm bill funding, said the agency flies a helicopter over his land around every three months, often killing 200 or 300 in a day.

Alabama is another state where hog populations have reached worrying levels, with Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville saying during a recent Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee hearing that he can’t go anywhere in his state without hearing farmers and foresters talk about feral swine damage to their crops.

Most of Alabama’s feral hog population is located in the southern third of the state, where the region’s peanut farmers have seen significant losses.

Wade Helms, who grows peanuts in three counties in southeast Alabama, said he has seen damage in up to 30% of some fields near creek beds where the hogs live. He has been seeing these populations decline due to population control efforts from several area farmers, however.

Helms has been able to purchase a trap that would normally cost around $9,000 or $10,000 with the help of NRCS, which covered around $6,000 of the purchase. He’s also been able to hire trappers with financial assistance from the agency, which have helped him kill 300 to 400 hogs over the last two years.

“Not only did they help finance the trap that I bought, but they’re also paying professional trappers to come out and ease the burden on me and other farmers,” Helms told Agri-Pulse. “It’s really made a huge impact in my area.”

APHIS’s damage management program relies on annual congressional appropriations. Both the AFBF and the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies would like to see funding for the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program continued, or even increased, in the next farm bill.

“The farm bill funding is very important to keeping these programs running and keeping these populations down,” Kalina Vatave, AFWA’s agriculture policy program manager, told Agri-Pulse.

Rep. Monica De La Cruz, R-Tex., proposed a bill last month that would extend the farm bill program for five more years. Cruz, in written responses to Agri-Pulse questions, said she sees the 2023 Farm Bill as a potential vehicle for her measure.

Munch, the AFBF economist, said some state-level Farm Bureaus want APHIS to take the lead role in federal swine control efforts and adjust the farm bill language to require “cooperation” between the two agencies, rather than “coordination.”

The organization also wants states with new or no feral hog populations to ban commercial hunting of the animals, according to a report by its feral hog study group.

"When an invasive animal species is assigned value, such as value in the meat or hide or value in recreational hunting, it incentivizes maintaining a stable population over the long term," the report said.

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.