Western producers in areas once dealing with devastating droughts scrambled to keep their livestock safe and fed this winter as a series of storms caused record-breaking amounts of precipitation. Now, the snowpack is beginning to melt, fueling concerns about potential flooding.

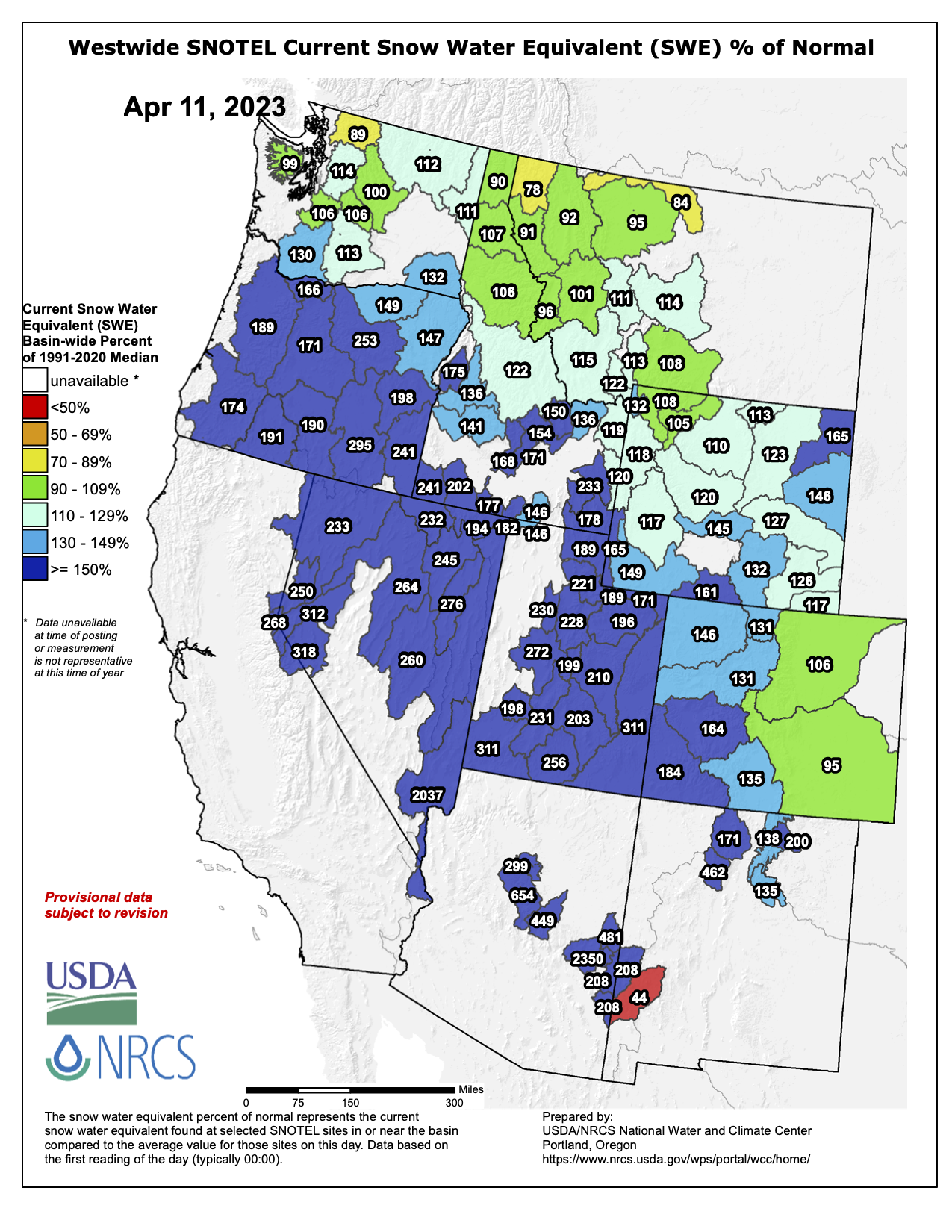

Snowpack levels in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and some parts of New Mexico and Colorado are 150% above the 20-year median. Some of the precipitation that fell in this region may have bypassed the Pacific Northwest, much of which is seeing lower-than-normal snowpack levels this year.

The potential for flooding depends on how fast warm weather sets in.

“What we hope is it doesn’t warm up fast,” Utah rancher ValJay Rigby told Agri-Pulse.

The first round of winter precipitation began in a two-week stretch in early December and the second spanned four weeks after Christmas, USDA meteorologist Brad Rippey said, providing some relief from long-standing drought conditions. Then, a five-week period of high precipitation hit the same regions in late February, causing record-setting snowpacks in some areas.

“This is a once-in-a-generation type winter in terms of snowpack,” Rippey told Agri-Pulse.

The precipitation will help refill reservoirs, add moisture to parched soils and help recover dried-up rangelands. California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, and Colorado, covered with swathes of red on last year’s drought monitor, are now seeing varying shades of orange, yellow and white.

But excess precipitation has come with its own challenges for producers, especially those who raise livestock. It’s difficult for many to bemoan the much-needed moisture, but the excess snow has blanketed pastures cattle rely on for food, limited ranchers’ access to their herds and raised calf mortality rates.

“We’re hitting calf losses of up to 30% to 40% in some of our hardest-hit areas,” Utah Agriculture Department Director Craig Butters told Agri-Pulse. “A lot of the cattlemen are having a difficult time getting a dry, solid base for their cattle to calve on.”

Large drifts are covering rangelands, preventing cattle from accessing food and forcing producers to turn to other alternatives like hay, which can cost over $300 per ton in California, Nevada and Arizona.

“Our native bushgrasses and grasses typically aren’t that tall to begin with,” said Jon Griggs, the ranch manager at Maggie Creek Ranch near Elko, Nevada. “And then put that much snow on top of it and those subzero temperatures. Cows are all of a sudden in a very bad place.”

Griggs, who helps oversee a 2,500-head cattle operation, said the ranch has roughly spent at least half a million dollars purchasing and shipping supplemental feed this year. They don’t typically purchase hay, instead relying on their own hay crop to satisfy the needs of the cattle when not on pasture. Nevada’s winters are usually mild enough to allow producers to graze late into one year and early into the next, which helps limit the amount of hay that is needed, Griggs said.

Cattle walking down a plowed track to get to feed ground. (Photo: Jennifer Whitely) “You keep thinking there’s an end in sight and it keeps not coming,” Griggs said. “It’s just really tough on people.”

Cattle walking down a plowed track to get to feed ground. (Photo: Jennifer Whitely) “You keep thinking there’s an end in sight and it keeps not coming,” Griggs said. “It’s just really tough on people.”Bureau of Land Management rules prevent farmers from bringing alternate feed sources to livestock on public lands, which constitutes 63% of Nevada’s acreage. The agency does grant waivers on a case-by-case basis, an option that producers have tried. Others have been able to truck their livestock from federally-owned land to their private pastures.

But some ranchers facing large drifts lacked access to these rangelands, reliable transportation or space on their own farms, making it difficult to move their livestock or get feed to them.

Between half to three-quarters of Nevada’s beef herd is being affected to some degree by winter conditions, said Nevada Agriculture Department Director J.J. Goicoechea. The well-being of producers is also a concern in the state, with many being trapped and stranded on their farms.

“We’re awfully concerned about the welfare of our humans, of those ranching families,” said Goicoechea.

And as rising spring temperatures melt the record-high snows, flooding presents another threat in the region. California has already become one prominent victim, with dairies, strawberry fields and orchards underwater.

Rigby, who raises around 100 mother cows near Newton, Utah, has been hit by one storm after another, each one bringing between 12 and 14 inches of snow. He said the most snow he had on the ground at one time was just over three feet.

The snow on Rigby’s ranch caused significant losses — he estimates a 20% calf loss rate — during this year’s calving season.

“They not only died, but I lost them,” Rigby said. “I couldn’t find them in the snow drifts.”

Buttars and Goicoechea, along with state secretaries of agriculture in Colorado and Wyoming, sent a joint letter to Farm Service Agency Administrator Zach Ducheneaux on Feb. 9, asking for “flexibility” and “innovative ideas” to expand eligibility and use of emergency programs to help farmers. Assistance with supplemental feed and water, additional locations to move livestock to and snow removal assistance were especially needed, they said.

“Any consideration you could provide to this unfortunate circumstance would be sincerely appreciated,” the state agency heads wrote. “The expertise that you and your staff have with the idiosyncrasies of your programs and budgeting authorities could prove to be very helpful.”

Nevada’s congressional delegation followed with their own letter to Ducheneaux on March 9. They asked for the department to consider providing “immediate assistance” to Nevada producers and requested a “prompt response” to the state department heads’ letter.

The emphasis from state agriculture officials and lawmakers highlights the severity of the situation, Griggs said.

“This isn’t just a bad year. This isn’t one of those one-in-10 years that we can plan for with the help of a program,” Griggs said. “This is a serious, significant, really bad event that we have no experience with and no history with.”

Ducheneaux responded to Wyoming Agriculture Department Director Doug Miyamoto in a letter that said the agency had declared nine Wyoming counties as primary natural disaster areas on March 29. An agency spokesperson told Agri-Pulse on Monday that the agency would be sending letters to the other states in “the next few days.”

Don’t miss a beat! It’s easy to sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! For the latest on what’s happening in Washington, D.C. and around the country in agriculture, just click here.

Ducheneaux, in the letter, said the Livestock Indemnity Program could be used by cattle producers experiencing livestock deaths exceeding normal mortality due to the winter storms. The Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP) could also help offset additional feed expenses incurred by producers, Ducheneaux said.

Ducheneaux, in the letter, said the Livestock Indemnity Program could be used by cattle producers experiencing livestock deaths exceeding normal mortality due to the winter storms. The Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP) could also help offset additional feed expenses incurred by producers, Ducheneaux said.

“My staff and I are open to suggestions on any assistance needs expressed by Wyoming farmers and ranchers and willing to review current programs and policies to offer flexibilities within our authority to implement and we’d be glad to work with your Department of Agriculture to share our improvements to these programs,” Ducheneaux told Miyamoto.

The surge in precipitation may still not be enough to prevent forest fires from breaking out across the West or completely offset low water levels in the Colorado River, Rippey said. But soil moisture has generally been replenished in a lot of areas, though it may take a couple of years for pastures and rangelands to fully recover.

Both Griggs and Rigby agree that the winter moisture will provide critical help down the road.

“We needed every bit of what we got,” Griggs said. “It’s just been hard to take.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.