The issue of investors buying up prime agricultural land has reached a new pinnace, with Silicon Valley developers behind a major land grab in Solano County. Frustrated lawmakers hoping to thwart the takeover are surveying the few policy tools at hand. But farmers and ranchers are warning the problem extends well beyond land purchases and any silver bullet solution.

Under the corporation Flannery Associates, four prominent investors in the tech sector began purchasing agricultural land in 2018 in an area surrounding Travis Air Force Base. They have spent more than $800 million to acquire 400 parcels and 55,000 acres of land in the Northern California county, according to The New York Times. The company plans to override local zoning laws to build a new ecofriendly city near Fairfield.

That has raised alarms for state Senator Melissa Hurtado of Bakersfield, who has long warned of such threats to agriculture and food security.

She has led the charge in Sacramento over the issue. The moderate Democrat joined forces with Sen. Dave Cortese of Silicon Valley last year to request the U.S. attorney general investigate potential water profiteering through land grabs during the drought. They worried hedge funds were buying up property for the water rights through anti-competitive practices.

Hurtado, who chairs the Senate Agriculture Committee, has also raised eyebrows in the agriculture community for her proposal to bar foreign governments from purchasing farmland and continues to field calls from farmers feeling threatened to sell their land to investors.

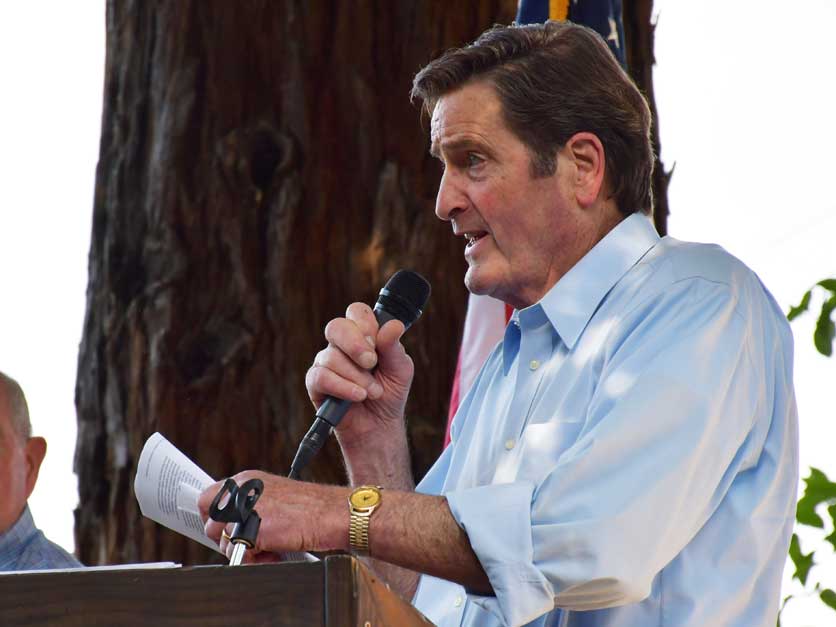

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif.

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif.In response to the revelations over Flannery Associates, Hurtado held an informational hearing on the issue with testimony from many of the people who “continue to motivate me and help me bring transparency into what is happening,” she said. Sen. Bill Dodd of Napa shared in her sentiment, saying his phone has been ringing off the hook from constituents alarmed by a company “operating in the shadows” to develop large swaths of land.

The greatest frustration came from Rep. John Garamendi, who represents a portion of the Sacramento Valley.

“Farmers and ranchers are facing a harrowing choice of sell or risk getting sued by wealthy out-of-town speculators who want the land,” said Garamendi. “Flannery Associates is using secrecy, bullying and mobster tactics to force generational farm families to sell.”

He noted that the company has hired “big city lawyers” to file federal lawsuits claiming a restraint of trade against seven farm families who refused to sell.

“Those Silicon Valley bigwig billionaires should be ashamed and they should be held to account,” he added. “They're off to a terrible start at earning the community's trust.”

He pushed for expanding the use of state and federal conservation easements in the area to prevent urban encroachment around the base. Garamendi and his wife were the first to donate a family estate to the California Rangeland Trust in 1999. As a member of the House Armed Services Committee, Garamendi has worked to increase funding for a Department of Defense program to purchase easements near military bases. The program has spent $173 million in California, with $40 million more available this year.

Jamie Fanous, policy director for the Community Alliance with Family Farmers, said the only entities able to purchase land in California are large corporate hedge funds, and not local farmers. Fanous pointed to San Bernardino and Riverside counties, once the center of citrus production in the state, and charged that a surge in warehouse development destroyed the farming community overnight and impacted food security, local air quality, housing and community health.

“The playbook for all of these entities is the same,” said Fanous. “If you refuse and they do not get what they want, they will likely sue the small farming communities out of existence. It is a chilling reality, but we are seeing it play out in many instances in California.”

Christopher Cabaldon, a former mayor of West Sacramento who is now running for Dodd’s seat when he terms out of office, lamented that the Williamson Act for conservation easements “has not really been effective” in preventing such acquisitions, since buyers are often willing to pay the penalty of 15% of market value for terminating a contract early. The California Environmental Quality Act, often wielded by special interests to block developments, would be “completely underpowered” with land conversions of this scale.

He did offer some hope for stalling Flannery Associates through the local agency formation commission, or LAFCO. The state agency is not subject to county initiatives and must consider sustainable community plans through a law enacted by the Legislature as well as state and federal transportation plans—hurdles the proposed development is unlikely to meet. LAFCOs, however, fall short with water implications that lie outside their zones, and the Flannery plan poses sweeping water challenges across counties. The issue is further complicated with the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which has led to a rise in land values for properties with two sources of water, according to Madonna Lang, a realtor who has spent nearly a decade selling agricultural land in the region.

Don't miss a beat! Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! For the latest on what’s happening in agriculture in Washington, D.C. and around the country, click here.

Sen. Melissa Hurtado, D-Bakersfield

Sen. Melissa Hurtado, D-BakersfieldYet Cabaldon warned it may already be too late for the farmers and ranchers who have successfully resisted the land grab. Agriculture, he explained, depends on a critical mass in the region to maintain support infrastructure like processing facilities. In the urbanization process, ranchers face further restrictions, losing leases to graze on nearby property, for example. The local fire protection district, controlled by a new entity that wants to build more stations, raises its assessments, leading to higher taxes for landowners in order to finance projects that serve the larger area and not the ranchers.

“It's almost impossible for them to survive in this space,” said Cabaldon, adding that it is hard to undo the damage once it has begun. “You can't reset the clock.”

He estimated that 50 state agencies and 20 local ones will be reviewing the Flannery proposal. But by the time they do, they will be reviewing a project long after the farmers have left.

“The current law allows for the complete erasure of the status quo prior to the very first public hearing or vote,” he said.

Ranchers are increasingly vulnerable to such outside pressures. According to Michael Delbar, CEO of the California Rangeland Trust, they are struggling with tight profit margins due to rising prices for equipment, feed and fuel, along with escalating labor costs and expensive state air quality mandates. He noted that California spends just 11 cents per capita on conservation easements—compared to Delaware’s $6. He estimated it would cost $250 million to protect the 102 ranching properties currently seeking help from the trust.

Taylor Roschen, an agricultural policy advocate at Kahn, Soares & Conway, pointed out that water quality fees alone have risen 150% in the last decade.

“Even if you could overcome the landownership challenges that dominate a lot of the conversation today,” said Roschen, “there's real questions about whether or not you could even afford that land to farm.”

For more news, visit Agri-Pulse.com.