(This is the third article in our new Agri-Pulse series, “The seven things you should know before you write the next farm bill.” Each segment provides important background and “lessons learned” that can help inform and stimulate debate before formal work starts on writing the next farm bill.)

WASHINGTON, Feb. 26, 2017 – When Sen. Debbie Stabenow sat at the helm of the Senate Committee on Agriculture for the first time in 2011, there was a row of seats filled by ranking member Pat Roberts, R-Kan., and other Republican senators on her left. Democrats lined up in chairs on the right. Staff filled in all along the back walls of the relatively small, but cozy committee room on the third floor of the Russell building.

When it came time to write a new commodity title for the farm bill, her view could have been described much differently. She was looking at senators from three distinctly different regions: the South, the Midwest, and the upper Great Plains. Each had their own ideas about what farmers in their respective states wanted for risk management.

For example, in Kansas, farmers told Roberts about the importance of protecting and enhancing crop insurance.

“If priorities must be declared, then a strong and viable crop insurance program will top our list,” noted Kansas Farm Bureau President Steve Baccus in testimony at the 2011 farm bill field hearing in Wichita. “Viable risk management tolls have become the most dependable resource producers can access to ensure a revenue stream and minimize the inherent risk that weather injects into a farming operation.”

It was a theme repeated often as other commodity group leaders testified.

“The thing you would be most concerned about losing would be crop insurance – is that a fair statement? Anybody disagree with that?” Stabenow asked during the hearing.

No one disagreed and, frankly, no one was surprised.

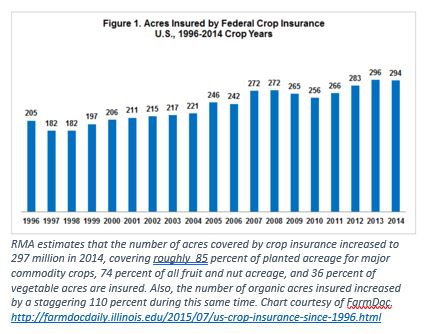

Growers of over 100 different types of crops had increasingly purchased crop insurance as a risk management tool – aided in part by an average 60 percent premium discount provided by the federal government. Acreage insured climbed dramatically, from 99.6 million acres in 1994 to over 246 million acres by 2011.

Unlike the costly and uncertain ad hoc disaster programs of the past, crop insurance provided a more reliable and predictable way for both farmers and their lenders to calculate some of their potential risks.

Unlike the costly and uncertain ad hoc disaster programs of the past, crop insurance provided a more reliable and predictable way for both farmers and their lenders to calculate some of their potential risks.

But it was a much different story when it came to writing the commodity title.

Farm bill veterans know that some of the biggest fights in farm policy usually fall along regional rather than party lines. Depending on who is in the House and Senate committee seats, farm bill strategies need to vary in order to pass a bill out of committee that can meld those different interests.

Farm bill veterans know that some of the biggest fights in farm policy usually fall along regional rather than party lines. Depending on who is in the House and Senate committee seats, farm bill strategies need to vary in order to pass a bill out of committee that can meld those different interests.

During an interview with Agri-Pulse, Roberts – who previously served as chairman of the House Agriculture Committee and now chairs the Senate Agriculture Committee – recalled advice that he got from former House Agriculture Chairman Kika de la Garza, D-Texas, when he first took the helm of the panel in 1995.

“He said, ‘You aren’t going to have any problems with our side. I’ll take care of our side. You know where we are coming from and you can deal with that. Where you are going to have problems is on your side’”

“And it’s true,” Roberts said, “because a lot of your friends expect you to do things for them that you cannot do or you shouldn’t do.”

Regional divisions expected?

In many ways, regional divisions are expected because farmers across the U.S. grow a lot of different crops and raise livestock under a variety of conditions.

The production risks involved in producing a bountiful crop, milking healthy cows, birthing cattle, pigs and lambs, are almost too numerous to count. On any given day, a producer might wonder: Will it rain? Will it rain too much? Will my animals be killed in a freak blizzard? Will my chicken flock get struck by disease and have to be destroyed? Will my vegetables be hit by an early frost?

Depending on how the production varies – both in the U.S. and around the world – there is also the price risk. Prices can respond quickly and dramatically – up or down – if you are a corn and soybean farmer and a major player in terms of global production. For example, U.S. producers benefit when South American corn and soybean farmers have a drought – with production falling short of market expectations - and vice versa.

But for cotton, where the U.S. has had such a small share of the market, a bad U.S. crop won’t be much of a blip in global trading.

There are also a multitude of financial risks: What if market prices skyrocket but a farmer doesn’t have any crops or livestock to sell? What if interest rates shoot up and he or she can no longer repay loans on assets or operating expenses? What if other countries manipulate their currencies in a way that make it more difficult to export U.S. agricultural products?

And finally, one can’t rule out the political risks that have battered farm incomes around the globe over the years. What if the president declares a grain embargo, as President Jimmy Carter did in 1980 to respond to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan? Grain prices plummeted as a result. Almost two decades later, the Russian government shut off exports to the world in response to drought and wildfires at home, sending commodity prices soaring.

As a result, “Wheat prices jumped over 7 percent in less than two months,” noted Stabenow in her first official address as chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee in January 2011. “That’s why, as we look forward to writing the next farm bill, I am fully committed to a strong safety net,” she told members attending the Michigan Agribusiness Council annual meeting in 2011.

Underlying all of these risks is a more fundamental question: What is the proper role for the federal government in managing risks on the farm?

In the U.S., as well as in countries around the world, governments have employed a wide variety of programs and tactics to address risks on the farm, including disposal of surplus crops and livestock, limits on production, payments when prices drop below certain levels, environmental and rural development payments, ad hoc disaster assistance and crop insurance.

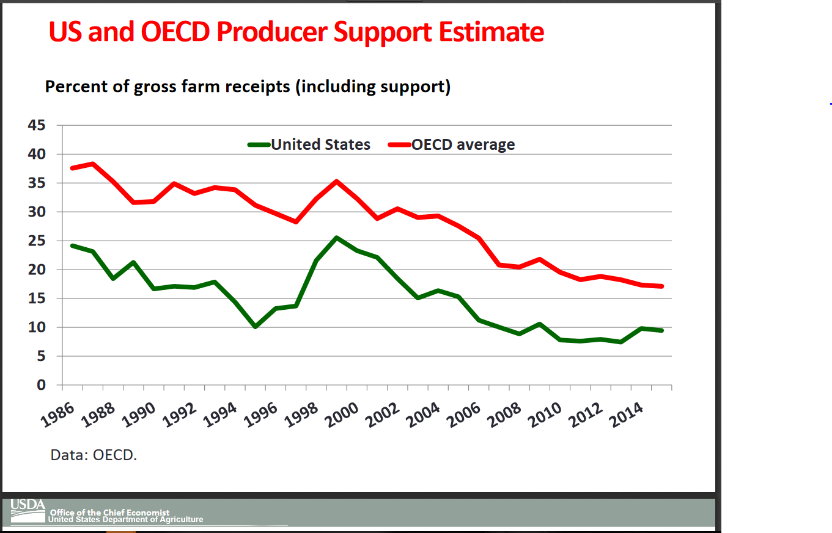

With the exception of the late 1990s, overall U.S. support has declined over the last few decades, USDA Chief Economist Rob Johansson pointed out in a recent presentation (see chart).

Essence of the farm safety net

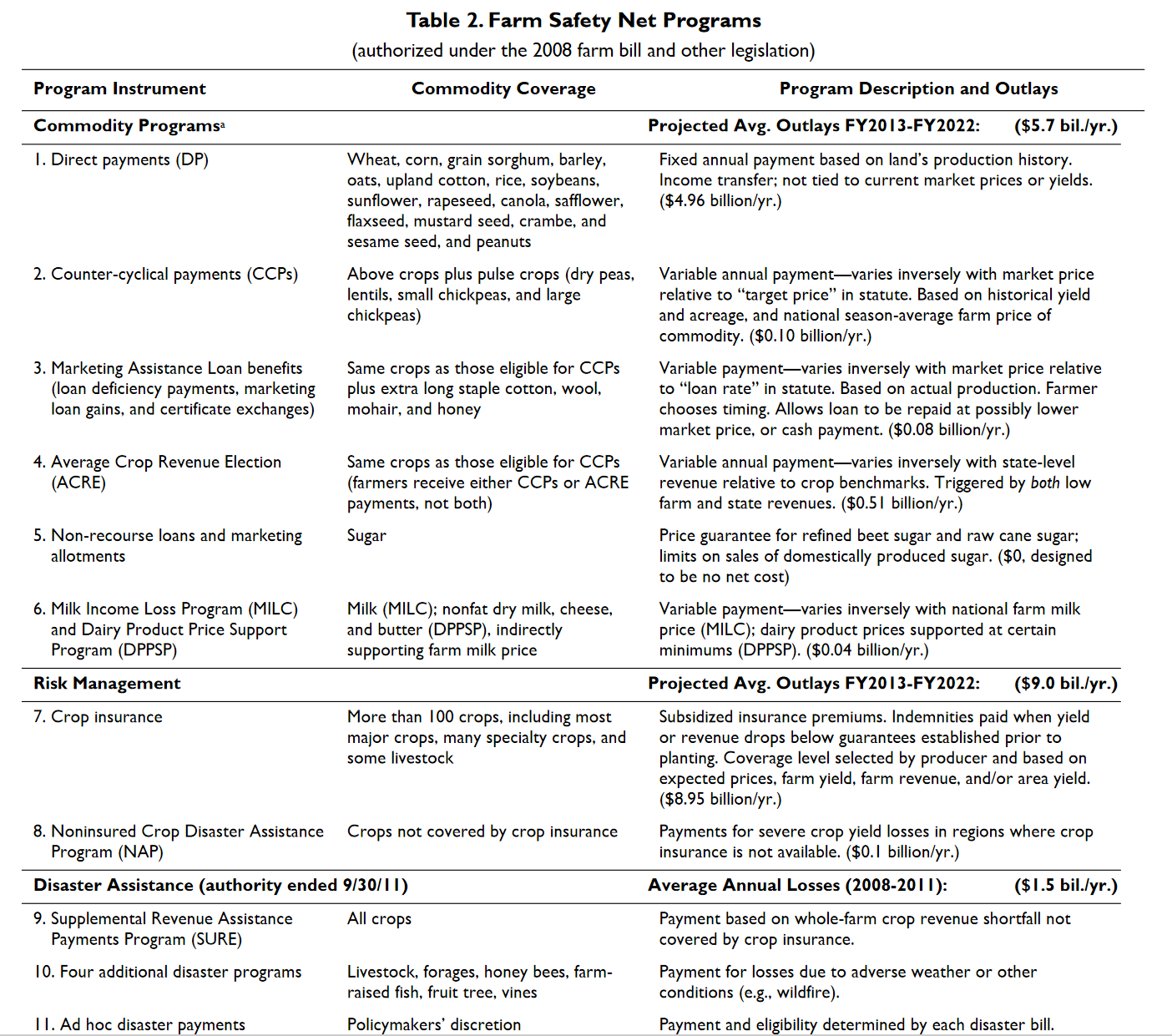

Since the Great Depression in the 1930s, the federal government has often responded to disasters on the farm with attempts to better manage risk, but some of the responses have worked better than others. In modern times, the Congressional Research Service noted that there is a collection of programs that make up the “farm safety net.’ These include:

1. Farm commodity price and income support programs under Title I.

2. Federal crop insurance under the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980

3. Disaster assistance programs under Title XII of the 2008 farm bill.

In a 2012 report on Farm Safety Net Programs, CRS provided this overview of programs that were authorized in the 2008 farm bill:

By the end of the 2008 farm bill, it was widely accepted that “ad hoc” disaster programs were not effective. Oftentimes, Congress lagged for years in making payments and farmers sometimes went out of business during the wait. The complicated Supplemental Revenue Assistance Payments Program (SURE) was not viewed as very helpful or popular either.

What next?

Farm bills are usually more evolutionary than revolutionary, but the budgetary environment in 2011 was ripe for reform. With lawmakers focused on deficit reduction, direct payments – made whether or not farmers planted a crop – were a big reform target for many Republicans and Democrats. And the super-committee process later in the year made it clear that political support for direct payments was waning.

But if direct payments were going to be cut, what type of farm program would replace them?

Members and farm organizations looked at how to divvy up what had previously been spent on direct payments – an estimated $50 billion in baseline spending (over 10 years).

Some of the early discussions centered on a way to address the so-called “shallow losses” not covered by crop insurance. And some stakeholders were unwilling to admit that direct payments would be going away and wanted to offer a reduced level of direct payments in combination with other tools.

- The National Corn Growers Association (NCGA) liked the idea of a revenue-based risk management program, based on yields in multicounty crop reporting districts. They voted in December 2011 to support the “Aggregate Risk and Revenue Management” (ARRM) legislation as introduced by Sens. Sherrod Brown, John Thune, Dick Durbin and Dick Lugar. The AARM program was somewhat similar to a proposal that NCGA had developed – the Agriculture Disaster Assistance Program (ADAP).

- The American Soybean Association (ASA) originally supported “Risk Management for America’s Farmers,” or RMAF, which would establish commodity-specific revenue benchmarks for individual farmers based on historical yields and prices, and compensate them for part of the difference when current-year revenue for a commodity on their farm falls below a percentage of the benchmark.

- Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., originally offered a whole-farm revenue plan for program crops that would make payments when total revenue declines below a guarantee. It would reduce direct payments by 50 percent. Later, he joined with Sen. John Hoeven, R-N.D., and Max Baucus, D-Mon., to introduce the Revenue Loss Assistance Program (RLAP) which eliminated direct payments. At the farm level, it would cover commodity-specific revenue losses greater than 12 percent but not exceeding 25 percent on planted and prevented-planted program crop acreage. It would also continue the counter-cyclical program with 2012 target prices and payments based on 75 percent of base acres.

- The American Farm Bureau Federation originally wanted to continue direct payments and add a “Systemic Risk Reduction Program” to address deep losses resulting from multiyear price declines.

- The National Farmers Union endorsed a 2012 farm bill proposal which incorporated the use of a farmer-owned inventory system, loan rates and set-asides. They called their proposal: Market-Driven Inventory System (MDIS, pronounced Midas).

- Cotton growers wanted the Stacked Income Protection Program (STAX) whereby farmers could buy insurance coverage to protect against shallow losses under an area-wide insurance product with a fixed minimum harvest prices – in addition to a farmer’s individual insurance policy.

- The U.S. Rice Producers argued against a one-size fits all approach to risk management, suggesting that crop insurance was not workable. They wanted a price support program that fit the unique needs of their farmers.

- Rep. Randy Neugebauer, R-Texas, introduced the Crop Risk Options Plan (CROP) to enable farmers who bought insurance to supplement coverage with an area-wide insurance plan to cover shallow losses.

- And dairy programs were up for reform, too. Rep. Collin Peterson, D-Minn., and others offered the Dairy Security Act of 2011, which would eliminate current dairy programs in favor of a voluntary margin insurance program and market stabilization plan.

Ideally, all of these different “reform” options would come up for discussion and debate in the House and Senate Committees on Agriculture. Instead, they became the backdrop for the so-called “Super Committee” process where committee chairs worked in secret to meet deficit reduction goals. Ultimately, Stabenow and Rep. Frank Lucas, R-Okla., who chaired the House Agriculture Committee, proposed a package that cut $23 billion over 10 years, with $13 billion from commodity supports, $6 billion from conservation and $4 billion from nutrition programs.

Former House Ag Chairman Frank Lucas

The final details of the super committee plan were never released but a draft document that was leaked indicated that corn and soybean growers got much of the revenue-guarantee program that they were looking for. Southerners got a price guarantee-option that they wanted, and cotton growers got STAX.

After that process failed, some thought that the parameters were already established in terms of where the policy would eventually end up.

“Many of us assumed the cake was already baked,” recalled one source on the way future policy would develop after the super committee failure. Others saw the super committee’s failure as a chance to start over and write a bill the “old-fashioned” way. And what they lacked in the super-committee negotiations, they wanted more of in the next round.

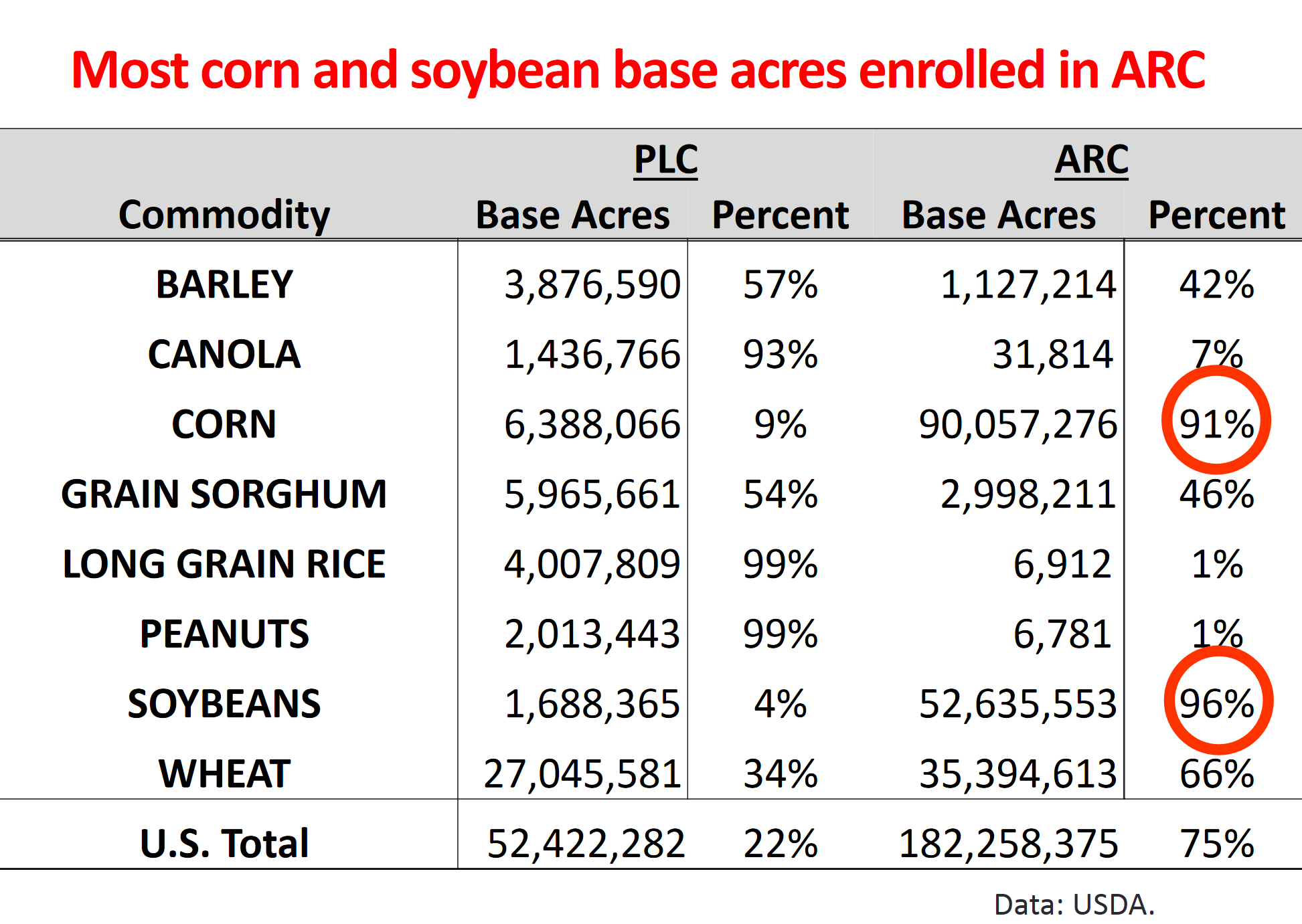

Corn and soybean growers rallied behind a shallow-loss risk management program that eventually became known as the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) program. Rice and peanut growers were more concerned about longer-term price risk and advocated for a program that paid when prices fell below a certain “reference price” level.

One reason why a lot of Midwesterners were more interested in ARC was perception that a lot of their downside risk wasn’t just because of prices but because of yield variability as well,” says a source who was closely involved in the process. “They knew they were coming off relatively good times. Given the budget realities, they didn’t see the possibility that a price-based program would offer the type of support they might need coming off of that high-price situation. That’s why ARC was very attractive option.”

But there was also a concern among Midwesterners that the PLC program, popular with many Southerners, was going to be too lucrative and distort plantings in the South. Rice and peanut producers were quick to point out that their markets weren’t benefiting from the “ethanol boom” which benefitted their Midwestern “brethren” and crop insurance wasn’t as workable for them.

Showdown in Committee

But the Senate Agriculture Committee forged on, trying to find consensus. In an attempt to bring Southerners on board, the cotton program was sweetened a bit, including a change in the acreage cap on land enrolled in STAX. But Southern senators were not able to convince leadership that there should also be a counter-cyclical program in the bill, linked to “target” or “reference” prices that had been historically part of much older price support programs.

The bill eliminated direct payments and the counter-cyclical payment program, enhanced crop insurance and created a new Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) program designed to protect against both price and yield losses at either the individual or farm level. The package was set to reduce the deficit by at least $23 billion.

In committee, an amendment offered by Sens. Max Baucus, Kent Conrad and John Hoeven made three changes to the individual program under ARC: 1) requiring the use of actual production history (APH) instead of a five-year “Olympic” average; 2) including a cost of production cap; and 3) increasing the payment factor to 65 percent, according to a summary of the votes.

Ultimately, Chairman Stabenow produced a bill that senators from two of the three biggest regions represented in her committee room could support. The bill passed out of committee on April 26, 2012, by a 16-5 margin.

Speaking on CSPAN after passage, she described the bill as “fair for every commodity.”

The upper Plains state senators had saddled up with the Midwesterners, and for ranking member Pat Roberts, it was just the type of “posse” the committee needed.

“This is the best farm bill I have seen to date,” said Roberts, a veteran of at least five previous bills. “This is truly a reform bill. The number of programs we consolidated and streamlined is rather incredible,” Agri-Pulse reported after the committee’s vote.

After they voted against the measure, Sens. Thad Cochran, R-Miss.; Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.; Saxby Chambliss, R-Ga.; and John Boozman, R-Ark., vowed to bring up amendments when the bill hit the Senate floor to further protect cotton, rice and peanuts – crops which they argued do not benefit from crop insurance.

“As we move toward a mark on the floor, I hope the issues of rice and peanuts will be given greater consideration,” Chambliss said during the markup. “If enacted under the current proposal, both peanuts and rice are going to take a huge hit.”

Stabenow assured them considerations for Southern crops are already in the bill, including the Stacked Income Protection Plan for cotton.

“It’s not about one region over another, but it is complicated,” she said. “We do have STAX for cotton, a new ag risk coverage program, special prices for rice and peanuts and new crop insurance options. I know this is not all fully developed. We realize we’re not there yet.”

“We’ve known from the beginning as we moved away from direct payments that it would affect the South. This is not a bill without provisions for cotton, rice and peanuts,” Stabenow explained after the markup. “It’s a legitimate issue about transitioning.”

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., the other negative vote in the committee, drew back with concerns about the $4 billion in reductions to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) spending.

Near the end of June, Stabenow and Roberts thought they had more members on board for final passage of a bill, even though they still faced a few troublesome amendments.

Senator Saxby Chambliss, GA

Chambliss of Georgia offered an amendment would have required farmers purchasing crop insurance and receiving a premium subsidy to comply with strict soil conservation erosion standards, known as cross compliance. It’s not that Chambliss was a big fan of the idea, but he wanted to signal his dissatisfaction over Roberts’ support for commodity price protections that were in the bill. The amendment was narrowly approved, 52-47.

But Stabenow and Roberts successfully passed a bill out of the Senate on June 21, with a strong 64-35 margin. Forty-six Democrats and 16 Republicans voted for the bill. Both Independents who caucus with the Democrats, Sens. Joe Lieberman, Conn., and Bernie Sanders, Vt., also voted for it.

Southern Senators were still unhappy.

Boozman, whose state of Arkansas is the nation's largest rice grower, said the Senate bill "will have a devastating impact on Southern agriculture." Chambliss, whose state of Georgia is the national leader in peanut production, complained it "shoehorns all producers into a one-size-fits-all policy" that would force farmers to switch to crops that enjoy better coverage for losses.

Cochran of Mississippi issued a strong statement after the vote. “The ARC program will not sufficiently protect rice and other regional crops from price volatilities that pose less of a risk for commodities sustained by other government policies, such as renewable energy mandates. As such, the Senate bill does not afford these producers sufficient protection against long term, systemic price declines.

“With planting decisions already being distorted by policies outside of the farm bill, it is even more imperative that farm bill policy not further incentivize commodity production in certain regions at the expense of others,” Cochran said.”

Little did anyone expect the role that Cochran would ultimately play in shaping the bill.

In the House, lawmakers had already been firing shots at the Senate version of the farm bill’s commodity title. Rep. Mike Conaway, who chaired the House Agriculture Committee's Subcommittee on General Farm Commodities and Risk Management, described his concerns with what he called the Senate bill’s lack of price protection at a hearing on May 17, 2012.

“The Senate bill also creates a complicated new program that is so lopsided it actually locks in profits for some while denying any safety net at all to others,” he said in opening remarks.

Rice and peanut farmers who testified that day said that crop insurance and the new shallow loss or Agriculture Risk Coverage program were not enough.

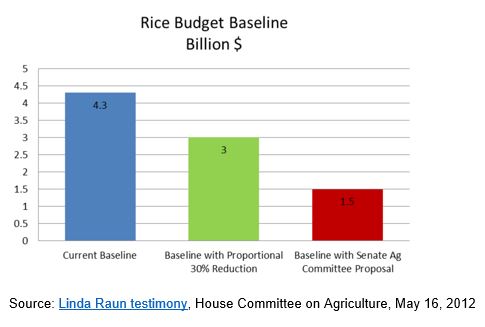

Linda Raun, a Texas rice farmer who chaired the USA Rice Producers Group, said that, without price protection, banks would not lend them money. "We've got to have a farm program that allows us to become bankable." She also criticized the Senate version of the commodity title.

“The rice industry remains concerned that the policy needs of many crops in many regions of the country were largely ignored in that (Senate) bill,” she noted in her testimony. “As you know, farm bills tend to have regional differences due to the needs of different crops grown in diverse regions.

“However, historically, farm bills have been developed that took into account these differences and provided a workable policy for all crops and regions. We are discouraged to see a change in this practice as regards to the Senate Agriculture Committee bill.”

She also pushed back at the regions supporting the Senate package.

“Estimates show that Midwestern and Northern farmers will have an increasingly disproportionate share of the baseline, and Sunbelt crops will be left with a further shrinking baseline coupled with ineffective risk protection for many crops.”

Her testimony was dramatically different from Chip Bowling, a Maryland farmer representing the National Corn Growers Association, who testified on that same day.

Her testimony was dramatically different from Chip Bowling, a Maryland farmer representing the National Corn Growers Association, who testified on that same day.

“NCGA cannot overemphasize the consensus among our membership that the federal crop insurance program is the most critical risk management tool for their farm operation,” Bowling said in his written testimony. “But while individual federal crop insurance policy coverage provides very effective assistance if revenue or yields decline between planting and harvest, it is limited to each policy’s insurance year and is insufficient to insure adequate return on investment over intermediate term, such as for equipment.

So NCGA advocated for a new rolling-average revenue-based program, similar to the ARC program that was included in the Senate bill.

House focuses on price

In the House, Chairman Lucas made clear that the yet-unwritten House bill will include a price-based alternative to meet the concerns of Southern growers like Raun. The House version would indeed include a “Price Loss Coverage,” plan based on new “reference” prices. But it didn’t happen without some rather testy exchanges with those who opposed setting commodity specific price support “reference” prices.

“The behind-closed-door debates between Midwestern and Southern lobbyists and staff were philosophical, regional, and often very personal,” recalls a source who was involved in the discussions. And they often involved other aspects of the commodity title like payment limitations and whether payments should be calculated on planted versus base acres.

“On price risk, it goes to the heart of the fixed price versus rolling average benchmark that underlies the Price Loss Coverage versus Agricultural Risk Coverage fight. Do farmers need a floor price protection that does not change or one that adjusts and expects them to also adjust management when prices are sustained at relatively low levels,” the source explained.

In some respects, the debate also reflected the future outlook for commodity prices. Corn, soybeans and wheat were hitting record highs during most of the period when the farm bill was being written.

But Lucas, who farms in northwestern Oklahoma, reminded his colleagues as he opened up the House Agriculture Committee markup in 2012 that “I know how risky it is to be a farmer….I know at a moment’s notice a dream crop can turn into a disaster.” And as he had frequently reminded his fellow lawmakers, “A safety net is written with bad times in mind. These programs should not guarantee that the good times are the best but, rather, that the bad times are manageable.”

During the voting marathon that kicked off at 10 a.m. and lasted into early the next morning, members slogged through 95 amendments – adopting 44 and eventually withdrawing 28. (For a list of all of the amendments and votes, click here. )

Lucas moved a bill out of his committee by a 35-11 voice vote on July 12, 2012. Some of the most lively debate centered supply management provisions with a new dairy program and the sugar program, but those portions of the debate centered more on ideological rather than regional perspectives.

At the final hour, 11 Republicans and Democrats voted against the 557-page package: Republicans Bob Goodlatte of Virginia, Tim Huelskamp of Kansas, Marlin Stutzman of Indiana, and Bob Gibbs of Ohio, as well as Democrats Joe Baca of California, David Scott of Georgia, Chellie Pingree of Maine, Marcia Fudge of Ohio, Terri Sewell of Alabama, Joe Courtney of Connecticut and Jim McGovern of Massachusetts.

Rep. Bob Gibbs

The bill, known as the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act (FARRM), maintained crop insurance as the primary risk management tool for farmers and ranchers while setting up the new Price Loss Coverage program that would pay when prices dropped below an established target.

The bill also contained provisions for Revenue Loss Coverage (RLC), similar to the Senate’s ARC, but FARRM’s PLC and RLC apply to planted acres up to total base acres on a farm. (For a comparison of PLC and RLC, see this FarmDoc analysis.)

In a press statement, Chairman Lucas and ranking member Collin Peterson called FARRM a “bipartisan bill that saves taxpayers billions, reduces the nation’s deficit and repeals outdated policies while reforming, streamlining and consolidating others.” The measure would cut USDA spending by $35 billion over 10 years, $12 billion more than the Senate version. Almost all of the additional cuts came from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, commonly called food stamps.

Raun and her USA Rice Producers were very happy with the outcome, in part because “it recognizes that you can’t have a one-size-fits-all program for all regions and crops.”

American Soybean Association’s President Steve Wellman noted that, “we remain concerned about planting distortions that could occur under a coupled target price program such as that contained in the House bill.” He said ASA’s key priority has been to develop programs that help farmers manage risk while complementing crop insurance and avoiding planting distortions.

National Corn Growers Association President Garry Niemeyer said his organization was disappointed that the House version of the farm bill “does not include a more viable market-oriented risk management program,” but urged the process to move forward.

Lucas offered an all-too familiar refrain to corn growers who criticized his version of the farm bill.

“You got yours (price supports) in the RFS (Renewable Fuel Standard),” Lucas told farmer leaders. “I’m going to make sure others get theirs…” recalled a former grower who was involved in discussions.

Ultimately, GOP leaders decided – for a variety of reasons that we’ve chronicled in Part One of this series – to not bring the House Agriculture Committee’s version up on the House floor. But even though the bill was destined to die in the House that year, the regional commodity disputes did not.

Southern game changer

The farm bill died in the 112th Congress, but Southern farm groups who had been worried about Roberts’ influence on the Senate Agriculture Committee had a new reason to cheer on Jan. 3, 2013.

Unable to stay on as ranking member of the powerful Appropriations Committee, Thad Cochran asserted his seniority over Roberts and was selected to take over as ranking GOP member of the Agriculture Committee. The senator had previously served as committee chairman from 2003 to 2005. In his new role, he and his staff planned to make sure that Southern interests were well-represented in future farm bill debates.

The committee released a new, 1,102-page farm bill draft in early May 2013 – largely including many of the previous year’s changes, but with several changes that reflected Cochran’s influence

Stabenow noted that, with key changes in latest mark, passing the farm bill would yield a total of $23 billion in cuts to agriculture programs – the same level as the previous year’s effort.

As expected, direct payments, the Average Crop Revenue Election Program and the Supplemental Revenue Assistance Program were all eliminated.

The Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) program, which was introduced in the Senate mark, remained. But in order to trim costs, the price band was set at a slightly lower range of payment (88 percent instead of 89 percent) and prices were to be calculated on a 12-month time frame, rather than the first five months of the marketing year. The measure included the Supplemental Coverage Option, whereby producers could purchase a policy on top of their individual crop insurance coverage to cover all or part of a producer's deductible.

However, the bill included several new provisions – long sought by cotton, rice and peanut interests – who had maintained that some of the traditional forms of risk management don’t work for them like they do in the Midwest.

For example, in addition to a revenue coverage program that was the centerpiece of the Senate Ag Committee’s commodity title in the previous year, the draft called for a new “Adverse Market Payment,” or AMP program, based on making payments when prices drop below reference prices.

Basically, it’s a counter-cyclical program (CCP) with enhanced rates for rice and peanuts, while the target prices established in the 2008 farm bill remain the same for all other commodities.

The reference price for rice was set at $13.30/cwt, up from the previous target price of $10.50/cwt. And the peanut target price was increased from $495/ton to $523.77/ton. Rice and peanut producers would be able to update their yields, generating potentially even more payments. Peanut producers would also be able to update their base acres.

Like the previous year, a new Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) for producers of upland cotton would also be part of the package with a few minor differences.

But it was the new AMP program that generated a lot of Southern smiles. The inclusion of AMP “is indicative of new ranking member Thad Cochran’s influence,” noted Alabama Farmers Federation National Legislative Programs Director Mitt Walker after the bill was released.

Even before the massive “Agricultural Reform, Food and Jobs Act of 2013” bill was officially released, Midwestern senators were already buzzing about the proposed new programs for rice and peanuts They realized the importance of getting Southern votes on the floor if the bill was going to pass again, but that it might work to remove other commodities from the AMP program.

Although similar in concept, the AMP was not exactly the same as the House Agriculture Committee’s Price Loss Coverage (PLC) in their version of the 2012 farm bill. For example, the PLC pays on planted acres up to total base on the farm; it includes reference price increases and yield updates for all commodities. In the House version, corn and beans would get a 38 percent increase over the 2008 levels. In addition, no special base acre accommodations would need to be made in PLC because the existing total base on a farm simply serves as a cap on total payments.

The 2013 chairman’s mark also included the same limitation on premium subsidy based on average adjusted gross income (AGI) as last year’s bill. Beginning with the 2014 reinsurance year, the provision would reduce the federal payment of the crop insurance premium by 15 percent for farm businesses with AGIs above $750,000.

On May 14, 2013, the Senate Ag Committee marked up the newest version of the farm bill. The markup was perhaps the most public discussion of the regional and philosophical rifts that had been bubbling up over the already torturous course of the news farm bill.

Chambliss described the package as a “balanced approach” versus the prior year’s bill. But Midwestern corn and soybean interests wanted more changes.

Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., offered an amendment that would limit the AMP program to only rice and peanuts. He described the AMP program as “a 20th century Commodity Title program for 21st century production agriculture (which) offers only minimal reforms.”

Thune pointed out that “AMP leaves target prices, now called reference prices, the same for all commodity crops, the same as they were in the 2008 farm bill, but does substantially increase rice and peanut target prices from the 2008 farm bill levels. Under AMP the rice reference price is $13.30 per hundredweight and the peanut reference price is $523.77. Also, under the AMP provisions in the chairman’s mark peanut bases and yields are allowed to be updated and only the rice yields are allowed to be updated. Rice bases are kept at the 2008 farm bill levels because rice has been under-planted for the past five years,” according to a FarmPolicy.com unofficial transcript of the committee markup.

Roberts agreed, noting that “this is not a reform bill. This is a rearview mirror bill.”

Sen. Mike Johanns, R-Neb., suggested that the program would be subject to a World Trade Organization challenge, similar to a Brazilian cotton case.

But they didn’t have the votes to win on Thune’s amendment and it was defeated by a voice vote.

Later that day, the farm bill was approved 15-5 by the Senate Agriculture Committee with a much different mix of votes than in 2011. This time, it was three Midwestern Republicans, Roberts, Thune and Johanns, who opposed the bill, along with Mitch McConnell and one Democrat, Kristin Gillibrand.

Chairman Stabenow had lost some of her strongest Midwestern advocates, but she gained Southern support that could presumably pave the way for compromise with House Agriculture Committee Chairman Lucas.

But that didn’t stop the three Midwestern senators from trying to modify the bill. When the bill was considered on the Senate floor in early June, Thune offered a similar amendment to focus AMP only on rice and peanuts. Once again, he was defeated.

The Senate approved its five-year farm bill (S. 954) on June 10, 2013, with a strong bipartisan 66-27 vote.

Eighteen Republican senators joined 46 Democrats and two Independents in approving the bill.

Two Democrats – Jack Reed, D-R.I., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I. – joined 25 Republicans in voting against the bill. The two Democrats likely broke ranks due to objections over proposed cuts to SNAP.

Committee ranking member Cochran applauded passage of the bill.

“The Senate has produced a farm bill that meets the needs of those involved in agriculture production and the consumers of the crops produced by American farmers and ranchers,” Cochran said. “American agriculture producers deserve the certainty that comes with a strong five-year farm bill. I’m pleased that we’ve come up with a bill that will meet that need.”

In voting against the 2013 farm bill, Roberts said the legislation was “a return to trade and market distorting policies of the past, does not represent reforms achieved in last year’s Senate passed bill and does not cut enough wasteful spending.”

On the House side, the farm bill was once again advancing in committee. Yet, some of the same arguments were still surfacing.

The bill was approved by 36-10 in the House Ag Committee on May 16, 2013. It was largely similar to the bill passed by the committee in the previous year by a 35-11 margin, with larger cuts in the nutrition title and minor changes in farm safety net programs.

“No one on this committee is going to like everything in this bill,” Lucas noted. “But farmers, ranchers and the American taxpayers are counting on us to pass a farm bill.”

Rep. Bob Gibbs, one of the 11 who voted “no” on the bill, called the commodity title “drastically unfair to Ohio farmers” because target prices were set so high for certain crops.

The full House finally took up the farm bill debate on June 19. Most of the focus was on finding 218 votes to secure final passage and start conference with the Senate. With over 100 amendments, there were plenty of ways the bill could once again be derailed. For Southerners, Amendment Two – offered by Gibbs and Wisconsin’s Ron Kind – demanded their attention and opposition.

The Gibbs amendment -- largely supported by corn and soybean interests and ruled in order by the Rules Committee - would set target or “reference” prices for all crops at 55 percent of the five-year rolling Olympic average. He argued that the change will make the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) option more market-oriented.

Keeping your eye on farm bill news? We’re covering it and lots of other ag and rural policy news. You won’t miss a beat if you sign up today for a four-week free trial Agri-Pulse subscription.

It was considered one of the biggest threats to the commodity title that Lucas had carefully crafted with the support of many Southern farm groups. And Lucas was so steamed up over the fact that the Rules Committee had allowed the Gibbs amendment to be considered that he asked House Speaker John Boehner to intervene.

Asked why the Gibbs amendment was withdrawn, Lucas carefully avoided any specifics.

“Let’s just say Mr. Gibbs is a wise and practical member. He knows that ultimately the final language will be put together in the conference committee. He understands maintaining a good rapport to still be a part of the process…. which is better than making the chairman mad.”

But a clearly frustrated Gibbs – who believed the PLC program was not good farm or fiscal policy – did not want to reveal details of the conversation when Agri-Pulse caught up with him during the farm bill debate. Instead, he offered this statement:

“I worked with the Speaker’s office throughout this process. As you know, this is just one step and we still have two more steps after a farm bill passes the House,” Gibbs noted. “The withdrawal of my amendment was only decided after an agreement by the chairman to work with the growing number of Republicans and Democrats that support changing the PLC program. You will see changes to target prices before this is all over, and everything I’ve done, and will do, has been directed at passing a long-term, equitable and market-oriented farm bill.”

After the amendment was withdrawn, Lucas promised to work with Gibbs in the conference committee to see enacted an “equitable and market-oriented farm bill”. But leaders from the American Soybean Association, National Corn Growers Association, National Sunflower Association and U.S. Canola Association didn’t waste any time hiding their disappointment.

Gibbs was never named to the conference committee, but those arguing for his amendment didn’t give up. Increasingly, corn and soybean growers relied on Chairman Stabenow to provide the type of "ballance" they wanted in the bill.

Ultimately, the farm bill failed in the House by 195-234 – not because of regional divides but because of a mix of political factors driving a wedge between fiscal conservatives and more moderate factions of the GOP. But regional differences on the commodity title – including ARC, PLC, payment limits, planted versus base and more.

After that time, it took an almost herculean effort to finally pass a bill in the House – albeit without the nutrition title, conference with the Senate and then gain approvals from both chambers in a fashion that President Obama would be willing to sign on Feb. 7, 2014. The final commodity title package includes the ARC program favored by corn and soybean growers - available at the farm and county level (rather than crop reporting district) and the PLC program favored by southerners. Growers would have the option to pick one of these options. Payments would be calculated on base, rather than planted acres.

In retrospect, regional fights weren’t the only reason for delay, but farm bill veterans say the lack of unity among commodity groups didn’t help improve an already complicated and controversial farm bill debate.

In retrospect, regional fights weren’t the only reason for delay, but farm bill veterans say the lack of unity among commodity groups didn’t help improve an already complicated and controversial farm bill debate.

“We didn’t need a circular firing squad showing up, when we already had enough external bullets flying our way,” recalled a source who was involved with the negotiations.

So as farmers and ranchers look ahead to the 2018 farm bill, it’s not surprising that farm organization leaders have already been meeting for months, trying to find areas of agreement on the commodity title and other provisions.

“It’s not likely that regional divisions will cease to exist, but perhaps they can be minimized,” noted one of the leaders involved in those discussions.

Failure to work together could mean that risk management tools like crop insurance – where there is already strong support from across the country – could also be targeted.

Mike Day, the chairman of National Crop Insurance Services, said that “policy critics will be working overtime in their efforts to misinform new policy makers.”

Day expects crop insurance opponents to single out recent years – when insurance indemnities were lower – without acknowledging the crop insurance industry’s performance during the flooding, droughts and price declines that marked 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

“It will be up to us to remind Congress that the good years help balance the bad,” he said. “Overhauling a program to make it less economically viable ultimately hurts farmers, who need risk management tools to produce food and fiber for a growing world population.”

“I think our biggest challenge is going to be, how to be unified when we go forward with a farm bill,” emphasized American Farm Bureau President Zippy Duvall during his organization’s annual meeting earlier this year. “We’ve got to find common ground in that to make sure that everybody has that safety net that covers them.”

#30

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com