An insurance policy created to help diversified operations, specialty crop growers and small farms better manage their risk has slipped in popularity over the past two years, but advocates say a series of changes USDA is making in the program could reverse the decline.

Some 2,216 Whole Farm Revenue Protection policies have been sold this year, down from its peak sales year of 2,836 plans in 2017. Some 2,537 policies were sold in 2018.

In select states, the decline has been even more pronounced. Just 55 policies were sold in Montana this year, down from 140 in 2017, and there were similarly sharp drops in the Dakotas. In Tennessee, sales dropped from 54 to 19 over the two years.

There are different theories for the decline, but the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, one of the program’s leading champions, believes the drop is due to rules that have hurt farmers who have had one or two poor yields. The 2018 farm bill directed USDA to consider a number of modifications to the program, including ways to soften the impact of disasters on WFRP coverage levels, and the Federal Crop Insurance Corp. board last month approved several rule changes.

Doug Crabtree, an organic farmer in north central Montana, says he buys WFRP coverage because traditional revenue insurance policies aren’t available for many of the crops he grows such as black lentils and purple barley. But because of a devastating drought in 2017 - he lost 90% of his expected revenue — his WFRP coverage has dropped significantly.

WFRP policies allow producers to insure a portion of their revenue based on the average that they have received for the previous five years.

He still bought a policy this year despite the reduced coverage, but he’s only insured for roughly $400,000 of his $1 million in projected revenue, he said.

“Right now, under the rules as they are currently written if you have even one disaster year … it drastically reduces the effective safety net, or the amount of your revenue that you can insure,” he said.

USDA Chief Economist Rob Johansson

He went on, “Pretty much everything about the whole farm works well for us but this one idea that there is no way under the current rules to smooth out or to take away the impact of a disaster year if it hits within” the five-year period.

Among the rules changes the FCIC board approved is a tweak to drop the lowest revenue year from a producers’ five-year history. Another change would limit how much a farmers’ revenue history could fall in any one year to 60%. A third change made to how coverage levels are calculated would mean that revenue for the latest year could not fall more than 10% from the previous year.

Also, starting in 2020, disaster payments will no longer be counted in a farm's revenue for purpose of calculating potential indemnities.

Rob Johansson, USDA’s chief economist and chairman of the FCIC board, says the changes to how a farm's revenue history is calculated, coupled with the improvements for livestock producers and nurseries, should make the policies more attractive. “We’re hoping this will turn it around,” he said.

FCIC agreed to loosen limits for insuring livestock and nursery revenue. Under current rules, farms are ineligible for WFRP if they have more than $1 million in revenue from livestock or nursery production or if more than 35% of their revenue is from those sources. Under the new rules, farms can insure up to $2 million in revenue from those sources, and operations will still be eligible for WFRP even if that revenue exceeds the insurable limit.

Other changes for 2020: If there is another round of Market Facilitation Program payments next year those won't be counted in a farm's revenue either. This year, they will be. And farms will be allowed to collect indemnities from both WFRP and the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, or NAP.

The net effect of the modifications in how farm revenue is calculated after disasters will make WFRP more similar to other forms of crop insurance, according to NSAC.

“The bad years were catching up with lots of producers and renewing a WFRP policy left them grossly underinsured and it was no longer worth the cost to farmers who had major drought (or wet) years recently,” said Ferd Hoefner, senior strategic adviser for NSAC.

Another theory about the drop in WFRP policies is that some producers are finding traditional revenue protection policies that meet their needs. Recent improvements, for example, have allowed policies for organic production to more closely reflect organic prices, said Tara Smith, vice president of federal affairs for the Crop Insurance and Reinsurance Bureau Inc.

“I hope it [the decline in WFRP policies] is because folks are finding things that work better for them. Certainly, USDA has worked to do some streamlining of whole farm and make some improvements there as well,” she said.

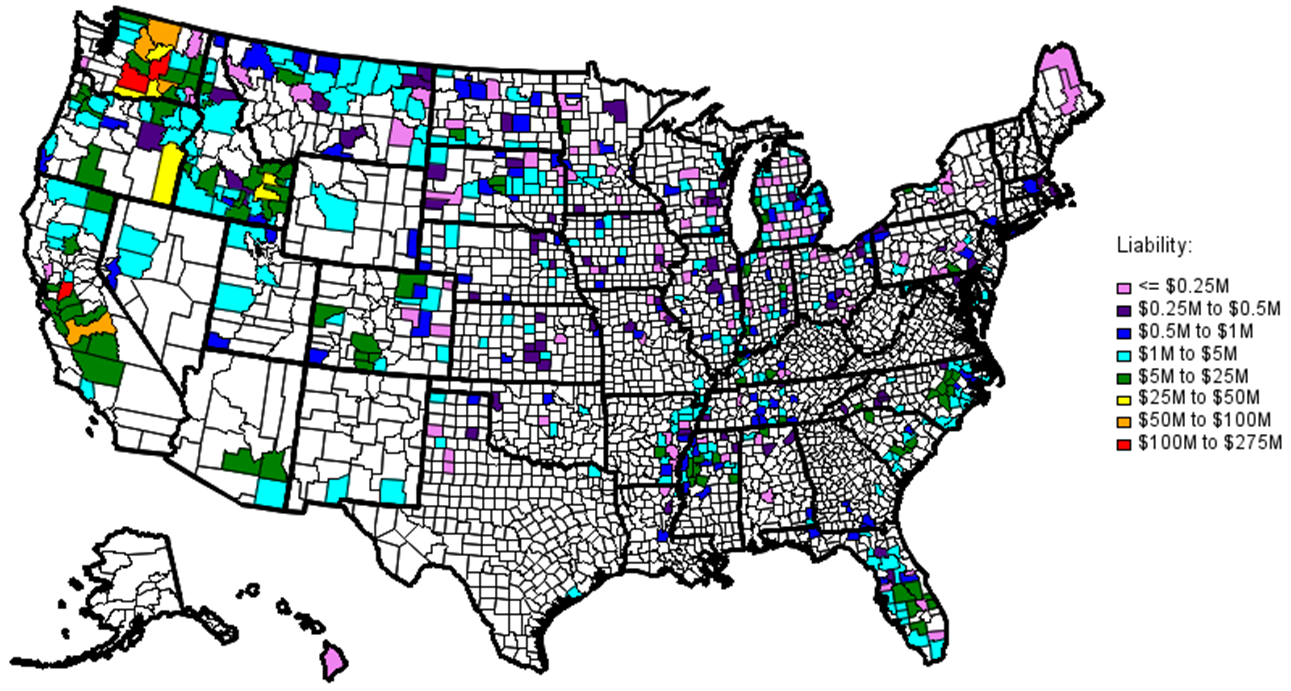

Participation in the program is still twice what it was in 2015, the program's first year, when 1,128 WFRP policies were sold. The program's total liability grew from $1.15 billion in 2015 to $2.84 billion in 2017 before falling back to $2.14 billion this year. WFRP was authorized by the 2014 farm bill to combine and build on two pilot programs known Adjusted Gross Revenue and Adjusted Gross Revenue-Lite.

A few states continue to see growth in WFRP participation, including California and Florida. Some 191 policies were sold in California this year, up from 172 in 2017. The number of policies in Florida has risen from 77 in 2017 to 125. Washington state remains the top market for WFRP, with 769 policies, compared to 804 two years ago.

NSAC still has concerns about the program despite the changes FCIC approved. The group doesn’t think there are enough agents in many parts of the country who promote the policies to producers. The Senate’s version of the 2018 farm bill included special incentives for marketing WFRP policies but the provision was dropped from the legislation during negotiations with the House.

Separate from the changes in calculating WFRP coverage, the FCIC board also made industrial hemp eligible for the insurance program starting in 2020, a requirement of a provision that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell wrote into a supplemental appropriations bill enacted in June.

There are some limitations for including hemp in WFRP policies, however. The product will be required to have a contract for the hemp, and the crop will have to be grown under state or federal plans.

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.