California winegrape growers and vintners are trudging through a painful economic passage that farmers worldwide have tread time and again: an unforgiving market.

When production nudges supply only moderately above market demands, it can punish producers harshly.

The sin of growers was to keep doing what had worked so well, explained Jeff Bitter, president of Allied Grape Growers, which monitors California grape acreage, production and wine stocks.

“Our growth had been so consistent over two decades,” he said, describing a generally steady 3% annual growth in sales during that time. “People just became accustomed to that growth, and that’s what they planned for the future.”

Growers were planting up to about 30,000 acres of new vineyards a year and not removing enough tracts of old vines, until the bearing acreage swelled to about 590,000 in 2018 and 2019. On top of that, the highly productive Central Coast had a bumper crop in 2018, and Californians grew and crushed nearly 4.3 million tons of winegrapes.

Worse, the long growth in total wine sales stalled out, Bitter said, while wineries continued to make more wine than they could sell in recent years, adding to surplus stocks.

The 2018 crop “pushed us over the edge,” he said.

In 2019, many wineries slammed their brakes on open-market purchasing from growers and let some contracts with growers expire, leading to a plunge in winegrape prices.

Thousands of vineyard acres were left unharvested last fall, and lots of harvested grapes had no buyers. The 2019 California Grape Crush Report, released this month by USDA and the California Department of Food and Agriculture, reflects the industry’s skid: a 9% plunge in tons of grapes crushed (due in part to weather), despite little change from 2018’s record bearing acreage.

“In the wine business, you have to plan so far ahead to accommodate future demand that by the time you plant a vineyard and get it producing (an interval of five or more years), and then make wine and age it and barrel it and all that stuff, you’re talking about (many) years … to get it on the store shelf,” said Bitter, adding: “Wine is not a commodity that clears itself in the market. It hangs around and becomes inventory, (for years whenever you exceed demand)," he said.

Foreign trade challenges are contributing to growers’ pain.

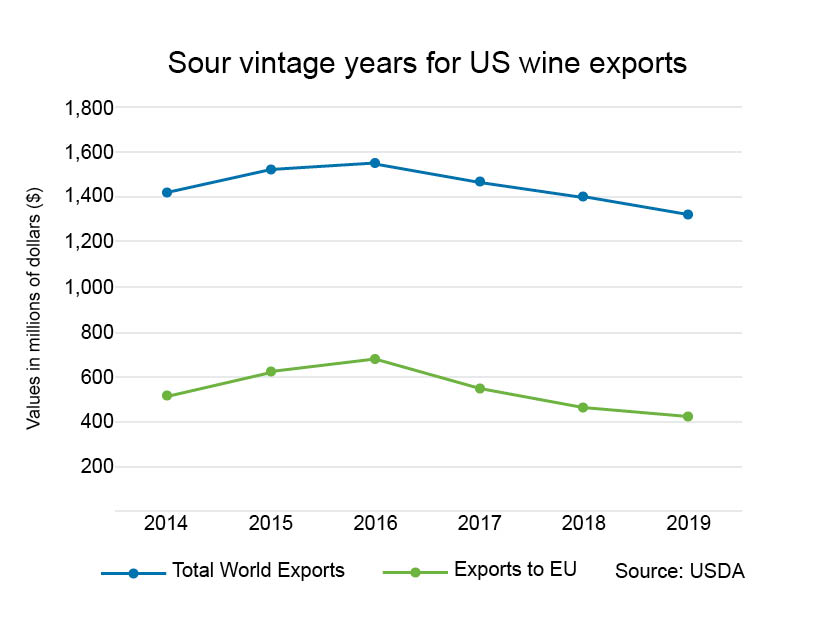

California, which accounts for 95% of U.S. wine exports, sells about 20% of production abroad most years. U.S. wine exports rose 90% from 2006 to 2016, topping $1.5 billion, USDA records show. But exports have since dropped by more than $200 million, owing essentially to an even bigger plunge of $260 million a year in sales to the European Union.

The U.S. wine exports picture is complex and some wineries are doing very well. The quality and reputation of California wine has soared so much, for example, it was reported at the recent 2020 California Wine Global Export Conference that average international prices of California’s bottled wine are now second highest globally, between prices of French (number one) and Italian bottles.

Yet sales abroad have dropped overall.

John Aguirre, Association of Winegrape Growers

“Certainly, the strong dollar is a substantial hindrance for U.S. wine (sales),” said John Aguirre, president of the Association of Winegrape Growers (AGG), explaining how it adds to California wine prices abroad.

The U.S. trade war has been choking wine sales in China, an emerging market recently for California vintners. China has retaliated against President Donald Trump’s tariff actions by bumping up its tariffs on American wine to 93% since early 2018. U.S. wine sales to China fell from $79 million in 2016 to $39 million in 2019.

Aguirre said China wasn’t the largest market, but was large and growing rapidly for California wine exports.

“So it’s very disappointing to see our exports diminishing, because we were on track to make major headway in that market," he said. "It’s a tremendous lost opportunity with respect to China.”

If export troubles aren’t enough, wine imports are also squeezing California producers. They’re up about 16% by both volume and value in the past five years, and over a third of wine Americans consume is now imported, industry researchers find.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

“The U.S. is the largest consumer market for wine and the most profitable, and that attracts a lot of attention from wine-producing competitors,” said Aguirre.

Much of the imports are low-priced bulk wine purchased by large wine companies for bottling and otherwise marketing in the U.S. He said growers in the Central Valley, who compete at the more economical end of the spectrum, have been among the first to lose sales to such imports.

“It’s very challenging to compete with Europe, Australia, Chile and Argentina in the lower-priced spectrum,” he said.

Still, the California industry is not facing disaster, despite the tough year for many producers. The 2019 average price for winegrapes, at $805 a ton, for example, is about 4% higher than the previous five-year average.

Growers have been correcting the problem.

"There are two issues,” said Bitter. “We’ve got to adjust our bearing acres for the future… But we’ve also got to work through the inventory we have now, which is at all-time-high levels. That takes a little time.”

Bitter said 30,000 to 50,000 acres need to be cut. His group's monitoring of acreage decisions by growers so far suggests a net reduction of 20,000 acres is likely, and perhaps more.

“So I don’t think we’re going to accomplish what we need to accomplish in this single year... and I think it may be a two-year effort to get our bearing acreage where it needs to be," he said. "We’re not that far off: maybe just a 5 or 7% adjustment in acres and we’ll be back into balance.”

Rob McMillan, Silicon Valley Bank

Long term, the needed correction is on the demand side, said Rob McMillan, vice president in charge of wine sector lending at Silicon Valley Bank.

McMillan, in a recent industry assessment, agreed growers must pull out vines to slash production in the short term. But he said vintners and grape growers are both “missing the mark on consumer expectations” and not competing well in the beverage market.

"(Slumping demand) hurts everybody, whether you’re a grower, a winery, a cork manufacturer, bottle supplier … (or making) labels, bags,” he said.

McMillan wanted all players in the industry “to come together and find some of the solutions," particularly in branding wine as healthy and for new consumers.

"(Grape growers and wineries) are on the side of the angels – you can’t get a more natural product than wine,” he said.

McMillan noted that the recent large sales of 2018 vintage Napa Valley Cabernet in the bulk market hinted at relief in that corner of the wine market.

“But if that leads anyone to think the pain is over – it’s not,” he said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com