Major farm states are likely to lose more influence in the U.S. House because of population shifts that are expected to result in lost seats across the Midwest as well as in Pennsylvania and New York.

The results of the 2020 Census are not expected to be released before March, but analysts expect the states losing seats to include Illinois, Ohio, Michigan and Minnesota. California also could lose at least one House seat.

"As we continue to lose members of Congress from rural America, I worry about the long-term effect it will have on agriculture,” Rep. Darrin LaHood, R-Ill., told Agri-Pulse.

State legislatures, and in some cases independent commissions, are responsible for drawing new districts based on the Census results. In most cases, the lost districts are likely to come out of rural areas.

A reapportionment study conducted by Election Data Services — a political consulting firm — using Census Bureau estimates found Texas will likely gain three congressional seats, Florida will gain two seats, and Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Carolina and Oregon would each add a single seat. Montana could gain a seat, but by only 4,714 people, according to the Election Data Services estimate.

Several farm states, California, Illinois, Ohio and Minnesota, Michigan and Pennsylvania, along with Rhode Island and West Virginia are likely to lose a seat. Under certain scenarios, it’s possible Alabama could lose one seat and New York could lose as many as two.

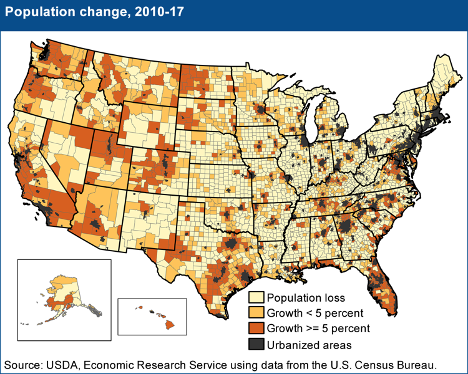

The challenge to rural political influence is that most population growth continues to be in the cities and suburbs, and new districts must be drawn to reflect that.

Lawmakers who are drawing new districts can "manipulate things a little bit on the margins" to help rural areas, but in the end it "all comes down to where people live," said Christopher Mooney, a professor of state politics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “If nobody’s living there, you’re not going to have political power.”

According to USDA's Economic Research Service, 46.1 million people lived in rural counties in July of 2016. Between 2006 and that year, annual rates of population change fell from 0.7% to below zero, before slightly increasing by 0.1% between 2016 and 2017.

In contrast, urban population rates in the United States only fell by 1 to 0.8% percent between 2006 and 2016.

Historically, the parties in control of state governments have had the opportunity to gerrymander, or manipulate, district boundaries to favor their party. However, this has been a controversial practice and has prompted states like Colorado, Michigan and Utah to create independent redistricting commissions that have the task of deciding how boundaries should be drawn.

Illinois, which currently has 18 congressional districts, is one of the states that has seen a population decline in recent years. According to population estimates from the Census Bureau, the state lost 79,487 residents between July 2019 and July 2020. The state was ranked No. 6 by the Economic Research Service in 2019 in agricultural production.

Rep. Rodney Davis, a Republican who represents Illinois’s 13th District, which spans both urban and rural areas across 14 counties in the central and southwestern parts of the state, told Agri-Pulse he worries the state's Democratic-controlled legislature will take the seat from one of Illinois’s rural districts, most of which are GOP held.

“Our congressional districts are drawn by the Democrats in Springfield and Gov. (J.B.) Pritzker has to approve that map,” Davis said. “He has said in the past that he wants to see a fair map drawn. I think our rural constituents need to make sure that their voices are heard so that he sticks by that pledge.”

LaHood, who represents the 18th District in central Illinois, shares the same concern. He believes the seat will be taken from downstate Illinois, which is largely rural.

Minnesota has been on the edge of losing a seat for decades, keeping it by only about 8,000 people in the last census. According to State Demographer Susan Brower, Minnesota hasn’t seen much population loss — even in the rural areas. The state's just been outpaced in recent years by states like Florida and Texas.

“The picture is much more one of stability, that there aren't huge population losses in many of our rural areas,” Brower said. “It's just that the population gains are concentrated in the metro areas.”

Steven Schier, a former professor of political science at Carleton College in Northfield, Ill., told Agri-Pulse that because Minnesota’s legislative power is split between both parties, the Minnesota State Supreme Court will likely end up with the responsibility of redrawing the district boundaries.

“We are the only state legislature in the country with divided control: Republicans in the Senate and Democrats in the House,” Schier said. “So they're not going to agree on a law, on a redistricting plan. It will go to the state courts and they will draw it.”

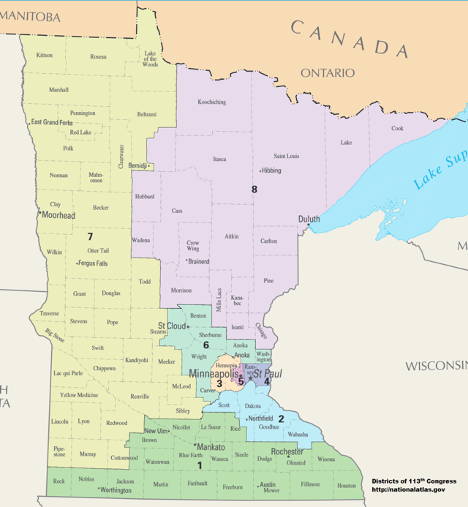

Schier believes that because of this, it is likely the state's remaining, largely rural House districts will be redrawn to cut deeper into the districts surrounding Minneapolis and St. Paul to capture some of that region's population. First-term GOP Rep. Michelle Fischbach, who defeated long-time Democrat Collin Peterson in the 7th district last year, could be one of the most vulnerable members.

“They will be redrawn in a way to draw on some of that population,” Schier said. “That's going to make all of those districts less rural in their voting profile than they were before.”

Schier also noted that larger districts require their representatives to cover more ground.

Minnesota's current congressional districts

“You can expect that these rural districts are going to cover even more counties and more geographical areas,” he said. “That requires a lot of traveling on rural roads and in small planes.”

California, which currently has 55 districts, is expected to lose a seat for the first time in the state's history.

“The state of California, since it became a state in 1849, has always gained congressional seats,” said Kimball Brace, president of Election Data Services. “This time, what we’re seeing in the data is a strong probability that they, in the first time in their state history, will lose a congressional seat.”

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse West.

Mike Zimmerman, political affairs manager for the California Farm Bureau Federation, said he is not sure which of California’s districts will go, and he likely won’t have any idea until the Census results are released. He said the California Farm Bureau is preparing to keep agriculture in the redistricting discussions.

“We've been talking with our members and our leadership over the last two years now, preparing for this and making sure that when the commission does hold public hearings and when they release initial lines, agriculture has a voice in making sure that we're represented,” Zimmerman said. “The way that we're represented in that process is by talking about communities of interests and why agriculture districts should remain whole districts.”

Based on the latest projections, Texas will likely gain three seats, giving it 39. The state grew from about 25 million people in 2010 to over 28 million in 2019, according to the Texas Demographic Center.

But even though the state will gain seats rural voters could still lose clout. According to a report by Texas Monthly magazine, Republican state lawmakers may combine two of the three large agricultural districts in west Texas and shore up Republican districts to the east. The 13th District, which includes Amarillo and the Panhandle, and the 19th District, which includes Lubbock and Abilene, no longer have enough population on their own. The districts are represented by freshman Ronny Jackson and Jodey Arrington respectively.

Laramie Adams, the national legislative director for the Texas Farm Bureau, said the impact of the new districts on rural areas depends on where they will be added.

“As you see the populations grow, and as these districts change, I think we’re going to have to be working to engage people that have an appreciation for agriculture,” Adams said. “It’s going to change the dynamics of elections and who the constituents are.”

Billy Howe, the associate director of government affairs at the Texas Farm Bureau, believes new districts could be added in the Houston area, along the I-35 corridor between Dallas and San Antonio, and in the Rio Grande Valley. Those are regions that have seen the highest levels of population growth in recent years.

“Unlike some of the other states, from an ag [and] rural standpoint, we are fortunate enough that the growth in our state has caused us to gain seats each redistricting, and that has helped to mitigate a little bit of the loss of ag [and] rural representation,” he said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.