(Editor’s note: Rabobank’s Roland Fumasi spoke at the Agri-Pulse Food & Ag Policy Summit on Monday but we also captured some of his comments during an extended conversation about this year’s drought impact, industry consolidation and other changes ahead for California agriculture.)

With drought conditions worsening in many parts of California and more water restrictions, farmers will likely idle between 600,000 to 800,000 acres this year, says Roland Fumasi, EVP & North American Regional Head, RaboResearch Food & Agribusiness. That does not include the potential impacts of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

While much of the western U.S. is experiencing drought conditions, California is one of the hardest hit. As of June 22, 2021, 100% of the state is experiencing some degree of drought. About 33% of the state has been categorized under exceptional drought, the most intense drought classification. But water access varies greatly by region of the state.

During the last major drought, which ended in 2016, Fumasi said there were about 600,000 acres that didn’t get planted. The number could be a little worse this year because soil recovery from the last drought has limited water availability even more, added the California native.

When it comes to SGMA, Fumasi says “we are still in the early stages.” But some of the water districts are already starting to implement higher costs for groundwater pumping or higher fees associated with trying to conserve groundwater — even though the SGMA plans have not yet been approved by the state.

“We're going to see a lot more groundwater pumping this year than we would otherwise, just to keep crops alive. But that's going to come at a higher cost.”

As a result, “we're going to see less water find its way to thirstier crops like alfalfa, cotton and rice. Some farmers in the Sacramento Valley are going to sell water and plant less rice,” Fumasi said.

The Nasdaq Veles Water Index, which tracks the spot rate of surface water per acre-foot in California, dropped down to $480/acre-foot last winter and as of July 9, was about $841/acre-foot — about a 75% increase.

Fumasi says there'll be growers who will be paying more for water to keep permanent crops alive — whether that's blueberries or pistachios, and almonds in some cases. However, he points to a weak almond market that may complicate decision-making.

“We’ve had a really weak almond market where, if you consider cash costs as well as amortized costs, have been below breakeven, and by my projections are likely to remain relatively weak for the next season, as well.”

Fumasi says we will likely see almonds “being pushed out at a more aggressive rate. And 6-9 months from now, you are really going to see a heightened pace of older almond trees coming out.”

The other challenge with almonds is that they are very sensitive to salinity, he adds. “If you have to rely on groundwater and you don't have enough surface water to blend to reduce the salinity of that groundwater, almond yields are challenged. If you’ve got weak prices and pile weaker yields on top of that, that's a disaster.

However, he says that’s not the case with pistachios, which are more of a salt-tolerant tree. Pistachio markets have held up well and were very profitable over the last 12 months. “You might see people start to favor that crop, because of those two aspects. But that's not to say there won't be some pistachios come out if folks just can't get water,” he adds.

The coastal crops in the Salinas Valley, the leafy greens, the berries and some peppers rely heavily on groundwater, but their groundwater situation is a little different than the Central Valley. They rely heavily on the Salinas River, which is an underground flowing river, rather than a stable aquifer like in the Central Valley.

Will flows be impacted by the dry weather? “Absolutely, but our reports from our clients so far report they're still going to have reliable groundwater. That river runs a pretty long stretch so the northern part sounds like it's going to be OK. As you move south and other little pockets on the coast, you start to run into trickier groundwater situations. So, there's going to be some acreage that is reduced.”

But Fumasi says there’s a different scenario in the desert region. “The Imperial Valley tends to rely on Colorado River water, so growers there usually have the most robust water access of any place in California. But given what’s happened, not just now but after that last five-year drought, there has been a lot of contention on Colorado River rights.

“People are really battling for water there, but the Imperial Irrigation District, which would be the biggest irrigation district in the California desert, is still expecting, anywhere from about 80% to 100% flows from the Colorado River, depending on which specific canal is used.

“When you go up to the north coast and the major wine growing regions, they've had some major water cutbacks," he added. "We could see an impact on grapes, to some extent. In certain pockets, even in the Sacramento Valley, it just depends on where you are. There's a big part of the Sacramento Valley that has extremely reliable groundwater and they're going to be fine."

Fumasi says one of the brightest spots of the federal water system in California is the Friant division, which relies on the Friant/Kern canal.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse West

“Where I live in the southern San Joaquin Valley, that allocation still stands at 20%. Not a high allocation, but generally speaking that's typically the segment of the federal system that at least gets the highest allocation down here in the San Joaquin Valley. So, they'll be able to combine some groundwater pumping with some surface water availability.”

Regardless of the current drought and water cutbacks, Fumasi says he’s still sees California as a specialty crop production powerhouse well into the future, albeit one that will look different.

“As I look forward, yes, we will we have less acreage that’s irrigated in California in 5-15 years from now,” Fumasi says. “You'll continue to see some consolidation, which we've seen big time over the last 10-15 years. You'll continue to see farms that have economies of scale buy some of the smaller players.”

Other highlights from Fumasi:

- "Although it’s counterintuitive in some ways, we'll continue to see the water that we do have available go to permanent crops — even though there's greater risk in that because you've got to water permanent crops. That has been the trend, even in the last drought."

- "We'll continue to see genetic improvements, as well as creative management practices, whether it's for annual fruits and vegetables or trees and vines that will continue to drive higher yields."

- "There's going to be winners and losers — given SGMA. For example, the land values in the areas that are not covered by an irrigation district and rely 100% on groundwater. Those land values have really deteriorated over the last 3-4 years, because they have no surface water availability to recharge the groundwater. And without that tool, it’s just too risky given SGMA. Those in California that have the most robust water rights and are in the most robust water districts are going to continue to be more valuable."

-

“Any policy that is implemented that challenges California’s ability to produce food necessarily has a negative impact on billions — with a ‘b’ — of consumers globally, all else remaining constant.”

- "There’s a reason that 80% of all the leafy greens come from California because it's just got an ideal climate, but when you consider access to water, the need for a shorter value chain, increased shelf life — all these things fuel that protected culture trend, because it extends growing seasons outside of California."

- "Traditional greenhouses have been all about tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, plus high-value leafy greens and some specialty lettuces. But now, we're starting to see strawberries move in that (protected culture) direction with Driscoll’s and Plenty, working on true, indoor farming under LED lighting — not a greenhouse. We know that Berry World from Europe has partnered up with Mastronardi, based in Canada, to experiment with growing more strawberries in greenhouses, so there’s movement in that direction."

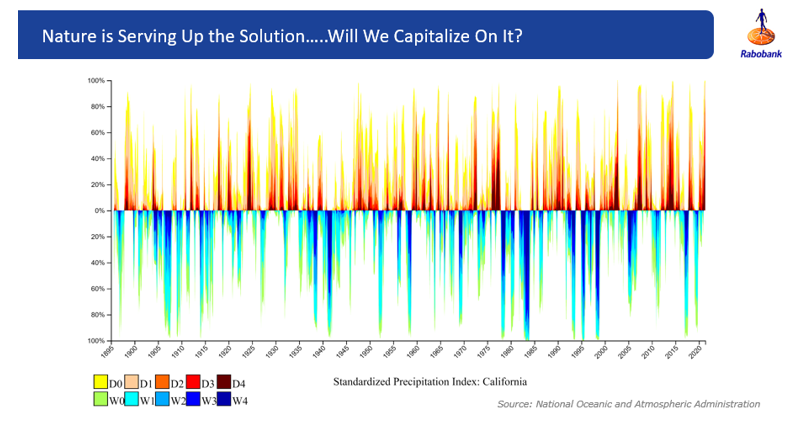

- "The precipitation index in California over the last 125 years shows that, over the last decade, the dryness has intensified a bit, and you also see that the wet years have intensified a bit. The wet years have actually gotten more extreme than the dry years. We need more ability in California to capture and store water during these wet periods so that we can get through the dry periods. That is the most logical solution to the water challenges."

For more news go to: Agri-Pulse.com