While the Inflation Reduction Act increases funding for existing agricultural conservation projects, its investment in renewable energy has the potential to also help expand indoor agriculture.

Currently, startup costs for indoor agriculture are far greater than even the costs of land and equipment that often are barriers to entry for traditional farming, says Ricky Volpe, an agribusiness professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

“There's high upfront costs that then get ameliorated over time,” he says, “based on higher production. But that takes time, for that investment to be recouped.”

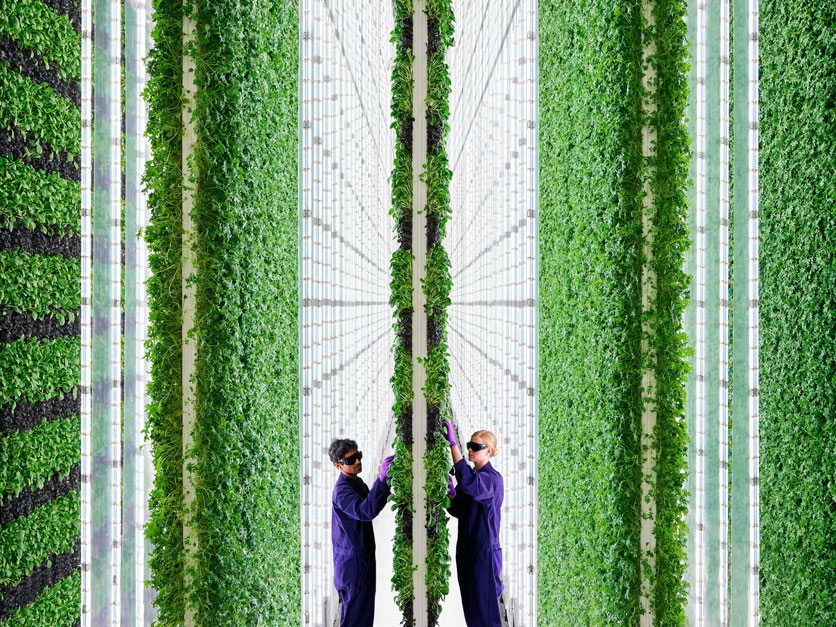

And, Volpe says, even once that capital investment is made, indoor agriculture consumes copious amounts of energy, one of the biggest costs of operation. He says vertical farming, where plants sit on multiple tiers within a building, is one example of controlled indoor agriculture.

“There's no question that vertical farming is more energy intensive than outdoor, uncovered, sort of ‘regular ol' row’ farming,” he says. That’s because without natural sunlight, an indoor growing structure needs a source of light that can provide plants what they need. “Turns out, that's not easy to do in terms of either the energy intensiveness or the technological implementation that’s needed to get it done.”

Readily available renewable energy, especially if it eventually brings lower rates, could change that math.

“The main issue is that we need to create renewable energy efficiently, and it has to be highly storable,” Volpe says.

Ricky Volpe, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

Ricky Volpe, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

That’s where new federal investments could help. The White House expects the Inflation Reduction Act will fund 950 million solar panels and 2,300 grid-scale battery plants by 2030.

“The Inflation Reduction Act, to the extent that it's spurring investment on these technologies, on this sort of widespread expansion of our capability to power the country using renewables, is absolutely good news in terms of the future of the growth of vertical farming,” Volpe says.

For now, leafy greens and herbs are leading the move indoors. And while Volpe says California stands to gain a lot from indoor agriculture, especially as both water and labor grow more scarce and Silicon Valley’s innovation and venture capital put more focus on food production, the promise of indoor farming extends to other parts of the country.

On the East Coast, companies such as Bowery Farming are installing facilities near major urban areas to help fill the demand for leafy greens, strawberries and commodities. Bowery is counting on the new IRA incentives to increase the availability of renewable power in areas where it wants to expand; its existing facilities — located in New Jersey and Maryland — already use hydropower or renewable electricity.

“The future of agriculture must be powered by renewable energy if we are going to meet our global climate commitments,” the company said in a statement to Agri-Pulse.

“As the largest indoor vertical farming company in the U.S., Bowery powers our network of smart indoor farms with 100% low impact renewable energy and is committed to continuing to do so as we launch new farms in Georgia and Texas next year. The provisions in the IRA will be critical in expanding the production, availability and affordability of renewable energy to ensure a reliable supply that meets the growing demand.”

Gary Hilberg, the chief sustainability officer at Montana-based Local Bounti, says the environmental footprint of indoor agriculture will simultaneously improve as the nation shifts to renewable energy.

“Our focus in this area will be increasing the yield in our facility in order to get more out for the energy in,” he said. That calculation — of yield out per unit of energy in — will become greener as the energy input comes increasingly from non-fossil fuel sources.

Hilberg said it's important to look at both electricity, which provides the lights plants need, and what the source of heating or cooling is. Right now, that's most often natural gas. But he said as other federal incentives may push companies to use more heat pumps (an energy-efficient technology that can heat or cool as needed), the need for natural gas should come down. Pumps also use electricity, but Hilberg said indoor growers can work with their electric utility to get the best rates possible.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse!

While it could be years before carbon-neutral electricity is meaningfully cheaper than it is today, he says the Inflation Reduction Act “will be positive for those growers who understand their energy uses and profiles.”

For example, he said an indoor farm could turn on the lights an hour or two later in the day to avoid a peak demand time. And plants are used to fluctuations in light and temperature, so interruptions aren't catastrophic as they can be in other industries with high electricity demand, such as server farms. “We have a lot of flexibility.”

The big energy savings for indoor agriculture, though, Hilberg said, can come from the reduced need for transportation. That's why they build near where they plan to sell. It's also part of the reason Plenty, a Silicon Valley indoor ag company, and berry giant Driscoll's recently announced a major investment in Virginia. The companies plan to grow Driscoll's strawberries on a 120-acre “campus” near Richmond.

“Through more than a decade of investment in research and development, Plenty has cracked the code on a scalable platform that makes indoor farming increasingly economical,” Arama Kukutai, CEO of Plenty, said in a statement. “That innovation makes it possible for us to grow a wide variety of crops with a fraction of the land and up to 350 times more yield per acre than conventional farms.”

Driscoll's strawberries grown indoors using Plenty technology. (courtesy of Plenty)

Driscoll's strawberries grown indoors using Plenty technology. (courtesy of Plenty)

Plenty's six-year, $300 million investment in Virginia is expected to eventually grow leafy greens and tomatoes in addition to berries. (The company says it will create 300 full-time jobs, too.) The company does not yet have an estimate on the energy costs to operate the campus, but in a statement to Agri-Pulse said, “the state's commitment to 100% carbon-free electricity and the progress Dominion Energy is making toward that were another element that made Virginia an ideal location for us to build.”

I “What’s unique about Plenty farms is that they can grow multiple crops on the same site using the shared infrastructure,” the company noted in its statement.

Volpe also said there are national retailers investing in indoor production. These systems, he said, can be vertical in the sense of growers producing specifically for a certain buyer and also in the sense of tiered growing platforms.

“It makes tons of sense,” he says, for large retailers “to make some pretty significant investments” in sustainably-powered vertical agriculture. Some retailers, including Walmart and Albertson’s, already “are doing some really, really high profile, innovative things in the realm of renewable energies.” Solar panels in parking lots, for example, help reduce the store's carbon footprint and they could be used as a power source for indoor growing.

With its lack of pests and weeds and insulation from weather extremes, indoor agriculture offers an expansion of potential growing locations. But Volpe points out a temperate climate will still have an advantage.

All these factors suggest a likely increase in the production of fruits and vegetables outside of the powerhouse growing regions of California, he added.

“Indoor, controlled agriculture is one of the ways that I think we're going to continue to see specialty crop production in the United States migrate away from California,” Volpe says.

However, he added it won’t be a mass exodus and it’s not imminent.

“It's just simply not sustainable to maintain the share of specialty crop production in California that's been going on historically,” he says.

Recent research shows California is in a megadrought unseen since at least the 1500s and also reveals that the 20th century was anomalously wet. In the future, Volpe expects the Pacific Northwest and Canada may pick up some of the production California will be unable to support. And, he expects to see “a much bigger share of specialty crop production in the U.S. happening indoors and in controlled environments.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.