The deal that opened up grain exports from three ports in Ukraine is widely lauded as a success in bringing down global food prices, but the future of the Black Sea Grain Initiative is being threatened by Russia, and United Nations officials are scrambling to save it.

When Ukraine, Turkey, Russia and the U.N. signed off on the Black Sea Grain Initiative, they also signed off on a deal to allow the unimpeded flow of Russian fertilizer and wheat exports.

While millions of tons of Ukrainian wheat and corn are to be shipped from Odesa as part of the Initiative, Russian President Vladimir Putin is complaining that the agreement on Russian fertilizer exports is being stymied by logistics, evolving and complex European Union sanctions and other barriers.

And that is spurring the U.N. to desperately try to create pathways for Russian fertilizer into the European Union and the rest of the world as Moscow grows impatient and international concerns mount over a potential shutdown of the grain shipments.

Amir Abdulla, the U.N. coordinator for the Black Sea Grain Initiative, said at a press conference last week in New York that the U.N. knows the initiative only exists at the whim of Moscow, and its fate is tied to the second deal to allow for Russian fertilizer exports.

“The U.N. is pursuing all efforts to allow positive outcomes on Russian (fertilizer) exports to international markets,” Rebeca Grynspan, the secretary-general for the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development, told reporters at the press conference.

Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist for the StoneX Group, says he’s surprised that Russia has allowed the Black Sea Grain Initiative to go on as long as it already has.

Suderman, a speaker at the Ag Outlook Forum in Kansas City, Mo., on Monday, stressed that the Russian military continues to target the Ukrainian ag sector, bombing silos and other farming infrastructure.

“They could easily pull the plug on Black Sea shipping, there’s no question about it,” said Kip Tom, CEO of Tom Farms and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Agencies for Food and Agriculture during the Trump administration.

But U.N. officials stress they are not just trying to appease the Russians on fertilizer exports to save the Black Sea Grain Initiative and the grain flowing from the three ports in Odesa since July 22, when it was initiated.

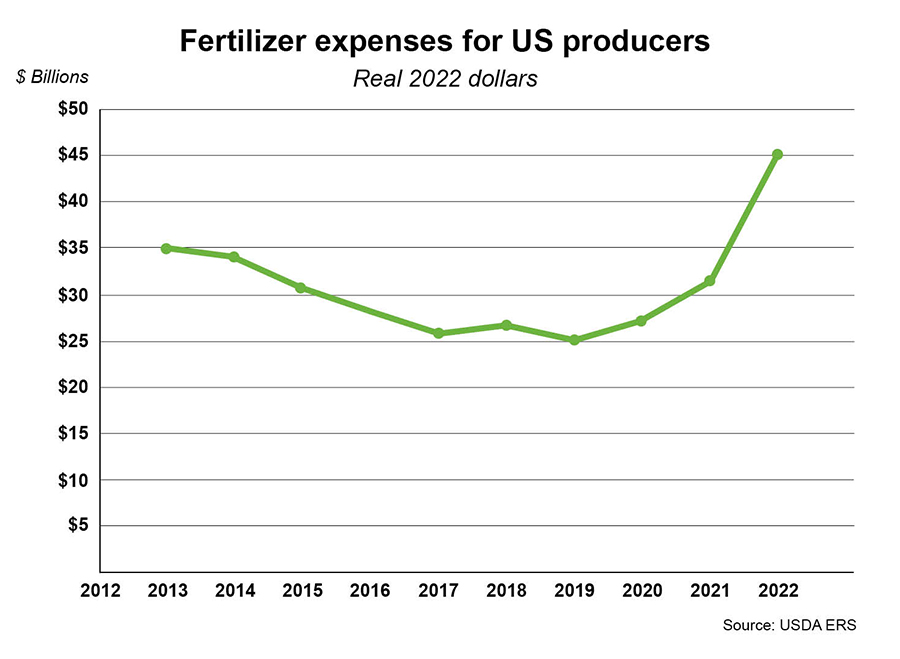

Farmers around the globe are desperate for fertilizer, and the absence of Russian supplies on the market is increasing prices beyond what many can afford – if they can even find them.

“To ease the global food crisis, we now must urgently address the global fertilizer market crunch,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in a speech at the U.N. General Assembly in New York last week.

“This year, the world has enough food; the problem is distribution. But if the fertilizer market is not stabilized, next year’s problem might be food supply itself," he said. "We already have reports of farmers in West Africa and beyond cultivating fewer crops because of the price or lack of availability of fertilizers. It is essential to continue removing all remaining obstacles to the export of Russian fertilizers and their ingredients, including ammonia. These products are not subject to sanctions – and we will keep up our efforts to eliminate indirect effects.”

Alzbeta Klein, International Fertilizer Association

Grynspan and Abdullah are immersed in the efforts to get ammonia out of Russia, but both say the process is taking longer than they would like.

Alzbeta Klein, International Fertilizer Association

Grynspan and Abdullah are immersed in the efforts to get ammonia out of Russia, but both say the process is taking longer than they would like.

It’s a difficult situation, says Alzbeta Klein, CEO and director general of the Paris-based International Fertilizer Association.

Russia accounts for 25% of the global ammonia market, but much of it is shipped out through a pipeline that runs from Samara, Russia, to the Yuzhny port in Ukraine. Yuzhny, Odesa and Chernomorsk are the three Ukrainian ports that were freed to export under the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse!

Before the war, Russia would send ammonia through the pipeline to Yuzhny, where it would be transferred to tanker ships and exported around the world, but the pipeline was shut down after the invasion began.

Abdullah told reporters last week that the technical procedures are in place for that pipeline to be reactivated and the port has the ability and capacity to get the Russian ammonia onto ships, but he also said there is no deal in place yet to allow it to happen.

There’s still “quite a bit of negotiation that is needed,” he said, stressing it would be a matter of political will to get it done.

But the biggest disrupter to the availability of nitrogen fertilizer and the largest driver of price increases for farmers is the lack of natural gas flowing from Russia.

Europe is the largest producer of nitrogen fertilizer, says Klein, and about 70% of European capacity is now shut down due to a lack of gas coming from Russia. That has farmers paying record high prices, if they can find the fertilizer.

“There’s no surprise that European producers are shut down because gas is more expensive than the cost of the final product,” she said.

Meanwhile, Russia is also a major producer and exporter of potash and phosphates, and barriers in the EU are getting in the way of trade for those fertilizers. Russia is exporting to countries like Brazil, and some is even making it to the U.S., where the Biden administration continues to stress there are no sanctions.

The U.S. Treasury Department released a fact sheet on July 14 “to further clarify that the United States has not imposed sanctions on the production, manufacturing, sale, or transport of agricultural commodities (including fertilizer), agricultural equipment, or medicine relating to the Russian Federation … The United States strongly supports efforts by the United Nations to bring both Ukrainian and Russian grain to world markets and to reduce the impact of Russia’s unprovoked war on Ukraine on global food supplies and prices.”

The European Union’s “clarifications” on its sanctions have been evolving, and even though it says there are no barriers to Russian fertilizer, Klein says there is Russian fertilizer sitting at major European ports like the one in Amsterdam; European banks will not take money from the Russian companies that shipped the product.

While the EU technically lifted sanctions on Russian fertilizer, concerns remain rife in the European banking, insurance and shipping sectors about whether or not they can be involved.

Grynspan says U.N. officials are hurrying to educate the private sector and assure companies that they can participate.

“All those clarifications have been made,” she said, but stressed that there are “still doubts” about sanctions.

“The market showed a chilling effect from the private sector,” Grynspan said. “This is a process we are working on.”

But it’s also more complex than that. One of the European Commission’s clarifications published in July left sanctions on Russian fertilizers that are transitioning through European ports and destined for countries outside the EU.

That spurred an immediate and stern reaction from Putin, who slammed the EU for discrimination against the countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, according to an account from Interfax, the Russian news agency.

But subsequent European Commission clarifications – the latest released on Sept. 19 – reverse course to prevent sanctions from impacting “food and energy security of third countries around the globe, in particular of the least developed ones.”

Shipping, banking and maritime insurance companies are still struggling to understand the changing sanctions landscape, but U.N. officials say they recognize that time is running out to prevent catastrophe.

“Without action now, the global fertilizer shortage will quickly morph into a global food shortage,” Guterres said. “We need action across the board. Let’s have no illusions. We are in rough seas. A winter of global discontent is on the horizon.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.