The 29 wells Landon Friemel draws from to irrigate 5,000 acres of land have been slowly depleting over his years of farming in the Texas panhandle, increasingly limiting what his farm can produce.

Friemel, who depends on water from the Ogallala Aquifer to support his crops, now only has enough to support sorghum production on 1,000 acres of land.

“It seems like every other year we’re cutting our sprinklers down or we’re cutting our acres on what we’re going to plant,” Friemel told Agri-Pulse. “Without any help from Mother Nature, it’s getting really tough.”

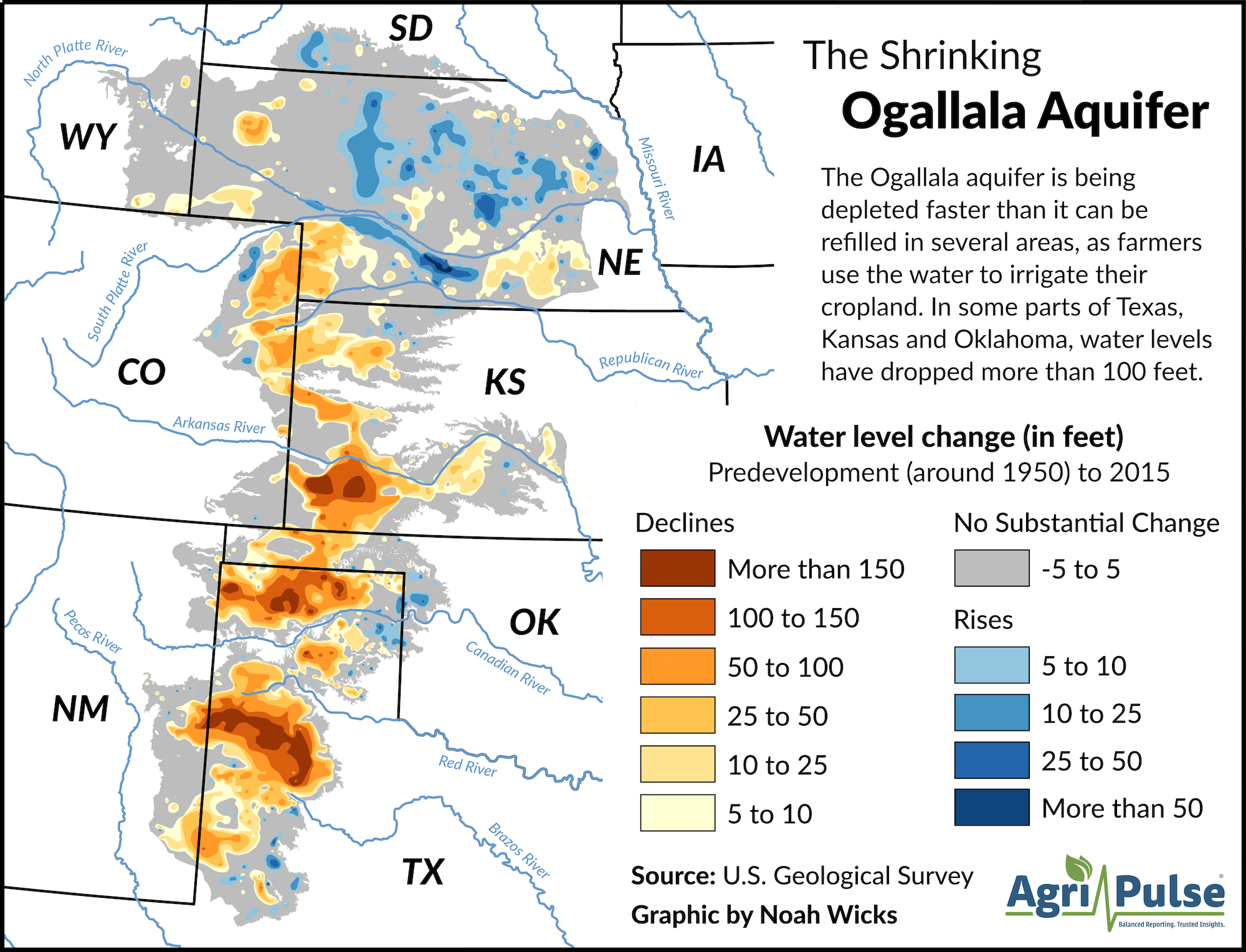

Farmers across southwestern Kansas, eastern New Mexico and the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles are facing similar problems, as they draw down the underground reserves they have long relied on to irrigate their corn, soybeans, cotton and wheat. Water levels have dropped more than 100 feet since 1950 in parts of these states, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In Kansas, the looming threat of depletion has sparked contentious state-level discussions over the future of the state's groundwater usage policies.

The Kansas Water Authority, a 13-member panel that advises the governor and state legislature on water-related issues, voted Dec. 14 to include language in its annual report calling for the state to end its policy of “planned depletion” of the aquifer and focus on actions to halt further declines.

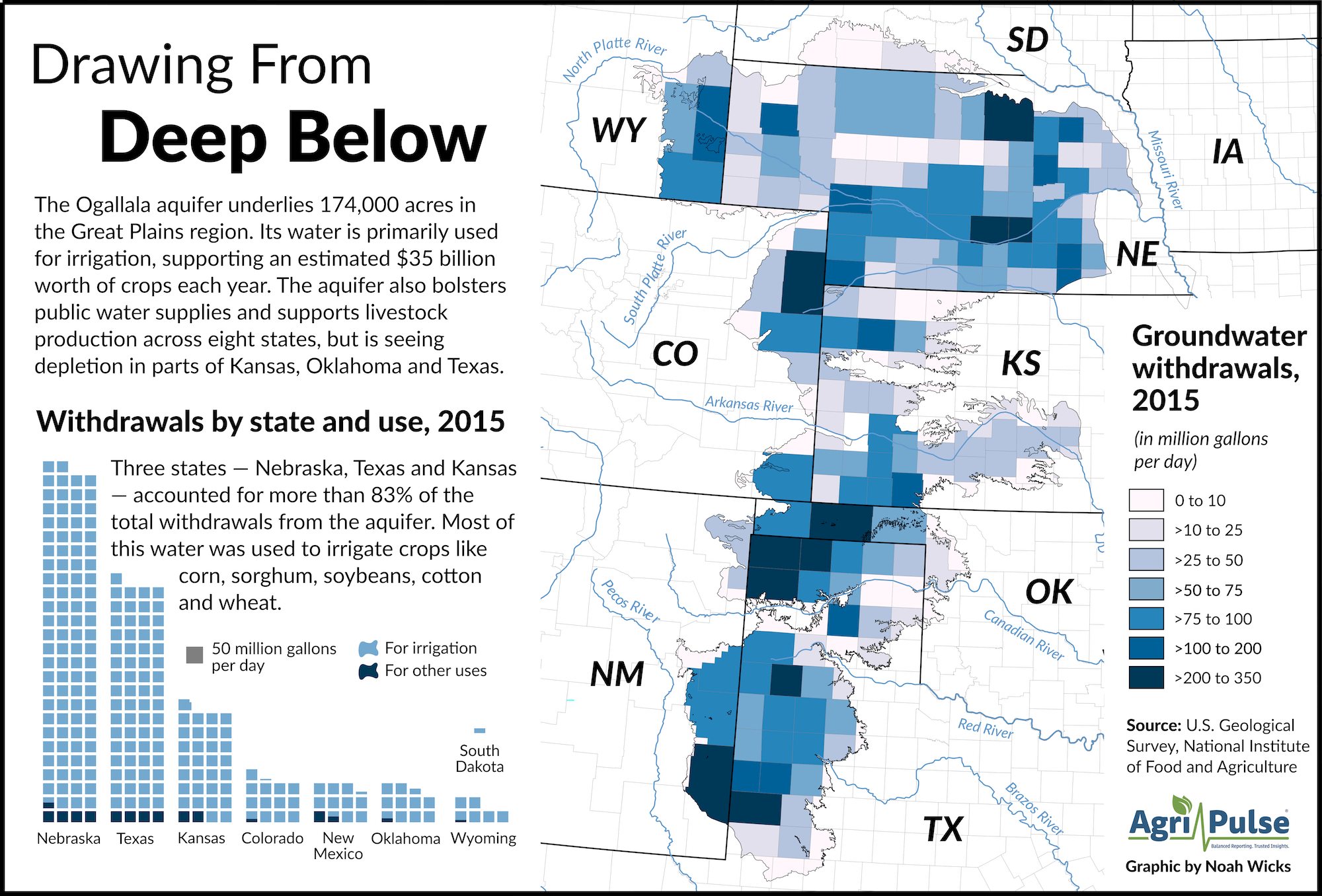

Stretching from the panhandle of Texas to the edge of South Dakota, the Ogallala Aquifer is the backbone of agriculture in the Great Plains. The expansive water source, called the High Plains aquifer by geologists, supports around $35 billion worth of crops a year, according to the Agriculture Department’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The most threatened parts of the aquifer recharge too slowly to combat declines, presenting farmers like Friemel with the challenge of figuring out how to keep their businesses afloat without being able to rely on consistent supplies of groundwater. They can expand their wells and draw from further down in the aquifer. But the deeper they dig, the more they risk entirely depleting their water supply.

“I always think we’re going to have water for livestock and domestic use,” Friemel said. “But irrigation? I have a bad feeling that it’s going to be gone in the next 15 to 20 years.”

Jay Kalbas, the Kansas state geologist and director of the Kansas Geological Survey, says the aquifer is going to be depleted “within a matter of decades” under current irrigation demands. The saturated thickness of the aquifer in Southwestern Kansas is estimated to decrease by 44 feet on average from 2015 to 2050, potentially resulting in losses of $2.2 million per year for the region’s agriculture-reliant economy, economists estimate.

“There’s a whole supply chain that got built up in part because of the access to the aquifer that might not have been there otherwise,” Nathan Hendricks, an economics professor at Kansas State University told Agri-Pulse.

The Kansas Water Authority is “trying to set in motion steps and mechanisms that will allow for agriculture and the economy of western Kansas to continue into the future,” Connie Owen, the director of the Kansas Water Office, told Agri-Pulse. “I find it to be a profoundly positive and important step that must be taken.”

Restrictions have already been introduced at the county level in three local groundwater management districts hoping to prevent further depletion in their regions. The Sheridan 6 Local Enhanced Management Area plan, or LEMA, which covers multiple counties in Northwestern Kansas, allots each producer 55 acre-inches of water for a five-year period to use as they would like, allowing them to pump more water in dry years and less in wet years.

A Michigan State University study of  the five-year plan found that it left enough water in the aquifer to provide over 1.4 years’ worth of historic water needs. Brett Oelke, a farmer who sits on Groundwater Management District No. 4’s Board of Directors, said the plan extended the life of the aquifer by 20 years.

the five-year plan found that it left enough water in the aquifer to provide over 1.4 years’ worth of historic water needs. Brett Oelke, a farmer who sits on Groundwater Management District No. 4’s Board of Directors, said the plan extended the life of the aquifer by 20 years.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse by clicking on our link!

“For the most part, we had actually stopped the decline of the aquifer,” Oelke said. “We had almost gotten the status quo just by reducing pumping by 20%, which was amazing.”

Other groundwater management districts have focused on setting restrictions based on how much water each farmer typically uses. Wichita County, for example, has adopted a LEMA plan that requires farmers to make a 25% reduction to their historical use.

Katie Durham, the manager of Western Kansas Groundwater Management District No. 1, said she believes LEMA plans provide a local approach to implementing restrictions. She said the plans can be tailored based on the needs of the region and what local water data shows.

“They create an opportunity for the community to decide on a conservation project rather than it coming from the state or federal level,” she said.

Greg Glover — who grows cotton, forage sorghum and wheat in Texas’s Deaf Smith and Palmer counties — said his water district has also established rules capping groundwater use at 18 inches per acre every year. While he thinks the rules are good, he said most farms in his area don’t have enough groundwater to come close to reaching the threshold.

“Most of our irrigation wells are just not capable of that anymore,” he said.

For more news, go to Agri-Pulse.com.