WASHINGTON, Aug. 30, 2017 – The Environmental Protection Agency is considering adopting new label language for dicamba herbicides to reduce the potential for soybean damage, estimated this season at more than 3 million acres throughout the South and Midwest.

EPA officials told state regulators and extension agents on a conference call last week that it is negotiating with Monsanto, BASF and DuPont – the makers of Xtendimax with VaporGrip Technology, Engenia and FeXapan – on the label restrictions.

Among the options: Designating the herbicides as restricted-use, which comes with recordkeeping requirements for certified applicators; requiring a cutoff date for application; and restricting application based on the temperature or time of day, or on the growth stage of the soybeans.

EPA officials also asked whether more education and training in use of the products would reduce potential for off-target movement of the herbicides.

Most of the state representatives who spoke, whether from the regulatory or extension side, said they didn’t see how training could address issues with the products’ volatility. They pointed to recent research showing that dicamba can remain volatile, and thus subject to movement, for days after application.

But they also pushed for a decision to be made quickly, given that growers need to decide soon on seed choices for next year.

Asked to comment publicly on EPA’s plans, the agency issued a brief statement: “We are continuing the dialogue with the states regarding how to address the off-target movement of dicamba.”

Monsanto, which estimates that its dicamba-resistant Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans have been planted on 20 million acres this year, says it is discussing the dicamba issues with EPA.

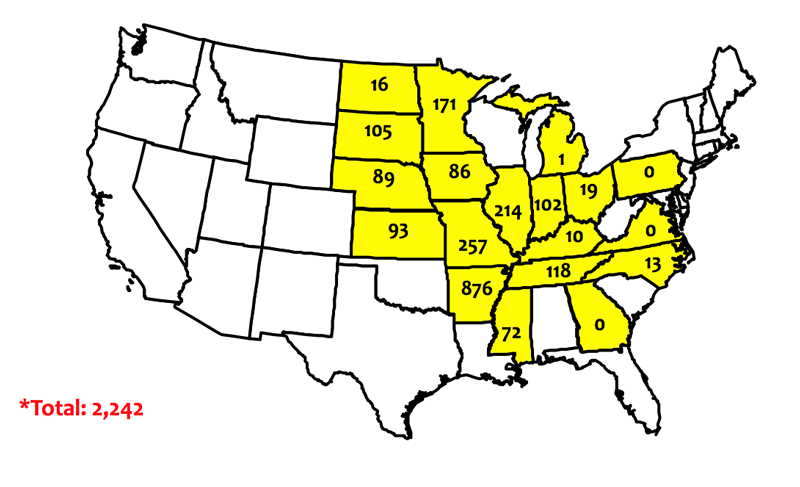

Official dicamba-related injury investigations as reported by state departments of agriculture (as of August 10, 2017) and compiled by Univ. of Missouri’s Integrated Pest Management.

“I wouldn’t call it negotiating,” said Scott Partridge, vice president of global strategy for the company. “Industry is working with EPA to have a fulsome understanding of what’s happening in the field.”

And BASF spokesperson Odessa Hines said the company will continue to cooperate with EPA “on developing fact- and science-based recommendations that focus on a long-term solution for farmers. We believe that weed control technologies that feature different modes of action can and must successfully coexist.”

Monsanto Chief Technology Officer Robb Fraley announced at the Farm Progress Show in Decatur, Ill., Tuesday that the company plans to have enough Xtend soybeans to cover half the nation’s soybean acres next season and said the “overwhelming majority” of farmers using Xtendimax have had “tremendous success.” USDA estimates that 89.5 million acres of soybeans were planted this year.

The issue has been the talk of agriculture this growing season, as damage or misuse complaints among growers and agribusinesses mounted and arguments about the technology and application have become more pointed.

Questions abound: Was their enough in-field research prior to commercialization? Was there enough applicator education? Were there some farmers who just cut corners to save costs – at the expense of their neighbors?

“I’ve never seen so much infighting within the (ag) family,” one source told Agri-Pulse. “And there is no easy solution in sight.”

Dicamba’s inherently volatile nature is at the center of the debate. Although the newer formulations are much less volatile than their predecessors, “less volatile does not mean not volatile,” as weed scientist Kevin Bradley at the University of Missouri has written.

Damage caused by off-target movement manifests itself in curled – or “cupped” – soybean leaves, but whether those outward signs will translate into significant yield losses won’t be known until harvest. Partridge said “a small amount of product can move off-target and produce symptoms of cupping, but plants grow out of it.”

Tests conducted by Bradley “indicate that we can detect dicamba in the air following an application of Engenia or XtendiMax/Fexapan for as many as three or four days following the application,” he wrote on the university’s website. “University weed scientists in surrounding states are seeing similar results in their research.”

In Arkansas, which has the most acreage affected (900,000 acres) and the most complaints (950 as of Aug. 23), tests by weed scientists have found that although the new formulations are less volatile than older formulations Banvel and Clarity, they do not behave so differently in the field.

“When you look at the new formulations in a field setting where volatility measurements are based on soybean injury, differences in volatility between older dicamba products such as Clarity and newer ones including Engenia and Xtendimax are not as evident,” University of Arkansas weed scientist Tom Barber said following a field day earlier this month.

“Although the new formulations are reduced in the amount of volatility that you can see, they’re not zero,” he said. “And we don’t know the level of volatility that’s required to injure soybeans. Soybeans are so sensitive, very, very low levels of volatility can cause injury.”

Arkansas, which only approved Engenia for use this year, is considering a cutoff date of April 15 for applications, which would amount to a ban since most crops in the state are planted after that date. A dicamba task force that met Aug. 24 made the recommendation to the state’s Plant Board.

Partridge said Xtendimax is “low volatility; it’s not no-volatility,” but Monsanto does not believe volatility is the problem. In a statement, the company emphasized that “nothing we have uncovered so far in these inquiries leads us to believe that these issues are due to inherent volatility of XtendiMax with VaporGrip technology. This is consistent with our findings through over 1,200 laboratory and field studies.”

“In the vast majority of the customer inquiries that we have investigated to date, the issues identified can be addressed through training and education,” the company said, noting that in 77 percent (736 of 957) of the cases it has looked at so far, “applicators have self-reported that one or more of the first seven of 10 key label requirements we are examining were not followed and could have contributed to off-target movement.”

“For the remaining cases, we are still evaluating additional key label requirements, including checking for sensitive crops downwind, and evaluating environmental and weather data,” Monsanto said. “Tank contamination, and proximity to fields where unapproved products may have been utilized could also be factors in some instances.”

University researchers, however, say the uniform nature of much of the damage they’ve seen can only be explained through volatility. And while improper cleaning of sprayers and tank contamination is certainly a factor in some of the damage, Bradley says, “Many growers with injured soybean fields didn’t even plant any Xtend soybeans or spray a dicamba product through their sprayers.”

Partridge said the top three areas where applicators did not follow label directions were in failing to have adequate buffers, using the wrong nozzles, and having an incorrect boom height.

Cupping of young trifoliolate soybean leaves following exposure to dicamba. Source: Univ. of Illinois IPM

The label itself has come in for questioning. A lawsuit filed last month in Missouri cited criticism of the Xtendimax label as too complicated, quoting University of Tennessee weed scientist Larry Steckel’s observation that “it is extremely hard to follow the label. The best example of this is that you cannot spray when the wind is above 10 mph or below 3 mph. Just that stipulation when you have crops to spray timely in three different counties makes the logistics a nightmare.”

Yet, Monsanto says it is “simply not true” that the label is confusing.

“The XtendiMax label includes clear instructions, which is why an overwhelming majority of our customers are having success with the product this season,” the company said.

The problems with dicamba come at a time when virtually all agree that new tools are needed to deal with glyphosate-resistant weeds such as pigweed, waterhemp and marestail. One weed scientist told Agri-Pulse, “I don’t know of a single weed scientist in the U.S. that would not want to see this technology be successful. We need this technology.”

“We’ve got a serious problem in the mid-south with pigweed resistant to RoundUp,” former longtime Missouri Farm Bureau President (and former Missouri Department of Agriculture Director) Charlie Kruse said in an interview. “It’s so critically important for everybody to use the product the right way.”

Kruse said that this season he saw some farmers planting Xtend soybeans “defensively,” using the seed even though they didn’t plan to use the accompanying herbicide. “They’re doing this to protect themselves from other people using dicamba,” he says.

“My hope is all this can be worked out and people can use it in a safe and appropriate way,” he said.