With 95 percent of California’s Central Valley wetlands lost over the last century to urbanization and other land use changes, researchers warn that the area’s once prolific native salmon could disappear within 50 years.

In response, rice farmers are trying to reverse that trend and help salmon populations recover. The California rice industry launched its three-year Ricelands Salmon Project last fall. Working closely with conservation groups like CalTrout and building on 40 years of UC Davis salmon research, the California Rice Commission that represents the state’s rice growers and millers aims to establish whether former wetlands now separated from the area’s rivers can be used to reinvigorate the salmon population.

Along with salmon recovery, the project’s sponsors hope their wetlands work will provide widespread benefits to include helping:

- Improve the flow of clean water to cities;

- Reduce flood threats to cities;

- Recharge aquifers;

- Revive the salmon industry along with its jobs

- Provide a model for resolving agriculture vs environment issues coast to coast and around the world, and;

- Calm California’s long-running water battles that often have led to bitter lawsuits between environmentalists and farmers.

It’s not a cheap or easy effort for farmers and more research is needed. But past research indicates dramatically higher growth rates and survival for salmon raised on winter-flooded rice fields. Confirmation could lead to cost-shared winter-flooding for as many as 100,000 of the Central Valley’s half million acres of rice.

A second part of the project is studying winter-flooding for perhaps another 300,000 acres specifically to have rice stubble decomposition create algae to trigger an explosion of the tiny insects that become ideal fish food. Ever since California banned the traditional practice of burning rice straw to clear fields, winter flooding has become standard. So it’s relatively easy, at an added cost of about $45 per acre, to flood fields and then pump the nutrient-rich water into rivers about every three weeks to feed fish.

This added “fish food” practice would make up for the fact that most of the area’s former wetlands are now cut off from the river system and so can’t be used for feeding salmon directly in the field. With careful management and an extra farmworker to manage the gates, however, field-enriched floodwater could be pumped into the river system.

The next step for this project is validating past research by tracking implanted micro-transmitter data from each year’s juvenile salmon given a head-start in nutrient-rich rice fields. Tracking the salmon from the field to the Golden Gate on their way to the Pacific Ocean before they return to spawn will decide whether the effort is worth the added cost.

If tracking helps salmon recover significantly, then the final step will be to recommend specific practice standards for potential USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) cost-share payments to participating rice farmers. Practices could cover everything from floodwater depths to perhaps cutting temporary ditches in laser-leveled rice fields to provide the fish with cooler water and shelter from bird predation.

But as the rice growers and researchers we interviewed pointed out, the practices will need to be flexible. Project leaders learned that lesson this year when they carefully planned on holding floodwater depth at 16 to 18 inches. But exceptional rainfall left the researchers with some fields 7 feet under water, with most of their 30,000 research fish roaming the entire floodplain, not just the 38-acre research plot.

Paul Buttner, California Rice Commission

California Rice Commission Manager of Environmental Affairs Paul Buttner has plenty of reasons to expect the Commission’s salmon project to succeed. Although he’s had only a year to learn all about salmon, he’s had 18 years managing the California rice industry’s work with migrating birds. Today, the state’s rice fields provide food and habitat for some seven million ducks and geese migrating along the Pacific Flyway each year and for shorebirds nesting in the fields year around. Studies show California ricelands now supply over half of the nutritional requirements of wintering waterfowl in the Sacramento Valley.

Buttner hopes rice fields will deliver similar results for fish. Yet he knows it will take more work and more cost. He notes that birds spot suitable habitat from the air. Buttner says fish, however, need “plumbing” to get them through the dams, weirs and levees to reach the fields and then swim on to the Pacific.

Buttner explains it will take at least two more years of research to develop salmon-recovery practice standards. But he says this work is going ahead with lots of support. “My industry is very excited about environmental projects,” he says. “They want to be a part of creating something new that’s a great environmental story.” There’s also ample funding because the rice industry, including input suppliers, have matched NRCS’s $600,000 in annual funding.

Along with supporting an important environmental goal, Buttner explains “If salmon populations recover, that’s better for the long-term position of rice. Everyone needs water, the fish need water, the farmers need water and if the fish are struggling, it certainly can impact your ability to put water on the landscape.”

Roger Cornwell, general manager of River Garden Farms in Knights Landing, hopes someday all 5,000 rice acres on the 15,000-acre operation will be enrolled in an NRCS practice for pumping fish food into the river. That’s because most of his acreage is “on the dry side” of the levee, so not accessible for raising salmon in the fields. For now, he’s convinced the effort he’s put into working with researchers on potential practices will pay off not only in helping salmon recovery but in curbing federal regulations that restrict farming.

Roger Cornwell, River Garden Farms

“Having robust populations of salmon back in the Sacramento River will help loosen or ward off any new regulations affecting our water supplies,” Cornwell tells Agri-Pulse. “That’s the end goal. The more fish, the more water there is for everybody.”

Jon Munger, VP of operations at Montna Farms in Yuba City, is confident that rice farmers working with researchers “can come up with practices that will help benefit the fish, just like we have done for birds.” Clearly, he says, “just putting more water down the rivers is not working.” He sees the answer as reopening the floodplains to feed fish because “If we can have practices that help the fish population, the end result will include protecting our water rights as well.”

After investing his own “time money and management” to help salmon recovery, Munger concludes that it’s been a great investment because “Most of the fish work fits in the winter window where you’re holding a water crop, as opposed to a rice crop.” Looking ahead, he sees national payoffs because “As with bird practices, California tends to be the leader in rice and environmental issues, so I think that what’s developed here can definitely be carried out in other farming states across the U.S.”

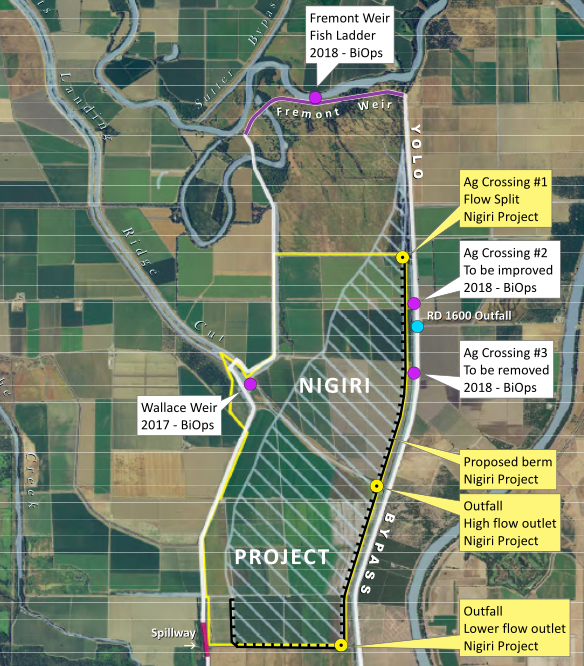

A closer look at the Nigiri floodplains project

California Trout Senior Scientist Jacob Katz tells Agri-Pulse that UC Davis began an intense focus on “floodplains being critical to aquatic ecosystems” in 2011, leading to the ongoing Nigiri Project that has confirmed the floodplains’ importance by “Mimicking natural flood patterns to restore floodplain habitat in the Yolo Bypass.” Katz explains the project today aims “to change the levee system, putting in operable gates, manage the floodplains, hold on to the water … to create a system that is managed like a winter wetland.”

Katz tells us these changes are needed because otherwise, “agriculture is always going to be embattled and is going to lose many of those battles” to the growing urban sector. He says that by re-engineering water systems to work with how natural ecosystems work, “instead of fish or farms, we can have both.”

Associate Professor Andrew Rypel, the Peter B. Moyle and California Trout Chair of Fish Ecology at UC Davis, says drastic declines throughout  California’s native fish species call for “big and bold” action such the Nigiri Project and the salmon recovery work that the Rice Commission, CalTrout and UC Davis launched last fall. He’s hopeful that this work will benefit not only California but also rice areas in states like Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas. Going beyond rice, he says there’s cropland in Illinois “that could be flooded in creative ways for sturgeon and other native fishes there.”

California’s native fish species call for “big and bold” action such the Nigiri Project and the salmon recovery work that the Rice Commission, CalTrout and UC Davis launched last fall. He’s hopeful that this work will benefit not only California but also rice areas in states like Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas. Going beyond rice, he says there’s cropland in Illinois “that could be flooded in creative ways for sturgeon and other native fishes there.”

Globally, Rypel is optimistic California’s salmon recovery work will provide a model to use in places like China, Australia, Korea, and elsewhere that face major challenges from “declining fish populations and declining freshwater ecosystem integrity.”

California’s salmon recovery work began over 40 years ago with Peter Moyle, now Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology and associate director of the Center for Watershed Sciences, UC Davis.

In an Agri-Pulse interview, Moyle explained climate change has increased pressure on salmon and therefore the urgency of rescue efforts. But he’s optimistic that successful winter feeding of salmon in Yolo Bypass rice fields will spread the practice to other areas.

Longer-term success, Moyle explains, will require major improvements for dams, weirs and levees to give wild salmon from the headwaters in the Sierras greater access to California’s reactivated floodplains. True recovery, he says, can’t happen until the floodplains once again host “mostly wild fish,” not the hatchery fish that researchers are forced to rely on for their current recovery work while river system obstacles remain in place.

Top photo: Anchoring juvenile salmon holding cages in deep floodwater covering Sacramento Valley rice fields along the Yolo Bypass

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.