Democratic presidential candidates looking to break through in rural areas are seeking advice on farm policy from activists, farmers, economists and organizations, and those ideas are popping up on the stump, in detailed policy proposals as well as in debates.

Earlier this summer, Beto O’Rourke made a pitch for making farmers a solution to climate change. The former Texas congressman said he wanted to “capture more carbon out of the air and keep more of it in the soil, paying farmers for the environmental services that they want to provide.”

The idea had its roots in Iowa, whose caucuses kick off the presidential primary season in February. A few days before that June debate, O’Rourke had toured a farm south of Des Moines run by Matt Russell, a fifth-generation farmer who runs a nonprofit called Iowa Interfaith Power and Light. Russell showed O’Rourke how farm practices such as longer crop rotations, conservation tillage and managed grazing could keep more carbon in the soil.

O’Rourke's one of several candidates who sought out Russell’s advice after seeing a March op-ed he co-authored with radio news director Bob Leonard in The New York Times headlined “What Democrats Need to Know to Win in Rural America.” O’Rourke brought up the issue of farmer carbon incentives at the first night of the initial Democratic debate, June 26.

On the second night of the debate, South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg did the same thing, and the issue also is featured prominently in a set of rural policies Buttigieg released on Tuesday.

Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg visits with Focus on Rural America Chair Patty Judge at the Iowa State Fair (Photo: Delaney Howell)

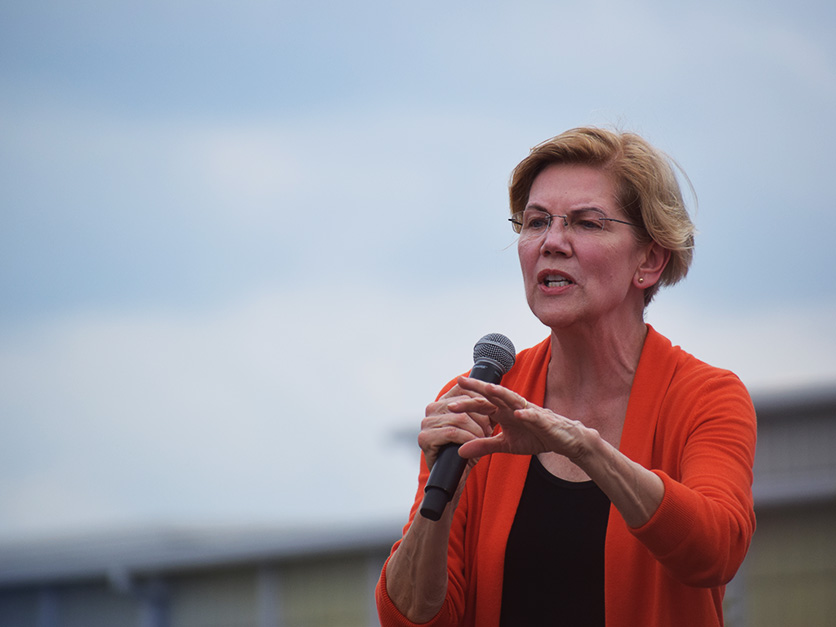

When Elizabeth Warren’s campaign was preparing a detailed farm policy plan, her team got advice from an economist at the University of Tennessee, home to a group of experts that have long advocated a return to supply management and a policy called “parity” that would guarantee farmers can cover their cost of production.

Sure enough, ahead of a campaign trip through Iowa last week, Warren (shown above) included the recommendations of economist Harwood Schaffer, who has proposed raising marketing loan rates and establishing a temporary land set-aside policy, similar to the Conservation Reserve Program, to reduce production. Under his plan, the loan rate for corn would nearly double from $2.20 to $4 a bushel.

Picking up on the ideas promoted by Russell and another organization being tapped by the candidates, the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, Warren’s plan also calls for supersizing the Conservation Stewardship Program to pay farmers for carbon-conserving practices. The program, now funded at $1 billion a year, would get $15 billion annually under her proposal.

No other major candidate has gone so far as to promote supply management other than Sen. Bernie Sanders, who mentions it briefly in his rural policy principles. But a common theme across the campaigns is the idea of offering farmers financial incentives to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a way of making the Green New Deal and other proposals to address climate change more palatable to rural voters.

The Democratic front-runner, former Vice President Joe Biden, released a rural plan in July that included a proposal to “make American agriculture first in the world to achieve net-zero emissions.”

The issue could be a challenging one for Democrats to deal with in rural areas. Many farm groups have long been wary of carbon regulations that would increase energy prices and farm input costs. Last week, after the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report recommended consumers shift toward plant-based meats, some Democratic candidates found themselves being questioned by reporters at the Iowa State Fair whether it was OK to eat meat.

Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan said it was an issue of “personal choice.”

“I’m eating less meat now but that’s a personal choice, and I think that sharing information with people is the right way to do that,” he said.

Russell is excited to see candidates talking about paying farmers to reduce carbon emissions, calling the campaign “a great opportunity to elevate that” issue. He and his husband also run a 110-acre farm about an hour south of Des Moines where they raise fresh produce, heirloom tomato plants and grass-finished beef.

“We’re not seeing just a moment in the campaign cycle that comes and goes. We’re seeing momentum,” Russell said. “We’re inviting farmers to be leading in this and we’re talking about creating the economic incentives to help them innovate to solve the problem."

Russell hosted California Sen. Kamala Harris, who is making a major push to win Iowa’s caucuses, for an hour and a half at the farm on Sunday, a day after she appeared at the Iowa State Fair. He also has talked to Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar.

Warren, meanwhile, released her rural plan last Wednesday and headed the next day to Harlan, Iowa, to a 700-acre farm run by Ron Rosmann, a prominent figure in sustainable ag circles, and his family.

On Friday night, Warren used her allotted five minutes of speaking time at the Iowa Democratic Party’s Wing Ding in Clear Lake, Iowa, to talk about the rural proposals.

Rosmann also pitched her on the idea of giving farmers more financial incentives to conserve soil carbon. Among other things, he showed her a field that had been recently planted to turnips, a cover crop that will be used for grazing.

Among Rosmann’s policy suggestions to her was to increase conservation compliance requirements for the federal crop insurance program, a proposal that would get significant opposition from conventional producers. “She said it was an interesting idea,” he said.

Sen. Kamala Harris flips pork chops at the Iowa State Fair.

But Rosmann said he also used the opportunity to push back on parts of the Green New Deal, reducing cattle production to lower methane emissions, and the Medicare for All plan, which would eliminate private health insurance. Eliminating cattle would make it harder for farmers to use rotational grazing to manage soil quality, and the idea of a single-payer health plan turns off rural voters, he warned her.

But all in all, he likes Warren. “I told her that most of her platform came out of the sustainable ag coalition, more or less. It sounded very similar and I’m all for it,” he said.

The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition as well as the National Farmers Union have had numerous contacts from campaigns seeking advice on farm and rural policy. Candidates who have contacted NSAC staff include Biden and Sens. Sanders, Michael Bennet of Colorado and Kirsten Gillibrand of New York. NFU staffers refer the candidates to a five-page set of policy principles.

The two groups aren’t quite in sync on the issue of supply management. NFU supports it and also calls for raising reference prices in the Price Loss Coverage. There is no mention of increasing loan rates. PLC, unlike the marketing the loan program, is based on a farmers’ historical production.

NSAC has supported supply management in the past but has a number of concerns about it now. The group, worries for example, that it could encourage more land use change in other parts of the world, potentially increasing carbon emission, and make it harder for new farmers to find acreage.

Schaffer, the Tennessee economist, told Agri-Pulse that he contacted several campaigns but that Warren's was the only one to show interest in a supply management plan.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.