Dean Foods, the country’s largest fluid milk processor, grabbed the attention of the American dairy industry this month when it filed for reorganization in U.S. bankruptcy court and announced a planned sale of operating assets to Dairy Farmers of America (DFA), the nation’s biggest dairy farmer cooperative.

The nearly century-old company has 58 plants coast to coast and distributes 88 trademarked dairy products. It reported $7.9 billion in sales last year. For consumers, the collapse may be no big whoop.

In California, the top dairy producing state, for example, Dean Foods products (Berkeley Farms, Altadena, and others) enjoy a major slice of the market. But, Geoff Vanden Heuvel, economic affairs director for California-based Milk Producers Council, says that with “this Chapter 11 reorganization, sale of the company, or whatever it ends up being … (Dean Foods') intent is to have it seamless from the consumer standpoint.” Its brands “have been around a long, long time, and I don’t think a change in corporate ownership really changes the public perception of those brands,” he says, “so I don’t think it matters” from a consumer perspective.

Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin, takes a similar view. The company secured $475 million this week in short-term operating cash, and he says “it appears Dean Foods will continue to … buy milk and pay for it (and) … consumers will see those same products in the store shelves.”

On the other hand, the failure of a mega processor is significant to the dairy industry. The company's declaration to the court spelled out reasons for its financial collapse. The company reported its costs for processing milk rose about 21% from 2013 to 2018 as its volume shrank by 4.2% overall in 2017, then 5.8% in 2018. The shrinkage was exacerbated this year when Walmart — its biggest customer, buying 15% of its production — curtailed that volume as it opened its own milk plant.

Dean Foods also reported trying “a series of well-intentioned cost-savings and strategic initiatives throughout 2018 and 2019 that fell short.”

But industry experts say its primary weakness has been its continued concentration in the fresh fluid dairy products arena. Three-fourths of its 2018 production was in milk and cream products, and another 15% was ice cream, its annual report says.

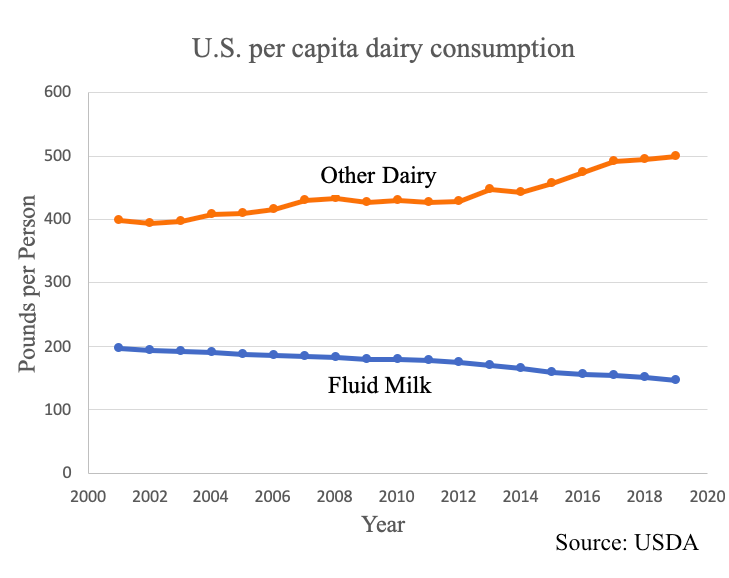

Meanwhile, nationwide, as the per capita volume of U.S. consumption and exports of dairy products is steadily growing, U.S. fluid milk consumption per person (see chart) fell 18% in 2008 through 2018, according to the latest USDA data. Ice cream consumption was down 10% in the same period.

Dean Foods' position is comparable to an automobile manufacturer who would stick to making only sedans (now just 23% of the U.S. vehicle market), while 65% of the American market has moved to SUVs, crossovers and pickups.

Stephenson says Dean Foods not only operates in a withering leg of the industry but milk processing is “a thin-margin business … (that has) declining consumption. That is almost a recipe for disaster.”

That’s the view, too, from Phil Plourd, president of Blimling and Associates, a Madison, Wis., a division of Dairy.com, who says, it would be “a mistake to extrapolate doomsday thinking” into Dean's troubles.

“While I think everybody would prefer that major processors don’t go bankrupt,” Plourd says, “there’s a lot more to the dairy industry than one large company that faced challenges with its business model, its asset mix — you know, its own challenges. Look, I mean dairy farming has never been easy,” he says, but “Dean Foods' bankruptcy is as much about Dean Foods as about anything else.”

International Dairy Foods Association President Michael Dykes, agrees. He says Dean Foods “is in the fluid milk business, and … dairy is so much more than just milk.”

Dykes points out that Americans’ per capita cheese consumption is breaking records (40 lbs. in 2018) and butter use is at a 50-year high. Plus, dairy manufacturers are diversifying with countless products and, for example, “we’re fractionating milk into different proteins and isolates, and they are going into products as ingredients,” he says.

So while the bankruptcy declaration points to the stampede of competing milk alternatives — almond, soy, oat, rice, coconut, hemp — and other beverages, Dykes points out that per capita dairy product consumption is up 6% from a decade ago, and “we’re seeing milk prices increase because we’re seeing demand for dairy products increase.”

The filing is, of course, “of intense interest to dairy farmers,” said Alan Bjerga, the National Milk Producers Federation senior vice president for communications.

He notes Dean Foods is “in advanced discussions” with DFA to determine which assets DFA will buy, “so it’s really hard at this point to make any blanket statement as far as impact on farmers.”

But, “clearly, whatever happens … there is one less buyer, which is Dean Foods,” Bjerga says, and he expects the impacts will spell “a lot of variety … based on what part of the country … the prevalence of processors, how much competition there is among cooperatives.”

Many independent dairy farmers who now sell to Dean Foods may have questions, he agreed, about their future market if DFA buys the plant were they now deliver milk.

But, Bjerga says, “the situation shows a lot about what the value of farmer-owned cooperatives really is. If you’ve got a co-op, you’ve got a buyer. The co-op’s got your back.”

Phil Plourd, Blimling and Associates

Plourd expects, with a farmer co-op that markets perhaps a third of U.S. milk production wanting to buy up such a big milk processor, that “regulators will have to take a look at how the various assets are arrayed and make sure that, whatever the rules or laws of competition … (they) are maintained.”

But, “first of all, DFA is a farmer-owned cooperative. Presumably, that means something,” he says. That is, “if certain of the assets do go to DFA, they’re moving into farmer-owned hands."

Stephenson, too, expects there will be concerns about monopoly control. “We’ve already had lawsuits brought against both of them (Dean Foods and DFA) on the East Coast because it was difficult for independent farmers to find other access to the fluid (milk) markets,” he said.

However, he believes excessive concentration in the industry “is not as big of a concern under this (situation),” considering what Dean Foods and DFA “are doing in this part of the supply chain.” DFA farms are Dean Foods' biggest milk suppliers. However, although DFA runs some dairy product plants, it’s not a big processor or distributor of milk and cream, as is Dean Foods.

Stephenson opines, “DFA probably sees this as, ‘we’ve been the sole supplier (to Dean Foods) in many regions of the country, for many of their plants, and we want to continue to (be) that supplier.’” So for DFA, he says, “It’s as much about retaining the sales opportunity to the fluid (processing) sector as anything else.”

For Plourd, the Dean Foods failure is another example of industry pain in adapting to consumers’ evolving tastes.

But, he says, “I think what’s a little jarring is the pace of innovation and change seems to be quickening,” and “I think there’s a lot more (change) out there. It’s noisy and it’s fast, but it’s all part of a long, unfolding story … even if it’s not with the same product mix it had five, 10, or 20 years ago.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.