State officials are increasing pressure on Californians to further reduce water use as they run up against barriers in a water system that has lost flexibility for adapting to scarcity over the last two decades. Farmers, water districts and residents have already cut back significantly on water use, while environmental protections for endangered species have led to rigid rules for water management.

“We don't have the flex in the system that we did when we had droughts in the ‘90s or even in the last drought,” Department of Water Resources (DWR) Director Karla Nemeth told reporters last week. “Some of that reduction has carried forward into permanent. So everything left on the table takes a little more oomph, a little more preplanning.”

CDFA Secretary Karen Ross acknowledged the considerable strides agriculture has made in water use efficiency over the decades. Growers have reduced farm water use by 14% while increasing productivity by 38% since 1980, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. The state altogether has maintained a 17% reduction in water use since then-Gov. Jerry Brown mandated a 25% reduction during the last drought.

Gov. Gavin Newsom in July asked Californians to voluntarily reduce water use by another 15%. Early data has shown urban water districts were slow to respond, raising concerns a statewide mandate could be next. Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said the administration will be closely watching voluntary efforts over the coming months but will take further steps if needed.

“The governor has been clear that we need to consider additional actions,” said Crowfoot. “Mandatory restrictions need to be on the table, if and when the drought worsens.”

State Water Resources Control Board Chair Joaquin Esquivel added that any mandatory order would be a stress test for how far the existing conservation efforts have come. Out of California’s nearly 3,000 water agencies, about 400 manage water for urban needs and have created drought contingency plans aimed at stretching supplies and conservation efforts across a five-year drought.

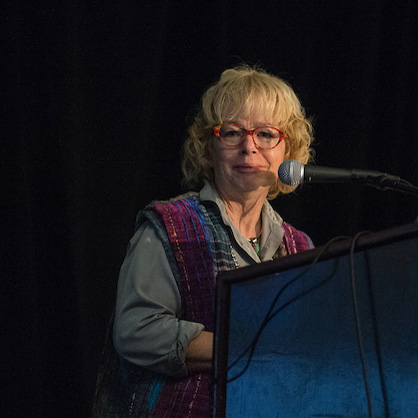

Jeanine Jones, DWR interstate resources manager

Jeanine Jones, DWR interstate resources manager

“If we were looking at mandatory, we'd really just be accelerating much of the outcome- and data-specific work that we're already doing with our water agencies,” said Esquivel.

Crowfoot explained that the administration has avoided a statewide mandate because the last drought showed that each region faces scarcity differently. In a similar approach to the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) and the state’s investment in water infrastructure, the administration stepped into a support role and is following the leadership of local agencies.

“[Water agencies] have explained to us that one-size-fits-all mandates from Sacramento sometimes have unintended consequences,” said Crowfoot. “Our focus has been: How do we support these water agencies to actually weather through this drought?”

The governor declared drought emergencies by watershed, rather than as a statewide emergency—against the requests of state agriculture committee chairs and other lawmakers. All but eight urban counties, nevertheless, have fallen under emergency declarations.

Crowfoot also explained that the implementation of SGMA is creating a new dynamic for this drought, with 250 local groundwater agencies launched following the act’s passage in 2014.

“We've got much better reporting on both the status of groundwater aquifers and use across our communities,” he said.

This year was also the first time the state has seen 22% of the projected snowpack disappear on the journey to reservoirs and the first time the snowpack dropped from 70% to nearly zero within six weeks. It also broke expectations in terms of statewide impacts.

“This is the first drought where we've had such an extensive landscape impacted by the drought conditions,” said Ross. “So the curtailment process has been especially painful this year. It came late in the year, when many of our annual crops were already in the ground. People were just trying to finish out the crops that they have.”

Assuming the drought continues, the preplanning will be critical next year, she explained.

“While it would come with great economic impact, we can prevent crops from going into the ground,” she said, adding that the water would be used in alternative ways.

This has been one of the biggest lessons the state has learned from the drought. Limiting allocations earlier in the water year and maintaining curtailments longer into the spring will largely affect growers with senior water rights, according to Nemeth. Her department is collaborating with the Bureau of Reclamation to establish an earlier and more intensive schedule through June for the federal Central Valley Project (CVP) as well, she said.

Part of that collaboration includes resolving differences between state and federal operations for pumping water through the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. In 2019 the federal and state administrations parted ways on pumping operations for the first time in history. Then-President Donald Trump approved new biological opinions that offered more flexibility with environmental flows for endangered species protections. The Newsom administration then filed a lawsuit against the environmental review and eventually the state approved a new incidental take permit for the State Water Project that volunteered more flows for the Delta to compensate for any reductions on the federal side.

With President Joe Biden in office, the agencies have been looking to return balance to the system under a single, coordinated approach. In a letter to wildlife directors last week, Bureau of Reclamation Regional Director Ernest Conant pledged to reexamine the biological opinions and outlined goals for protecting species, supporting operational flexibility and providing regulatory certainty. While the new plan would likely not affect pumping operations in 2021, a unified system would offer the state more options for protecting the environment in dry water years.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse West

At the Colorado River end of water deliveries, the Newsom administration is allocating $220 million over three years to restore the Salton Sea. This has been a sticking point in negotiations over drought contingency plans for the river. In 2019 Imperial Irrigation District (IID) demanded the state follow through on funding commitments for the restoration work after the Salton Sea fell into an ecological crisis when farmers reduced irrigation, leading to little freshwater runoff into the basin. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California volunteered to contribute IID’s share of cuts to Colorado River allocations to move the temporary drought contingency plan forward, which led to a lengthy court battle between the two agencies.

Last month the two parties settled the legal dispute, setting the stage for negotiations to continue for a drought plan that extends beyond 2026 and for more immediate actions next year. While Arizona farmers are suffering severe cutbacks in allocations due to the drought in the West, California farmers stand to take a hit next year.

“The Colorado River Basin obviously is in a world of hurt regarding water supply,” said Crowfoot.

Esquivel added that he was heartened to see the agreement between the two districts and that shows the other basin states that California is serious about its obligations, including stabilizing the Salton Sea and efforts to bring more water recycling and resiliency to Southern California.

“It's not lost on us that it's not just our Delta up here that is challenged but also the Colorado River Delta,” he said.

Jeanine Jones, who represents DWR for Colorado River affairs, shared that discussions are already underway for how the states and other stakeholders can more quickly respond to the evolving crisis.

“With respect to the immediacy of what we learned in the last drought in California, we're seeing the same kind of lessons on the Colorado River system, with drought impacts being much worse than were expected back at the time the existing guidelines were negotiated,” said Jones.

As a more immediate response to both droughts, the Newsom administration has been expanding efforts to persuade Californians to save more water, especially when it comes to lawn irrigation and other outdoor uses.

“Save the Drop, Angelenos—we need your drought leadership once again,” tweeted Crowfoot from Los Angeles last week, with a photo next to a water conservation mascot known as the Drop.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com