Interest, but also concern, is rising over three pipelines planned for the Midwest to capture carbon from ethanol plants and sequester it, which advocates for the projects say is a crucial step for meeting climate change goals.

But farmers in Iowa and other states are raising questions about the projects, particularly the first two which have announced more details.

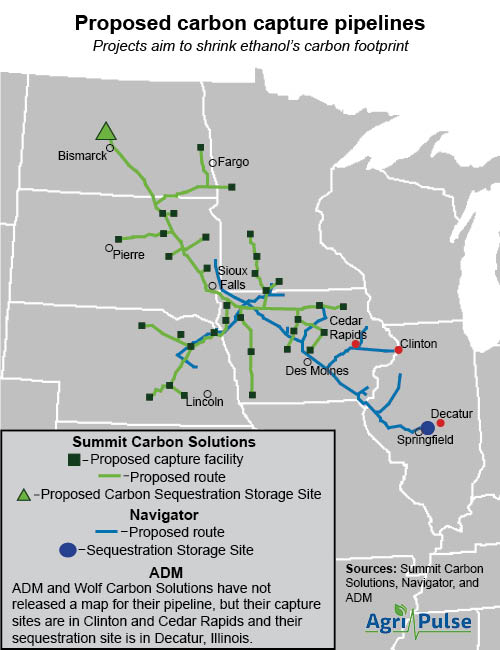

The initial project proposed by Summit Carbon Solutions' Midwest Carbon Express would affect about 3,000 parcels in the state, according to the company. The other two are Navigator CO2 Ventures’ Heartland Greenway pipeline, which is backed by Valero Energy and BlackRock Real Assets, and a newly announced project by ADM and Wolf Carbon Solutions.

“We're signing miles and miles of easements each and every day across the project in the state of Iowa,” Chris Hill, Summit’s director of environmental and permitting, told Agri-Pulse. “We're making really good progress on our right of way acquisition.”

The $4.5 billion project is planned to include about 2,000 miles of pipeline in Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota, with the sequestration site — where liquid CO2 will be injected underground — in North Dakota.

Navigator’s approximately $2 billion project would stretch 1,200 miles across Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota and Illinois, with sequestration taking place in Illinois.

The ADM/Wolf project “will offer dedicated capacity to transport CO2 from ADM's ethanol and cogeneration facilities in Clinton and Cedar Rapids to be stored permanently underground at ADM's fully permitted and already-operational sequestration site in Decatur, Illinois,” the companies said, adding the 350-mile pipeline “would have significant spare capacity to serve other third-party customers looking to decarbonize across the Midwest and Ohio River Valley.” No specific route has been identified yet.

Summit’s project is the furthest along. The company has held 40 informational meetings across the footprint of the project and hopes to begin construction in the first quarter of 2023 and complete the project in 2024.

Summit’s leadership includes Bruce Rastetter, CEO of Summit Agricultural Group and a major Republican donor. The company also boasts as senior policy adviser former Iowa governor and ambassador to China Terry Branstad. And in November, Summit brought on Jess Vilsack, Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack’s son, as general counsel.

A USDA spokesperson told Agri-Pulse that the secretary received guidance from the department’s ethics office “that he would need to recuse himself from specific party matters (such as contracts or cooperative grants) that the company may seek with USDA.” That still leaves Vilsack free to engage in “broad government policy matters” affecting ethanol and carbon capture.

Landowners in the path of both Summit and Navigator are concerned about long-term yield losses, which some growers experienced after the construction of the Dakota Access crude oil pipeline. An Iowa State study released in November found "significant soil compaction and gradual recovery of crop yield in the right of way over five years."

About a dozen landowners fought Dakota Access all the way to the Iowa Supreme Court, which ruled against them in finding that the pipeline qualified as a “common carrier” that allowed it to exercise eminent domain. (Both Summit and Navigator say their strategy is to get landowners to sign on voluntarily.)

But when Dakota Access was in the works, landowners were not united, said Jess Mazour, conservation program coordinator at the Iowa Chapter of the Sierra Club.

“There were a lot of people that were against it,” she said. “But they were working on their own, or they were working in a small group in their neighborhood, and there was not a lot of coordination and unity across the state.”

This time around, Mazour said the Sierra Club is getting a lot of calls from people who are worried about the impact on their land and livelihood. “We have to put up this strong fight right now to get people not to sign and we need to make sure that we can reach everyone,” she said.

“I couldn't tell you how many people I'm getting calls, even handwritten letters from just saying, ‘Thank you. I felt hopeless until I found the group.’”

At a public hearing before the Iowa Utilities Board on Jan. 18, dozens of landowners peppered Navigator representatives with questions and, in some cases, complaints about the project.

Summit’s Hill said the company’s goal is to attain all the necessary rights of way through the acquisition of voluntary easements and says “it's very clear that … most of the landowners want this.” Summit has signed up 31 ethanol plants as partners in the project, designed to capture more than 10 million tons of carbon dioxide annually that would be stored in North Dakota. (Navigator’s project, which would take CO2 from ethanol and fertilizer plants, would sequester up to 15 million tons annually in Illinois, and ADM and Wolf say its pipeline can transport 12 million tons.)

Summit is trying to make sure that opponents such as Sierra Club cannot find out which landowners in Iowa the company has contacted about its plans. The Iowa Utilities Board issued an order requiring Summit to release the names of businesses and government entities in the pipeline’s path, which Summit said would force it to release the names of most farmers.

The matter is in Polk County District Court, where a hearing has been set for Jan. 27.

Jan Norris, whose Red Oak, Iowa, property is about a mile from the proposed route, is organizing opposition against both Summit and Navigator. In some cases, landowners’ property is in the path of both the Summit and Navigator projects, said Norris, who also is a representative on the state Democratic Party's central committee.

She’s worried about safety, pointing to a 2020 rupture of a CO2 pipeline in Mississippi that sent more than 40 people to the hospital. But she also questions the market's ability to support three CCS projects. If the ethanol market tanks in the future, in part because of the adoption of electric vehicles, the state would still be left with the pipelines.

Hill said there are misconceptions about the Mississippi accident. The CO2 moving through that pipeline contained impurities that presented a risk to the integrity of the pipeline, he said. The company also says there have been no deaths involving CO2 pipelines in the U.S. in the last two decades.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

Asked whether the market currently can support multiple pipelines, Hill said, “When you look at the number of projects that are being announced, I think it's a great opportunity for the state of Iowa. … To me, it just shows that these are viable projects and economic projects.”

A spokesperson for Navigator’s Heartland Greenway project acknowledges “there is a lot of activity in this space. Competition provides options for the industry, allowing these plants to pick a commercial model that works best for them. It’s not just transportation fuels, nearly all sectors are looking for ways to reduce their carbon footprint, so we anticipate that interest in CCS projects will continue to grow.”

And a spokesperson for Wolf Carbon Solutions, which is partnering with ADM, said, “We believe three systems can coexist."

“The Midwest market is a massive land area with a significant number of large-emitting facilities critical to the U.S. economy,” the spokesperson said. “We especially like our position on the eastern side of the Midwest, giving us proximity to industrial facilities in the Chicago and St. Louis metro areas as well as the Ohio River Valley.”

Another criticism is that the projects might use sequestered CO2 for enhanced oil recovery. Hill flatly rejects that notion, despite comments from Rastetter in an interview last year suggesting that was being considered.

“There is no plan to utilize the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery,” Hill said. “Where we're injecting, there's no oil and gas development, there never has been, and that's part of the reason why we're selecting that area.” In addition, using the CO2 in that fashion “would actually reduce our revenue source.”

The Navigator spokesperson said the "project footprint will not coincide with any area where EOR is taking place. Navigator intends to focus on long-term storage and sequestration."

Wolf Carbon Solutions also said that for its project with ADM, “Wolf is currently focused on sequestration of all CO2 captured into the system.”

The companies are planning on taking advantage of the federal 45Q carbon capture tax credit of $50 per ton. Ethanol and other plants that emit CO2 also can lower their carbon intensity scores in order to engage in and receive revenue from low-carbon fuel markets.

But the lasting impacts of the pipeline are what worry some farmers in Iowa. Charlie McCracken, a corn and soybean farmer in Jefferson County, Iowa, says some of his land is still damaged from the Dakota Access pipeline.

“There’s not really any love toward doing this again and getting your farm torn up,” he said.

Nineteen counties have sent letters to the Iowa Utilities Board opposing the use of eminent domain for either the Summit or Navigator projects, or both, saying they would only benefit private companies. Linn County supervisors, for example, said in their letter that they’re concerned farmland will be permanently damaged.

“We are worried about the proper restoration of agricultural land following pipeline construction, interference with proper drainage, the effects of pipeline construction on long-term soil health, and possible other negative environmental impacts,” they said.

Another issue is landowners being pressured to grant easements. Norris and Mazour said they had heard from or about landowners who felt intimidated.

Hill acknowledged that there have been “incidences where we quickly heard about a land rep or a land agent conducting themselves in a less than professional manner.” Those people are immediately removed from the project, he said.

“I can say with complete certainty, the tone from the top … is aligned with making sure there's no intimidation, and that we have a long-term partnership with the landowners,” he said.

"The project’s land agents are trained to avoid any intimidating behavior, as that is not tolerated by the company," the Navigator spokesperson said.

Summit and Navigator say they’re offering compensation both for the easement and any damage associated with construction, along with payments for yield losses. Wolf is developing a compensation plan.

Summit, for example, says its “initial offer” for the 100-foot land easement will be 115% of fair market value. It also will pay for 100% of crop loss in the first year, 80% of crop loss in the second year and 60% in the third year. Hill said if after three years yield is still not back to where it was, “we will make it right.”

Navigator’s formula is similar, offering 100-80-60% yield loss compensation. “There are also payments associated with: 50-foot permanent easement for placement of the pipe, [and the] 50-75-foot temporary easement necessary for construction activities,” the Navigator spokesperson said.

“Should a landowner experience cumulative yield losses beyond the 240%, at any point throughout the life of the project, we will make that landowner whole,” the spokesperson said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.